With a whole world of rich craft traditions that many of us have not had the chance to know and enjoy, Mamaa Trade operates as a way to connect the businesses of craftspeople from Ghana, Uganda, Afghanistan, and Syria via e-commerce, as well as in local shops and markets in Ontario. I spoke with the owner, Johanna Helin, to see how it all began:

30 years or so ago, you worked in Africa with your grandfather when he donated water drilling machinery upon his retirement. What happened between this experience and establishing Mamaa Trade that prompted you to sell handcrafted goods when you moved to Canada?

My first trip to Africa was to northern Namibia, Owamboland; a place where Finnish missionaries had been working since 1870. It was an odd experience as the locals knew about Finland and were baptized with Finnish names. That trip sparked a long-lasting love for Africa. After coming back from Namibia, I changed my major at the University of Helsinki to anthropology and did my MA research with local market women in a small rural village in Guinea, West Africa.

After university, I lived and worked in Estonia, as well as in Ghana. Together with a group of Estonian friends, in 2007 we founded the first development NGO in Estonia, Mondo. My previous contacts helped us to establish Mondo's first development cooperation project with women's groups in Ghana. That was in 2009 and I'm still working with the same women now in Mamaa Trade, a social enterprise I founded after coming to Toronto in 2018.

Do you find that working with artisans empowers them to do more business in their own communities?

The main problem for the women I'm working with is poverty. They are really hardworking women, but at the local level they are not able to make ends meet. Many of the women are widows, single mothers, or have disabilities, so they are in a very volatile position and are the main providers for their children. School and healthcare are not for free, so the future of their children really depends on their opportunities to find income.

Some women are also selling in the local market. But the problem is that the prices are very low as the population is poor. Exporting is the main solution for getting a better price for their products. In northern Ghana there are also large businesses buying these products from the cooperatives, but the prices they are paying are very low. Fair trade practices are not common and the local producers are on the losing end. Our solution to raise people from poverty is to work on the quality of the products, pay a fair price to the producers, and export the goods to markets where people are willing to pay a price that does not exploit anyone.

What does the work of these craftspeople bring that stands apart from other goods?

Nowadays, more and more consumers want to know where and how the products they are using are made. The strength of my business is that I know the story behind the products. I can show customers a photo of the producer and tell her story. I'm also working with the women to ensure that the whole production process is sustainable. The shea makers are, at the same time, protecting the trees and planting more trees in an area that is suffering from deforestation. The weavers are trying out natural dyes. All the packaging is reduced as much as possible and is recyclable. But mainly, the strength is in the individual stories of the women, how the business has helped them to educate their children, get clean running water for their household, or generally have a brighter view of the future. Who would not want to be part of that?

“Mamaa” means “Fair” or “Equal” in the Nabit language of northern Ghana. Can you explain to us how the fair trade process works?

We have a long-term partnership with these women and want to see them benefit and prosper. Therefore, we are supporting them in many ways. Mondo sends volunteers to the communities. For example, there have been some Estonian designers who have helped the women to develop new models that fit better with European and North American tastes.

Together with the volunteers, I help in improving the quality of the products, take photos and videos that can be used for marketing, help in organizing the shipments, and build the capacity for the women to do all of this by themselves in the future. All the payments are also done in advance, to help the women to buy the shea nuts, straw, or fabrics they need for production. The price is calculated according to fair trade principles, so that it covers all of the costs of production and provides a living wage for the producers for the amount of time they have worked. We are not there yet, but when Mamaa Trade becomes profitable, we have also promised to invest a percentage back to the community.

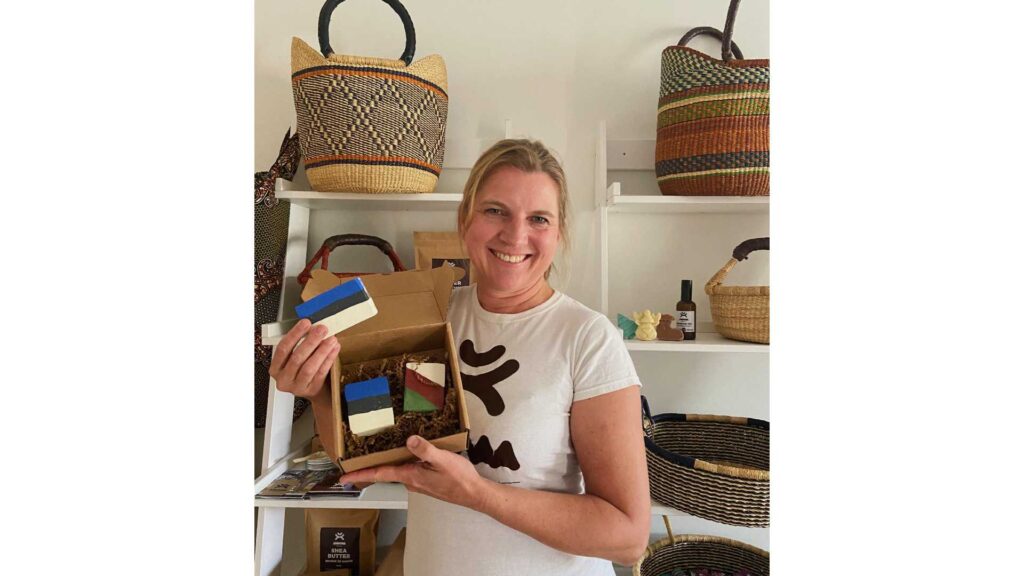

This Christmas season, you'll be selling sini-must-valge (blue, black, and white)coloured soap bars. Can you tell us more about these? When and where can we find them to purchase?

Through Mamaa and shea butter, I found the art of cold process soap making. Shea butter lasts very long if kept in the right conditions, but eventually it starts losing some of its beneficial vitamins. Processing shea butter into soap makes it last forever, and the soaps are really moisturizing, cleansing, and have a nice soft lather.

I've used the blue, black, and white combination for swirls and stripes. For Filiae Patria's 100th Anniversary, I made some white, red, and green soaps with lavender and lemongrass essential oils. For Christmas, I've now made decorative soaps with either spruce or cinnamon scents.

All Mamaa products can be found at www.mamaa.ca/shop and if anyone wants a custom order of soaps in their favourite colours, that can be organized by writing to johanna@mamaa.ca

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.