Triumphant melodies and hopeful messages reminiscent of peacetime—even those concealed due to censorship from the state—can brighten even the darkest of times. This has been especially true for Estonians who lived under the Soviet occupation. Those who are familiar with Estonia’s national song festival know that in the face of hardship, choral and folk music lives in the collective imagination of Estonians as a continuing symbol of peace and freedom.

But another genre of music also kept Estonia’s cultural identity alive during the Soviet occupation.

Progressive rock (or prog rock) is witty, experimental, and strikingly fantastical. Inspired by earlier psychedelic rock, prog rock’s pioneers in the late 1960s—including The Moody Blues and The Beatles—embraced creativity in the production and writing process, fusing hard rock with jazz, classical, and folk to create a sound that transcended the boundaries of what we now call classic rock. Albums were created based on an overarching (often abstract) theme that was meant to extract listeners from their reality into a distant fantasy. Prog rock concerts materialized these themes by putting on shows of extravagance and grandiose theatrics. English prog rock band Genesis went as far as creating unique stage shows, during which front man Peter Gabriel dressed up in costume to act out the various characters portrayed in the lyrics in their 1972 record, Foxtrot.

New, funky, and uniquely bold; it was undeniable that prog rock altered the fundamental rules of how rock could be created and enjoyed. But these defiant characteristics were not accepted everywhere in the world, especially in the context of the Cold War. The Soviet Union vehemently opposed Western culture and worked to prevent any of its influence from seeping through the Iron Curtain.

Like a noxious poison, the Soviet state thought Western influences would spread through the veins of society and disrupt its morals from within. This included music—especially rock music—that was popular in the United States.

Yet the Soviet Union could not prevent the inevitable spread of shaking and boogying, nor the twisting and shouting popular in the West. When the hippie movement eventually reached the Soviet Union in the 1970s, state officials were concerned that their society was crumbling before their eyes. Aare Purga, the then-Secretary of the Central Committee of the Leninist Young Communist League in Estonia, wrote in a letter to Moscow officials that:

“In the summertime, young people gather on the streets and other places, and there are lots of so-called ‘longhairs’ among them. Their appearance – long hair, outlandish clothing – and a sloppy manner popularizes degenerate Western ‘fashions.’ During the last two years, but especially in 1969, the habit of imitating Western ‘hippie’ fashions in a vulgar way has increased. Some of the young people have started wearing long hair, which in some cases even reaches the shoulders. The first to adopt these fashions have been the poorly educated constant club goers, including a steadily increasing number of working class young people.”

The increasing number of youth who imitated Western fashion can be attributed to the fact that Estonia had a relatively relaxed atmosphere and higher exposure to Western culture (compared to the rest of the USSR). Estonia’s connections to Finland and access to its television programs intensified this process.

Foreign radio broadcasts also exposed occupied Estonia to the world of Western music. Radio Luxembourg was especially popular for this. From The Beatles to The Rolling Stones, Estonians attentively listened to hazy, low-quality transmissions that captivated their minds and provoked a new yearning for what seemed like an alien world.

By the late 1960s, illegal trading, buying, and selling of these rock records became popular in Estonia. Despite the blackmarket’s best attempts at being clandestine, the Soviet Union was well-aware of their happenings. Alarmed by the music’s ability to undermine Soviet control, the USSR decided to offer state-sponsored (censored) rock music. Known as vocal-instrumental ensembles (VIAs), these bands were meant to simultaneously placate and reinvigorate its propaganda within the population. They were a success. Beloved by the older generations, VIAs sold millions of records and became the “de facto soundtrack of late socialism.”

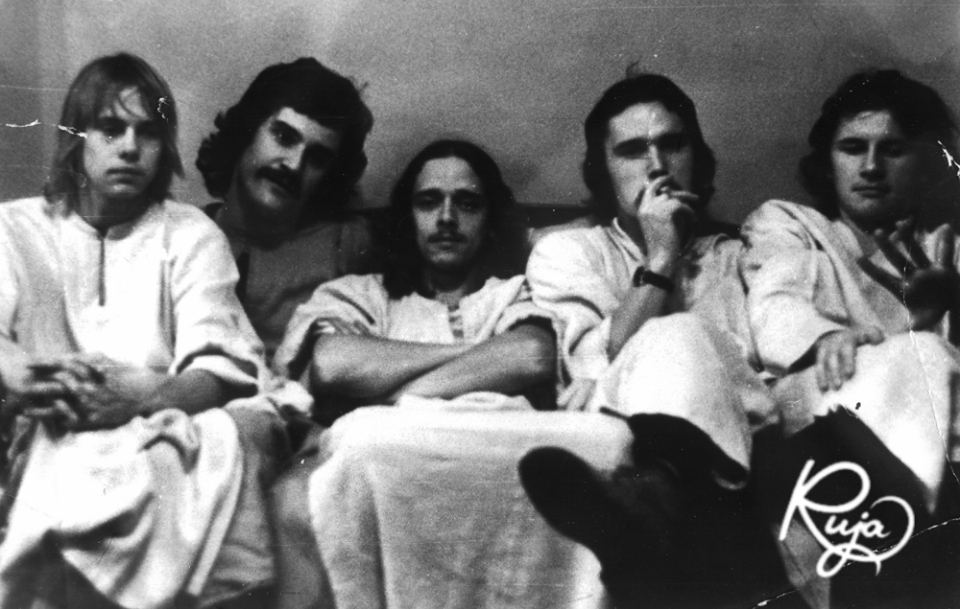

However, VIAs did not hold the same popularity in the hearts of the younger generations of occupied Estonians. Being censored by the state, VIAs had a “strict dress code that consisted mostly of suits, national costumes, and military uniforms, and had to follow Soviet ideology. But the imaginations of Estonians were ripe with fantasized versions and idealizations of the West. They needed something more that challenged “authoritative discourse, morals, militarism, censorship, cultural repressions, and proclaimed atheism” that was inherent to the Soviet Union.

Consequently, it was around this time that Estonia began producing its own prog rock scene. Concerts were held across the country. Whether Soviet observance was present or not, anthropologist Terje Toomistu notes that “they were nevertheless important sites of socialization and self-expression and a source of divergence…” from Soviet rule. At concerts where Soviet monitoring was present, lyrics of Soviet resistance and self-expression were buried in allegories and hidden meanings.

Paap Kõlar, member of prog rock band Psycho, describes his group’s musicality as such: “We were very protest-minded. So we ignored everything… Why does a piece of music have to have a form? Let’s try making music without form! …We tried doing songs without melody or harmony. We made fearless experiments. The more hopeless the surroundings, the more you needed to cocoon yourself in order to do what you wanted. As it turned out, it was possible to remain independent of that crap…”

Concerts weren’t the only way that Estonians could preserve their cultural identity under Soviet Rule. As a genre, prog rock itself played an important role too. The sound represented a way of going against the status-quo. It was defiant. It was extravagant. It was theatrical. It was everything the Soviet Union opposed, arguably even more so than classic rock.

As silly or flamboyant as the sound may be, prog rock continued to ignite the spark of resistance and hope in Estonians. Unsurprisingly, the genre became a significant influence in the Singing Revolution leading up to the country’s re-independence day, alongside choral and folk music. Many Estonians who lived through Soviet occupation hold prog rock close to their hearts.

This article was written by Natalie Jenkins as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.