The album includes two discs and thirty-eight songs of music produced in France, with songs by artists such as Cesária Évora, Tony Allen, and Richard Bona. What I missed in terms of practicing phrases was made up for many, many times over by the music, and also an introduction to cultural giants, predominantly from African nations (the first three artists mentioned represent Cabo Verde, Nigeria, and Cameroon, respectively). I played the album so much, the notes of each instrument and singer are deeply planted in my brain. Particularly memorable, though, was the music from the West African nation of Mali.

Kora Jazz Trio’s song “N’dyaba”, was unlike anything I’d heard before. Over a foundation of dexterous piano and percussion that really pops, the peaks of the song are the impassioned calls from the singer, and… what’s that? Some kind of harp, plucked and with a wide range, from delicate high pitch notes to warm lower notes. The player of this instrument, also the singer, Djeli Moussa Diawara, cascades down the strings, creating what’s like the musical equivalent of a rainbow.

Some say it was invented in the 1700s, while others say its origins go as far back as the 13th century. For context, Mansa Musa was king of the Mali Empire between 1312 and 1337, an affluent era from which came the myth of Timbuktu’s streets being paved with gold.

Some time after this, having grown to admire Mali while studying it in a geography course, I finally learned what the instrument is called. While in Venice, crossing one of the city’s many bridges, I saw a man busking, creating familiar sounds while plucking the strings of a kora.

As The Kora Workshop in the UK describes it, “The Kora is essentially a harp-lute; there are no frets and there is one note per string. It has 21, sometimes 22, strings made from fishing line [nowadays].” These strings are attached down the length of a wooden neck and are extended across a bridge. This bridge is attached to a cow hide-covered gourd, which is where the sound resonates. It’s a historic instrument, originally from The Gambia. Some say it was invented in the 1700s, while others say its origins go as far back as the 13th century. For context, Mansa Musa was king of the Mali Empire between 1312 and 1337, an affluent era from which came the myth of Timbuktu’s streets being paved with gold.

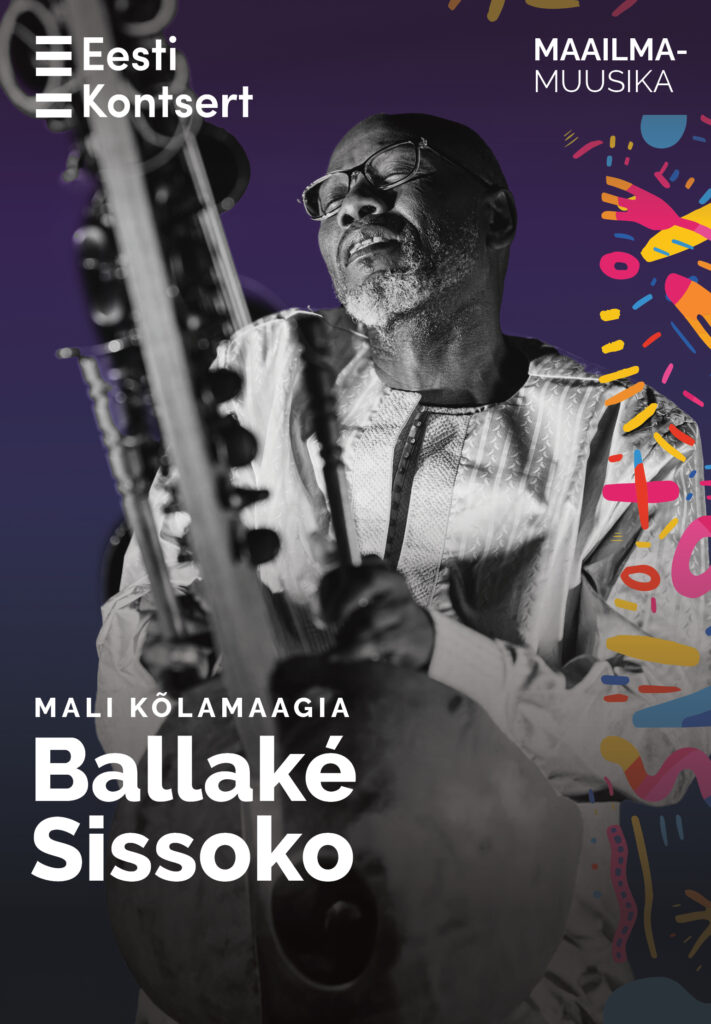

As a listener and a cultural outsider, listening to the kora brings to mind the scenery, cultural richness, and history of Mali. When listening to songs with kora, such as the work of Malian master Ballaké Sissoko, one can imagine vast libraries made from adobe, like temples of knowledge, fishermen and lush crops on the Niger River, or the enjoyment of flavours and company in Malian tea ceremonies.

There’s a feeling of calm and focus in kora music. And another reason kora music is comforting may be its relation to the blues, the source of contemporary North American music. American blues musician Taj Mahal once said “Sometimes when people talk about the connections between Afro-American music and African music, they’re kind of stretching it…” But when playing alongside Malian musicians (including Toumani Diabaté), he spoke of familiarity, noting “It’s almost like a relative who’s gone away for 500 years and gone through some metamorphosis and changes, but is still recognizable.” Educator and blues harmonica player Ray Harris specifically points to the kora’s “complex and melodic fingerpicking style” as a “forebear to the rich Delta blues guitar sound of Mississippi John Hurt and others.”

Tallinn residents are fortunate that Ballaké Sissoko brought this wonderful music and instrumental expression to the Estonia Concert Hall on February 19th, 2025, along with a pre-concert screening of the documentary Ballaké Sissoko, Kora Tales (its trailer can be found on YouTube), which details the history and use of the instrument. It’s a part of music culture that has not been shared in-person at all—or at least not on a significant scale—in Estonia before. And there are parallels to the traditional folk instruments of Estonia, namely the kannel. They are both plucked stringed instruments, with usage of the kannel going back thousands of years according to Eesti Kunstimuuseum. They are both key to the passing of knowledge and memories. Traditionally, people from Jali (a hereditary caste of the Mandé peoples as The Kora Workshop explains) families serve as praise-singers, historians, and storytellers, with accompaniment on the kora, balafon (a gourd xylophone), or ngoni (a lute). Likewise, folk instruments in Estonia are and have been involved in the relaying of stories and ancient songs.

Sissoko has not only broken ground with regard to bringing West African musical traditions to new audiences, he’s shown how they might fit together with other regional traditions. Take, for instance, his recent tour with English singer-songwriter and guitarist Piers Faccini, or his NPR Tiny Desk Concert with French cellist Vincent Ségal.

In these contemporary songs, in these performances, and in the study of history, we should remember the valuable role of storytellers, bards, and people who pass along our memories and songs in society.