In this issue, Eesti Elu and Estonian Music Week continue to share articles from the VEMU Estonian Museum Canada archives, about memorable events of the past. Read on for a thorough description of the trials and philosophies of composer Arvo Pärt, originally published in Vaba Eestlane issue number 88 on December 10th, 1981.

Arvo Pärt spoke about himself and his music

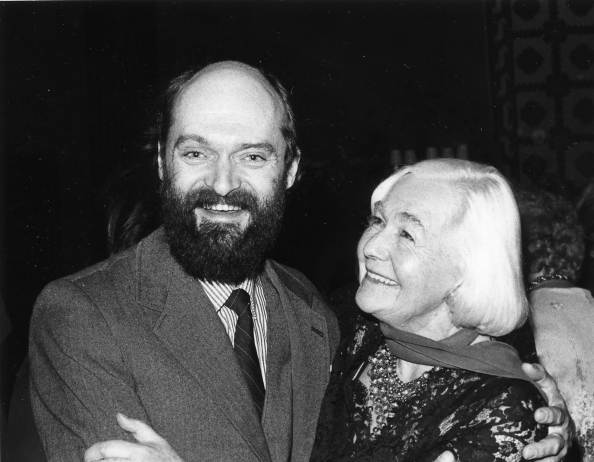

Interest in musical guests has been high in Toronto, and on Monday evening, Tartu College was packed with music lovers for an event introducing Arvo Pärt’s compositions. Since the other guest conductor, Neeme Järvi, had a cold and was tired from a very strenuous orchestra rehearsal, A. Pärt himself gave an overview of his life and musical works and performed some musical works from an audio tape.

A. Pärt said that after two years spent abroad, he had begun to miss Estonian audiences. He apologized several times that speaking was not his specialty and that he had already realized that he could not talk about his music and thought that he shouldn’t do it.

His musical works were practically born out of nothing, after long silences.

Every completed opus is a finished work, to which the author’s comments seem superfluous, and violence must be used when analyzing a work that has already been molded.

He claimed, however, that sometimes he contradicted himself. When creating music, every expressed thought is final, and by supplementing and changing it, a new creation is obtained. He still advised listeners to listen to his work and that he would be happy if listeners expressed their own opinions about it.

Describing his creative style, he said that music-making is preceded by a pause. He tries to hear something from this silence, from micro-oscillations. To call it concentration would be an understatement.

Silence—a pause is the embodiment of the soul, although there is some movement at the beginning of several compositions.

For example, in 1977, he performed the piece “Tabula rasa,” composed for two violins, which is one of his best-known works and has been performed up to twenty times in the West. The next time will be in New York in January.

Speaking about himself, he said that he is not some kind of musical prodigy. His parents were not musicians either. He was made to study music because a music school was founded in Rakvere and they had a piano. He also became a composer by chance. Since he liked nuts, his mother gave him ten nuts for every ten repetitions of a piece during piano exercises.

… he also developed an interest in dodecaphonic (twelve-tone) music, which at that time had a bad connotation in Soviet society. He was considered a political criminal for studying it.

But alongside this, he began to play what was not in the musical notation.

This made the lessons shorter. But this arbitrariness ended sadly, when his mother and the piano teacher met. By then, however, Pärt had already learned the basics of composition. Instead of nuts, he received permission to improvise. He says that his further development was under the guidance of piano teacher Hille Martin, composers Jaan Paku, Veljo Tormis, and Heino Eller, graduating from the conservatory in 1963.

Alongside composition, he also developed an interest in dodecaphonic (twelve-tone) music, which at that time had a bad connotation in Soviet society. He was considered a political criminal for studying it. He learned it from the books that Eduard Tubin had brought to Heino Eller.

He said that while working for Estonian Radio, he had the benefit of the tapes there that others did not know about.

The first dodecaphonic work brought him into conflict with the official ideological leadership of the Soviet Union.

Then, unnoticed, musical collage entered his sphere of interest. This immediately became the carrier of his idea and took the form of “Credos” for piano, choir, and orchestra, created in 1968. The fate of the work was very complicated. After the premiere, conducted by Neeme Järvi, and which was repeated, it was banned with lightning speed. The composer and conductor are both currently in Toronto. Later, he had to explain in several “red rooms” what ideological considerations he had written it for. He played the aforementioned “Credo” from a tape that was made at the premiere in Tallinn.

A. Pärt said that by doing this, he had burned all creative bridges, renouncing himself from the arsenal of modern means of expression.

He had to start from scratch. During this period, he heard Gregorian chant for the first time. He found that music could consist of something other than polyphony, classical forms, dry calculations that the ear cannot hear or the eye cannot see, and that not everything is music.

The next three years were a time of creative silence. But it turned into a time of music-making and learning. “Symphony No. 3” was born, in which pain is expressed. He was absorbed in the effort of finding the origins of music and penetrating to the roots of music. Thanks to Neeme Järvi, this symphony reached listeners. Its characteristic is great simplicity. The performance of the work showed the conductor’s courage and insight at that critical moment for him. When most of his colleagues were cursing him, Järvi believed in his creation.

The symphonic cantata “Song for the Beloved” followed, with which he had “tortured” Järvi, since he had brought him a new version three times.

In 1976, he was forced to change his compositional system, calling it “bells.” He said that he had not yet exhausted all its possibilities, although he had created about twenty works. It’s an extremely simple system in which he takes a simple melody and tries to create a second voice using only three notes. An example of this, “To Alina,” was performed by Hillar Liitoja on the piano.

The piece for male choir, organ, and percussion—“Profundis,” completed this year in Vienna—was commissioned by Kassel Church, and was also played from a tape.

“Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten,” which is on the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s program, has been played the most among his works with the help of Neeme Järvi. A few months ago, “Credo” was played in Scotland. Thanks to “Cantus,” the Estonians of Toronto invited him here, for which he expressed his greatest gratitude to those present.

Finally, he revealed information about his personal life: he is married and has two sons, named Emanuel and Miikael. The family currently lives in West Berlin, where he himself is an honorary fellow of the German Academy.

… it was from this point that he had found his homeland, had a completely different image of it, and was now more attached to Estonia than when he lived there.

After the presentation and musical samples, there were some additional questions. Among other things, he was asked how leaving his homeland had affected him. He replied that it was from this point that he had found his homeland, had a completely different image of it, and was now more attached to Estonia than when he lived there. Now, like other refugees, he has come to understand that Estonia is all over the world. This is a completely new feeling.

He feels that he can express himself creatively in the current situation, because in his homeland, the possibilities for self-expression were suppressed all the time.

But it will take time before all the knots are untied and he can become a “free bird.”

He described Järvi as a miraculous person who was able to flourish in that “basement,” which dazzled everyone. Now he can devote himself one hundred percent to his calling.

When asked about the concept of freedom in his homeland, he replied that it is a great risk to allow yourself freedom, but you can never be truly free. The greatest freedom for a person is to be free from sin. With this, as in his musical works, the conviction of a deeply religious person came to the fore.

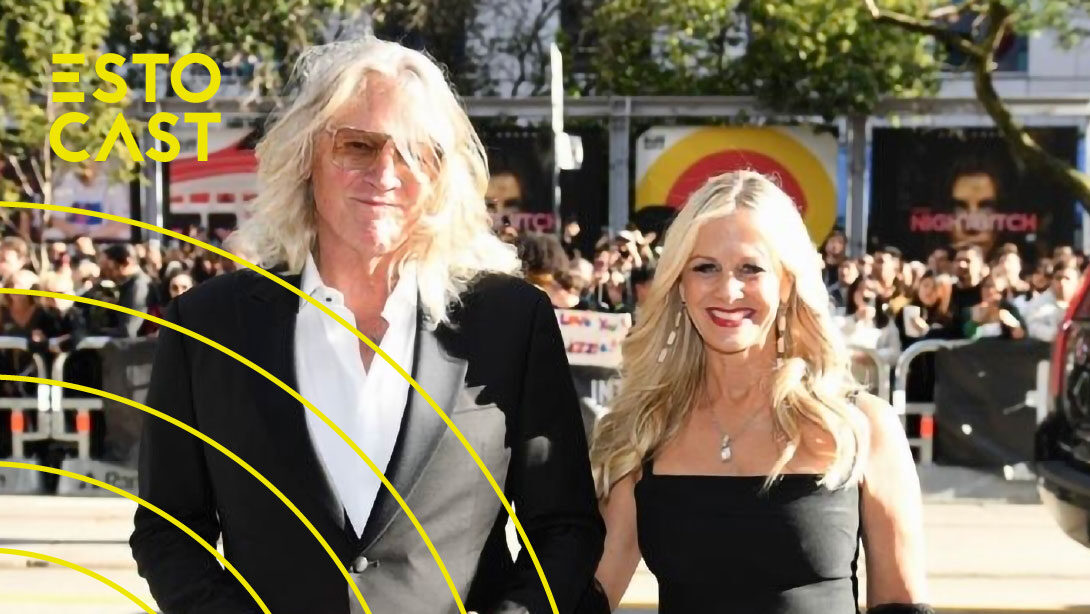

Finally, Stella Kerson, president of the Estonian Arts Centre, thanked Arvo Pärt with red roses and said that the evening was jointly organized by three organizations, in addition to the aforementioned, the Estonian Central Council in Canada and the Tartu Institute.

On the evening of Sunday May 25th, celebrate the 90th birthday of Arvo Pärt with a performance of his music by Grammy-winning choir Vox Clamantis. Tickets and festival passes are available at 2025.estonianmusicweek.ca/tickets .