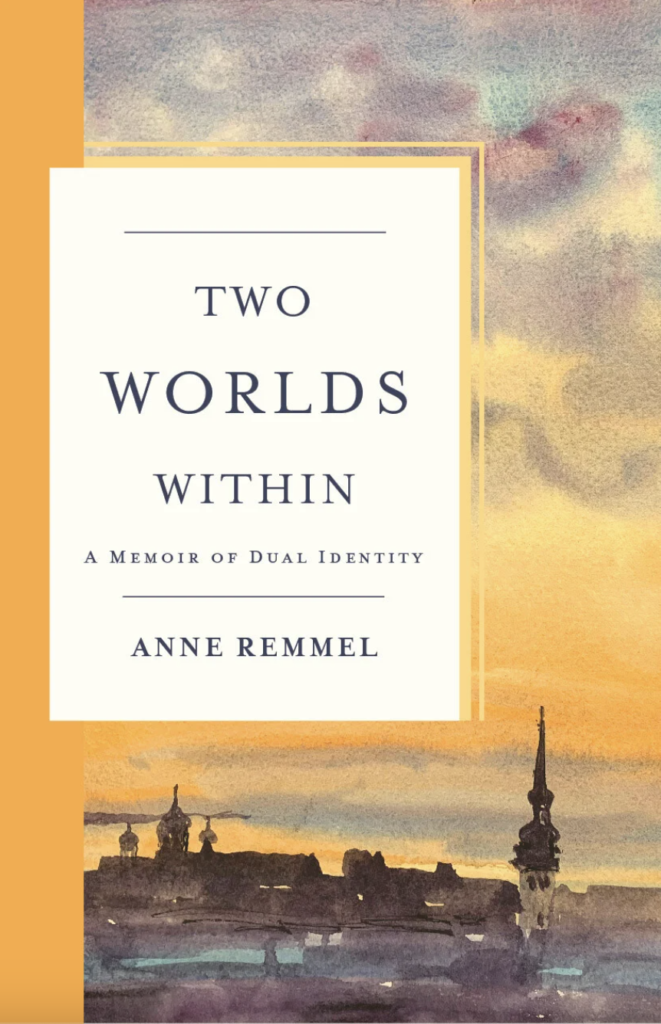

With the 80th anniversary of the Suurpõgenemine (Mass Flight) being commemorated this month, studying the nature of the Estonian-Canadian identity (or Canadian-Estonian depending on how you look at it) is at the forefront, discomfort aside. And Anne Remmel’s memoir Two Worlds Within – A Memoir of Dual Identity is a valuable written element of that study this year.

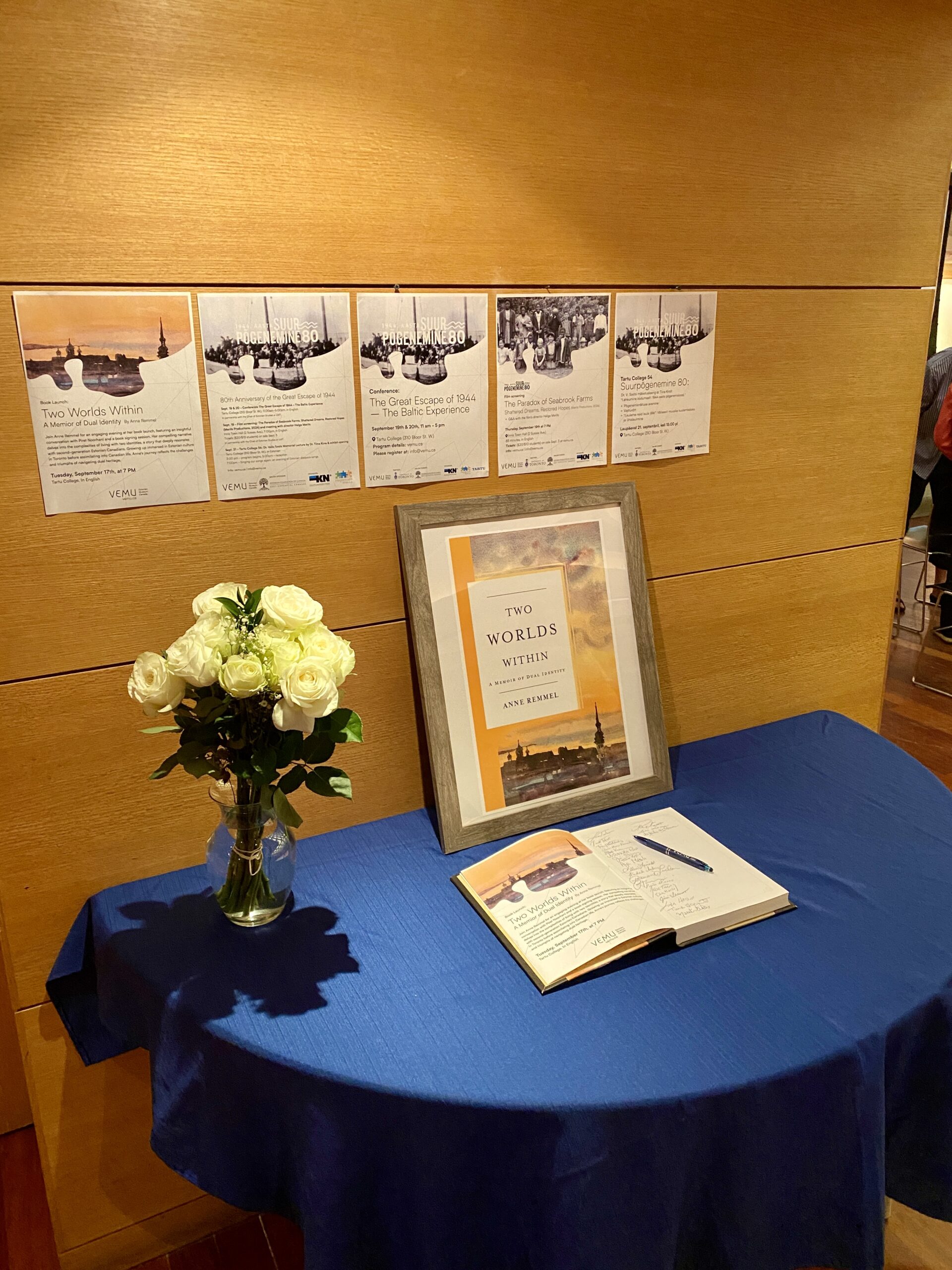

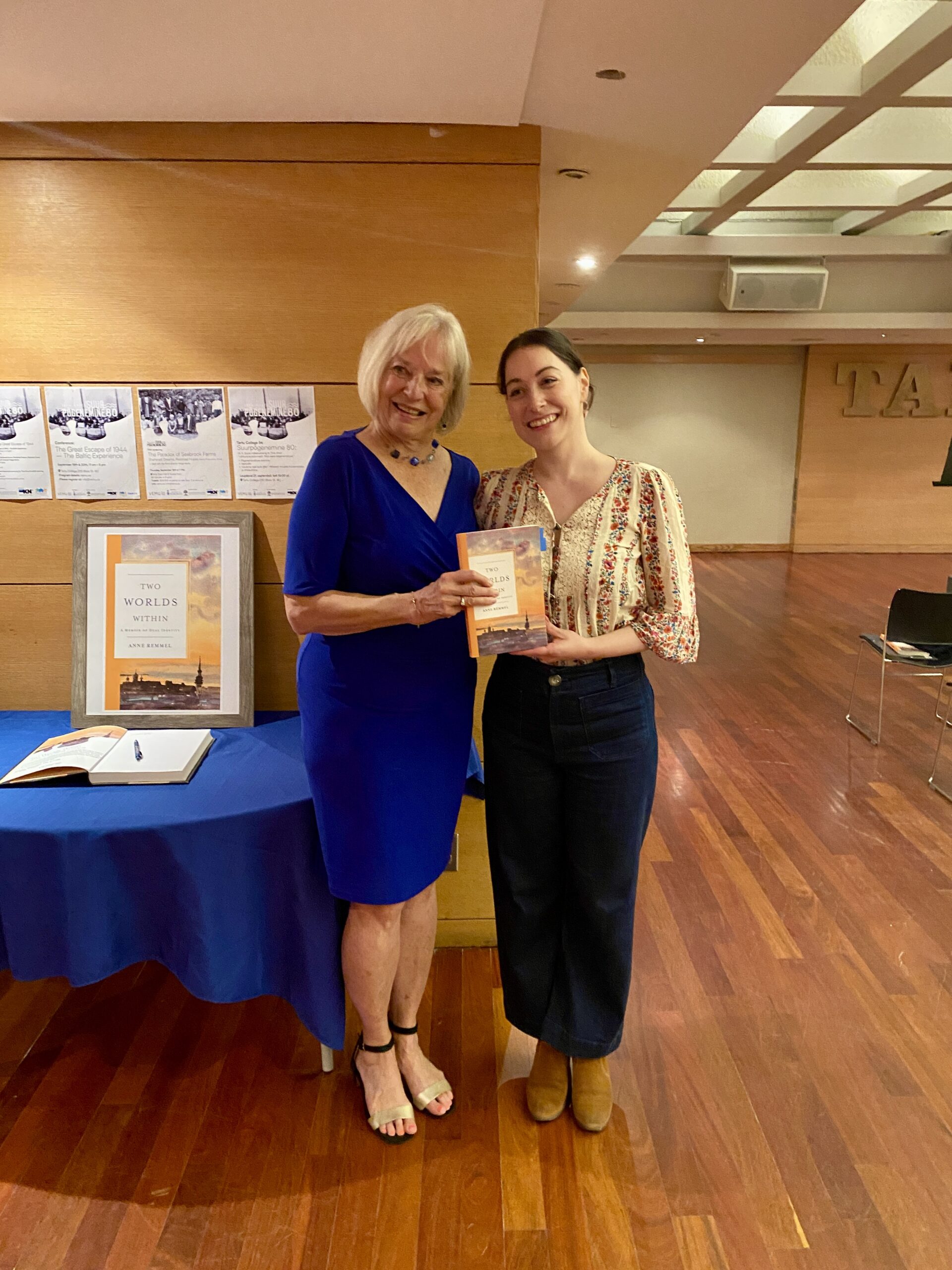

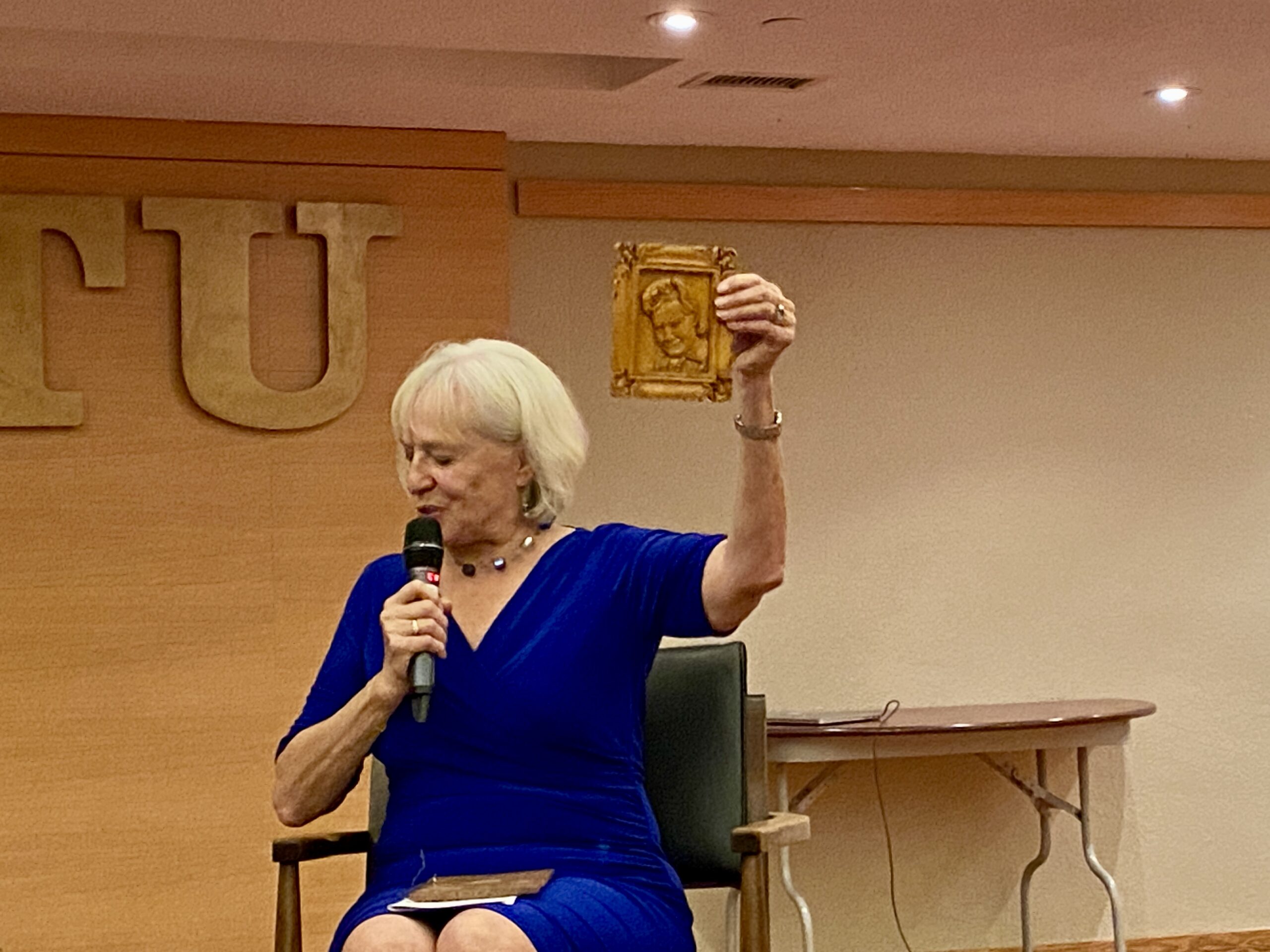

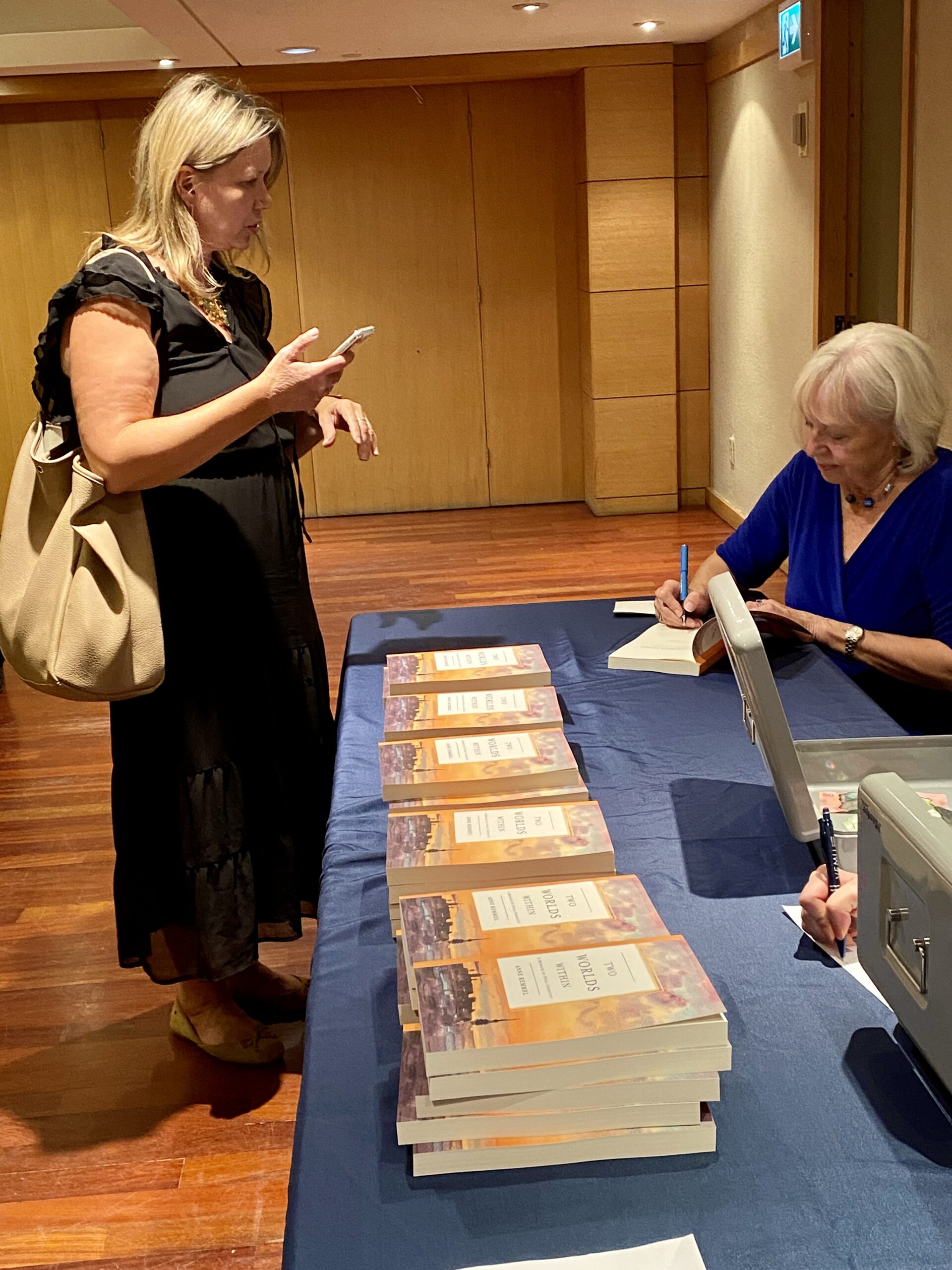

At her book launch on September 17th, a large gathering at Tartu College listened as VEMU Estonian Museum Canada’s chief archivist, Piret Noorhani, asked Remmel about the creation of her book. Audiences learned about the book’s first iteration, a search for her father’s story; how history repeating itself in recent years instigated her writing; the personal faith and loved ones that helped her and her parents to endure in times of trouble. Remmel also spoke to the surprises in her research that made crafting the memoir more difficult.

But asking tough questions and unearthing surprises is something she has grown used to. It can even be therapeutic, all of this searching for answers.

From early on in Remmel’s life story, we hear her voice calling out, questioning. She asks, “Did my mother imagine that she would be a landlady in Canada when she grew up in Estonia?” ; “Who was I really?” ; “Maybe I was a good little actress?” These and others are all relevant questions. Indeed, in modern society, where staying in one stable place increases the likelihood of accumulating wealth, connections, and opportunities, Estonians overseas could question how their lives would be different if war and occupations never happened.

And the questions continue, the ups and downs of Remmel’s life being the only path to answers.

Remmel asks, “How much was my immigrant child’s fear of poverty and fear of not ‘succeeding’ at play?”

As a little girl, we see the author on a balance beam between making her loving, hard-working parents proud and relishing in the delights of a 1950s Canadian childhood. We see the imprint of Estonian identity in her parents’ rules, like when the tagasihoidlik (modest) way of behaving increasingly squashes her dream of being an artist. That’s something many children of immigrants in North America could relate to: the importance of keeping your head down and pursuing a secure career over one that’s expressive and risky. As Remmel asks, “How much was my immigrant child’s fear of poverty and fear of not ‘succeeding’ at play?”

This concept is particularly jarring when, at the University of Toronto, she diverts from English literature studies to occupational therapy and attends three weekly classes of anatomy, dissecting cadavers. Followed by another shift; a series of clinical rotations assessing those accused of murder before their trials. In her inviting, conversational style, Remmel details the mindsets, traumas, and worries of Estonians in Canada. She brings us by her side along some of the most tumultuous turns of her multi-identity life.

Photo gallery

At the same time, Remmel’s book is a cross-section of Estonian dreams, passions, and victories. We’re reminded of how Estonians supported each other, pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, and built successful communities and individual lives with what they had. Often acting on each other’s advice and impressions of a new country. It’s eye-opening for young people today to read, as we try to climb up and make the best of our own set of circumstances.

In her own family progression from the 1940s to the 1990s and after, several parallels to the steps of other Estonian refugees are witnessed. A rapid marriage during the war. The coastal escape route to Sweden. A second uprooting and voyage to Toronto via Halifax. Correspondences with separated family members. Nerve-wracking visits to occupied Estonia in the 70s, where she sneaked past the “watcher” who tracked visitors’ movements in the Viru hotell.

One of the most stirring sections of the book is halfway through, with the rising of tension as Remmel drifts away from tight-knit Estonian community life into academia and a new circle of friends and peers.

In a way, this memoir is the shared experience of the Suurpõgenemine. If you grew up hearing your parents or grandparents talking about their memories, it’ll feel familiar. Indeed, if you grew up in the same generation as Anne Remmel, you may identify with her thoughts. If you’ve never heard about any of this, the book is an excellent place to begin, being a personable and gripping historical account. The memoir’s chapters comfortably alternate from relationship musings to discussions of sociology and significant heritage sites, with the result of wanting to know more throughout.

One of the most stirring sections of the book is halfway through, with the rising of tension as Remmel drifts away from tight-knit Estonian community life into academia and a new circle of friends and peers. Radical ideas and the heartbeat of old school Toronto ring out in this part of the book. As does a close insight into a traditional Anglo-Canadian family. There are quite a few aspects of her life that she had to conceal and filter out at this time, which makes us wonder how things will pan out. We get brand new perspectives, such as Estonian-American Vietnam War “draft dodgers” coming to town. In this situation, she imagines, “My parents must have wondered why any Estonian young man would not want to fight the communists?”

We know that the author re-engaged with her roots — this book was published for one thing — but how that happened, what we read about loss and about the personal encounters that altered her direction, are reasons to read this book. You’ll go through flames of conflict, but these flames offer us a chance of rebirth and harmony on the other side.