60 years after stem cells were first discovered, they continue to make quite a stir within the international medical community. This is due to the hope that stem cell treatments may regenerate the body and treat injuries and diseases with faster recovery times, but also due to the concern that they may create further health challenges for patients.

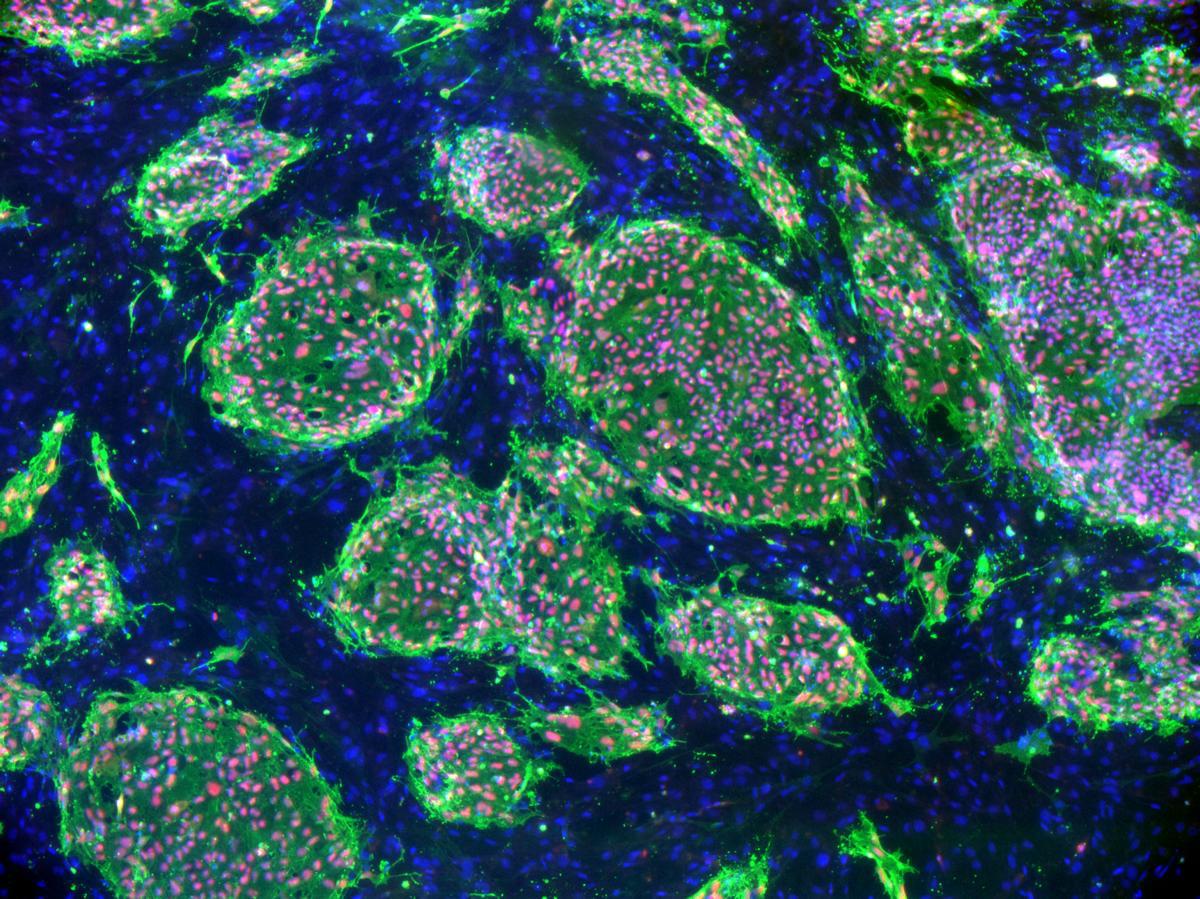

So how does stem cell therapy work? In simple terms, a stem cell is a cell that is not yet differentiated. It doesn't have a specific purpose, like a brain cell or blood cell. However, within the human body and under controlled laboratory conditions, stem cells can make copies of themselves, or make cells of a specific type.

Stem cells can be found in a few different places. A hematopoietic stem cell is a type of adult stem cell found in bone marrow, which can produce new blood cells. Umbilical cords may be donated after the birth of a child as a source of stem cells. They can be collected from human blood. It is also possible to take stem cells from embryos up to five days old that are unneeded after in vitro fertilization procedures.

For treatments, stem cells enter the body intravenously or are injected into parts of the body affected with disease or injury, to replace damaged cells.

Stem cells were discovered by two Canadians, the cellular biologist Ernest McCulloch and biophysicist James Till, at the University of Toronto in 1961. It was an accidental discovery, when bone marrow cells were injected into mice during research on the effects of radiation. By 1981, the embryonic stem cells of mice were grown for the first time in a lab. This moved on to human embryonic stem cells in 1998. Though, the use of stem cells in therapy actually predates their 1961 discovery — the first bone marrow transplant took place in the 50s. By 2012, one million stem cell transplants had been performed around the world.

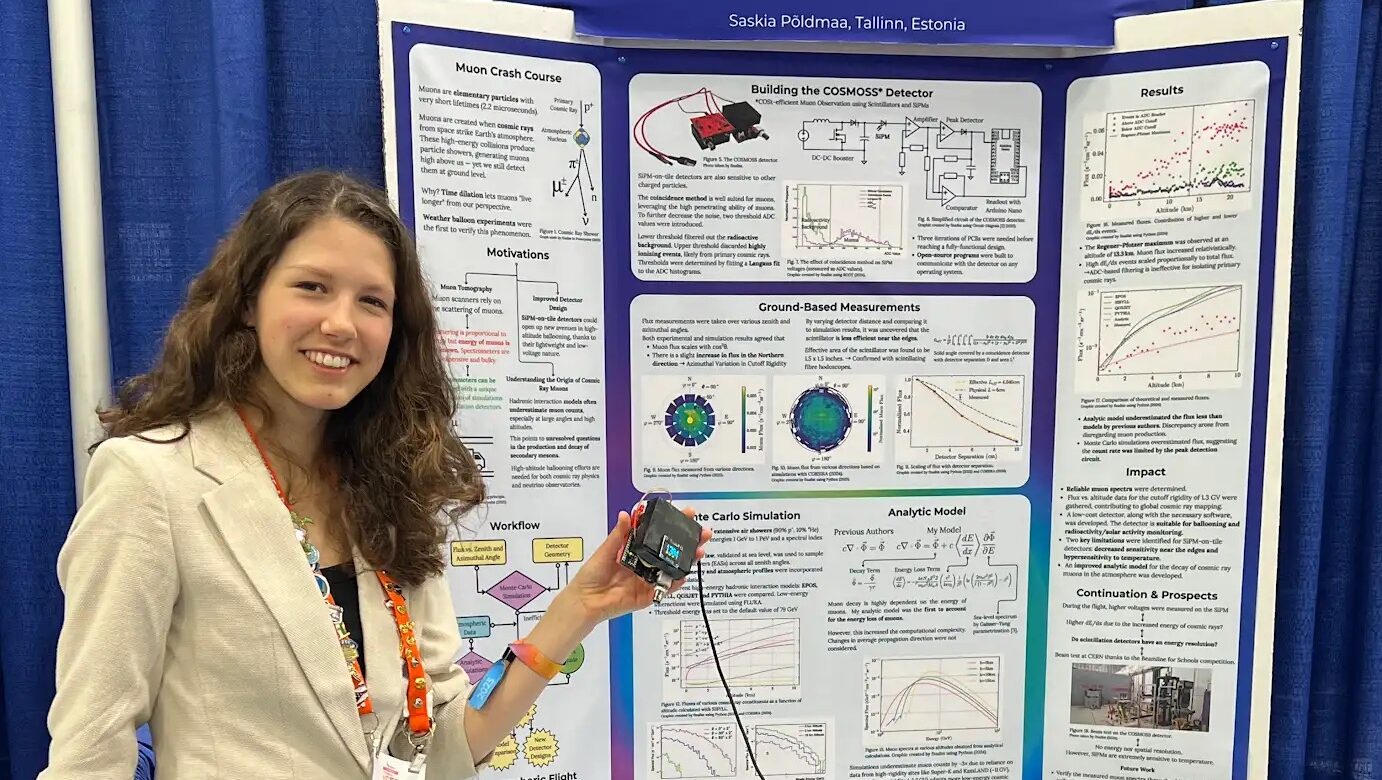

In Estonia, patients seeking stem cell treatment are able to go to the North Estonia Medical Centre in Tallinn. The Centre has noted that at their location, treatments are done with a patient's own stem cells, while at Tartu University Hospital, the therapy can be done with either one's own cells or donor cells. It was at this latter hospital that Estonia's first marrow transplant was done in 1993, followed by Estonia's first haematopoietic stem cell transplants in 1997.

As explained by Tiina Titma, a researcher at Tallinn University of Technology, in Estonia, “requirements relating to quality and safety for the procurement and handling of cells, tissues and organs… are regulated under the Procurement, Handling and Transplantation of Cells, Tissues and Organs Act.” Likewise, stem cell research is regulated so that consent is required from anyone donating cells, tissues, and organs. The high cost of treatments limits them from being sought out more widely, though.

In Canada, there has been caution surrounding stem cell therapy. Only three stem cell treatments have been approved in Canada, for Graft V Host Disease, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Adult B-cell Lymphoma.

In May 2019, Health Canada warned against unauthorized cell treatments offered by some clinics and health care practitioners. They advised that “Unauthorized treatments have not been proven to be safe or effective and may cause life threatening or life altering risks, such as serious infections.”

Health Canada asserts that “…most cell therapies are still experimental. This means that they may be administered to Canadians only if the health care practitioner is conducting a clinical trial authorized by Health Canada.” Authorized treatments and clinical trials are found on the Drug Product Database and Clinical Trials Database.

The eagerness for stem cell treatments grows, and patients in both Estonia and Canada have sought these types of treatments; but it will take increased clinical observation and research before a consensus can be reached in the medical community on the therapy's use.

While there is still much to understand within the field of stem cell research, it is clear that there are many remarkable possibilities we have yet to uncover after the initial discovery of stem cells 60 years ago.

Written by Vincent Teetsov, Toronto