After being born in Toronto in 1962, growing up in the city, and attending two universities there, I wondered if I would spend my whole life in Toronto. I have always liked Toronto, but the world is a bigger place. Estonia achieved its re-independence in 1991 and by that time, I had worked as a lawyer in downtown Toronto for four years. I saw going to work in Eesti for one year as a chance to break out of my Toronto rut. And the cause—of participating in the rebuilding of Soviet-occupied Estonia—seemed very worthwhile.

To be painfully honest, I was not that ideologically driven. Some of my friends spoke more of “returning to where they belonged, the land of their forefathers.” I had more of a sense of adventure when I decided I would work for one year in Estonian government ministries; and unless something unexpectedly great happened, I would return to Toronto.

The chaotic first year

And so it went. I worked in four government ministries throughout 1992. It was a crazy time, where Soviet ministries and state departments were reorganized or eliminated. A Soviet command economy was being transformed into a capitalistic society. It was a chaotic and exhilarating time. For the first half of 1992, the currency was still the Russian Rouble and the price of one's lunch in the ministry canteen rose every day, as inflation was 1076% in 1992 (as detailed by Statistics Estonia).

I am grateful for having had the opportunity to see this and live through it. I believe, for local Estonians, it was an extremely difficult period of time as no one was sure how this story would end. What if Estonian re-independence did not work? What made it psychologically easier for anyone with a foreign passport in their pocket was that if life became insane or unbearable, one could always leave.

It was during the turbulence of 1992 that I made a major decision in my life without quite recognizing its implications. I was working 10 hours a week at the Estonian Ministry of Justice during the fall of 1992. One day, the head of my department said that the Estonian Government had purchased Estonian passports and that all of us, employees at the Ministry of Justice, could apply for an Estonian passport. I was quite satisfied with my Canadian passport and had not considered obtaining a second citizenship. Between skyrocketing inflation, Russian mafia shootings in the streets, bombings, no European Union or NATO membership in sight, and more. Estonia was still a turbulent place. And yet, I duly submitted my application for an Estonian passport with the rest of the employees in my department. It's easy to think that accepting citizenship is a profound act, a comment about who you really are or what you feel inside, or where your true loyalties lie. Me? I just sort of fell into it.

It is easy to think that accepting citizenship is a profound act, a comment about who you really are or what you feel inside, or where your true loyalties lie. Me? I just sort of fell into it.

Applying for my passport

One of the funniest parts about my application was the need to prove that at least one, if not both, of my parents held Estonian citizenship during Estonia's first period of independence. Every applicant was required to submit this proof. Many applicants for citizenship spent significant time and money collecting proof from archives or churches to prove their Estonian ancestry. But as I had an Estonian name and my passport application was submitted with all the rest of the Ministry of Justice passport applications, nobody asked us for any supporting documents. I was never too worried, as both my parents were born during Estonia's first period of independence and my father still had his original Estonian passport.

Building a social network

Another subject that I have written about and wanted to comment on is making friends. During my first years in Estonia, the majority of my friends had not been born in Estonia. I felt more at ease with these people and it was easier to “click” with them. But the longer I stayed in Estonia, the majority of non-Estonians left Estonia. I had many very good friends from my time in Canada, but it didn't feel quite right that living in Estonia, I had so few Estonian friends. So I made a conscious decision, that although I may not feel that close to some Estonians, I needed to reach out and make an effort to make more Estonian friends. I have done that and I believe it has worked to my benefit in two ways.

The longer Estonia is no longer occupied by the Soviet Union or Russia, and the longer Estonia is a member of the European Union, the closer together Estonians and North Americans move in spirit. So I would argue that the “gap” between Estonians born in Estonia and Estonians born outside of Estonia has greatly narrowed. I feel this most strongly when I am among the grade 7 to grade 9 students that I teach. Would grade 7 and 8 students in Toronto be very different from the students I teach in a suburb of Tallinn? Admittedly, some differences will remain. As Robert Kagan wrote, “Americans are from Mars, Europeans from Venus.” And here I would place the Estonians firmly in Venus' bosom.

The other side of the coin is that as I have tried harder to make friends with Estonians, the more friends I have made. I would add that my Estonian friends have, in general, attended university abroad, lived abroad, or worked for foreign companies in Estonia. That has probably meant that their exposure to non-Estonian has made it easier for them to accept me as a friend.

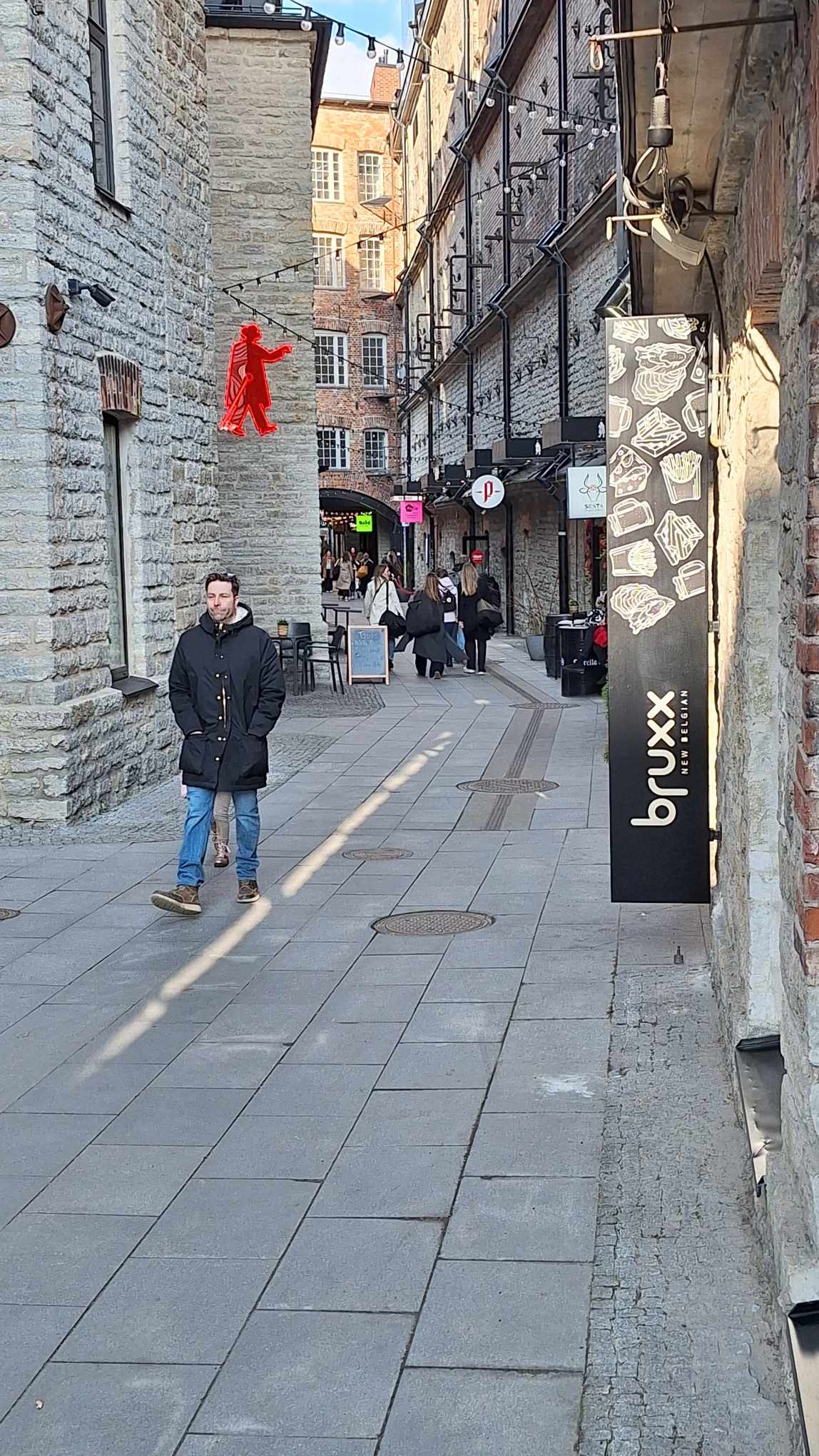

If someone had asked me in the early 1990s if I had moved permanently to Estonia or if I planned to live here for the rest of my life, I would have answered “Certainly not.” But life is funny. There was no one point where I said “I have decided to live here”, but over time, you build a life you like and are happy with. And then why leave?

But somewhere, in the first half of the 2000s, I realized that I was living here permanently. I was comfortable with the idea that Estonia was my home and what that entailed. And it is a view I hold to this day.