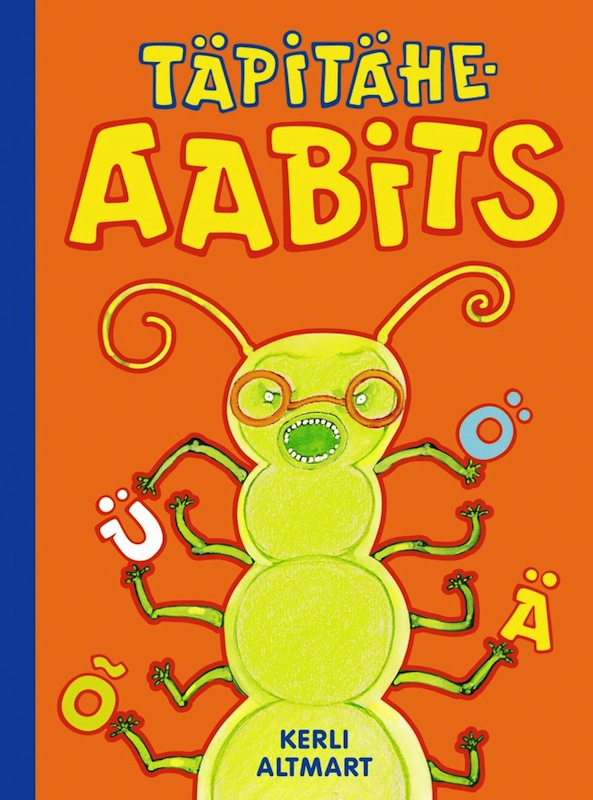

But do you know what order they are in? Logic might say that they should mirror the order of the same letters without diacritics; in other words perhaps Ä, Ö, Õ, Ü? NO. They way I finally managed to remember the order is to acknowledge the particular uniqueness of the letter Õ. It definitely deserves to be the first täpitäht in the parade.

“The most distinguishing letter in the Estonian alphabet is the Õ (O with tilde), which was added to the alphabet in the 19th century by Otto Wilhelm Masing.” Did you know that “It is almost identical to the Bulgarian “ъ” and Vietnamese “ơ”, and is used to transcribe the Russian “ы”.” (Source: Wikipedia.) I personally was aware of the existence of a similar sound in Russian, but not of the other exotic parallels. Ühesõnaga, (in a word) Õ leads the pack. The others follow suit logically, mirroring their dotless counterparts making the alphabetical order: Õ, Ä, Ö, Ü.

What about X, Y and Z you ask? These and many other letters in Latin script occur only in loanwords (laen/sõnad) and foreign proper names, not in Estonian words. Thereby, when the alphabet is written and recited without the letters appearing only in loanwords it has a mere 23 letters: A, B, D, E, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U, V, Õ, Ä, Ö and Ü.

What about X, Y and Z you ask? These and many other letters in Latin script occur only in loanwords (laen/sõnad) and foreign proper names, not in Estonian words. Thereby, when the alphabet is written and recited without the letters appearing only in loanwords it has a mere 23 letters: A, B, D, E, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U, V, Õ, Ä, Ö and Ü.

From this bare bones tähestik comes the name of the first Estonian alphabet book or reader compiled and published in 1795 in Tartu (“Tartolinnas”) by the same Otto Wilhelm Masing of Õ fame. It was entitled “The ABD”. More precisely: “ABD ehk Luggemise-Ramat Lastele (kes tahawad luggema õppida).” The title, showing archaic spelling now considered incorrect, translates as: The ABD or Reading Book for Children (who want to learn to read)”.

Pronouncing ABD and ABC led to the genesis of the word AABITS, the Estonian word we now know as alphabet book, ABC-book, reader or primer. It is interesting to note the Abecedar was a school book first published in Athens, Greece in 1925 and is also the name of the primer (1st grade school book) in Romanian.

One notch up from the bare bones, the official Estonian alphabet however adds four more letter (F, Š, Z and Ž) for a total of 27 tähed: A, B, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, Š, Z, Ž, T, U, V, Õ, Ä, Ö and Ü. Still no Y. Estonian philologist and language modernizer Johannes Aavik (1880-1973 in Stockholm) insisted that the letter Ü be replaced by Y, as it has been in the Finnish alphabet, thereby taking a step away from the German connection. That didn't quite catch on, although some poets prefer Y (pronounced “igrek”) to Ü, as does the Maavalla Koda – literally Hall or House of Estonia, short for Taarausuliste ja Maausuliste Maavalla Koda, it is an organisation uniting adherents of two Estonian native religious denominations, Taaraism and Maausk.

The letters F, Š, Z and Ž are so-called “foreign letters” (võõrtähed), occurring only in loanwords and foreign proper names. Growing up and going to Eesti Täienduskool in Toronto I don't remember learning Š and Ž and still get their pronunciation mixed up. They seemed to be Slavic in origin and somewhere along the line I got the (wrong) impression that they must have been forced on us by the Soviets. Šokolaad? Šampoon? Massaž? Surely not Soviet concepts! For lack of key use they can be spelled shokolaad, shampoon and massazh, but that is officially considered incorrect (you won't find such dictionary entries). And it makes words like dušš (shower) quite problematic (dushsh?!)

While we're on the subject of š (pronounced “shaw”) and ž (“zjeh”), if you're under the shower, you drop one š (duši all) and then should step out of the dušš before applying ripsme/tušš (mascara). The latter derives from the word tusche – a black liquid used for drawing in lithography and as a resist in etching and silk-screen work. German “tuschen”, to lay on colours / touch up with colour or ink.

One more addendum. While C, Q, W, X and Y do not occur in Estonian words, they are used in writing foreign proper names. Therefore upon including these “foreign letters”, the alphabet can consist of the following 32 letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, Š, Z, Ž, T, U, V, W, Õ, Ä, Ö, Ü, X, Y. But the 27 letter one is official.

Perhaps most important is knowing the order Õ, Ä, Ö, Ü and …R, S, Š, Z, Ž, T… It's actually quite logical to cluster those foreign cousins together around the original Estonian S. It's rather refreshing to not have Z as the eternal caboose.

Believe it or not, there's more to share on the subject of dots and twiddles – the latter being one online dictionary's cute English equivalent of kapsa/raud. But in what context?… To be continued.

Riina Kindlam, Tallinn