How forces outside their control shattered everyday lives and forced people to abruptly change where and how they lived.

The first film at EstDocs is “The Woman in the Picture” by filmmaker Priit Valkna and featuring the extraordinary paintings of artist Lauri Sillak. The film was shot in a vacant wooden house in the heart of Tallinn that once belonged to the creator of the art of film and photography in Estonia, Johannes Parikas and his wife, Lilli.

The fact that this house is still standing is a minor miracle in itself. The history of the lives that were lived there – and interrupted so brutally by war and exile – is palpable throughout the film as artist Lauri skilfully brings to life a series of stunning installations of women’s portraits to line the old wooden walls.

One of the portraits is of Lilli, and it’s as if her spirit has inhabited the walls all these years and has now finally been able to emerge again. Perhaps her restless soul is somewhat calmed, now that this touching and beautiful film has enabled her to become available to us and present in the house she once loved.

Lauri painted a backdrop for the installations in the style of period wallpaper, William-Morris in design and visible in many of the old photographs of the Parikas household, and layered the portraits on top. Priit captures the artist at work in a series of scenes that show his concentration on the rather large task at hand and also his sometime exasperation and fatigue at tackling such a daunting project. Memorable scenes include Lauri stoking a fire in an old wood stove to keep warm while painting in the cold winter months and taking a nap in the only available resting spot – an old claw foot bathtub that somehow survived in the otherwise eerie and stripped bare house.

The film, which took five years to complete, also has old archival photographs from the Parikas archives woven throughout the story. Digitizing the photos was another masterful feat and they bring the history of the glamourous Parikas family, and the many notable artists of the day who were their friends and frequent visitors, to life.

This film made an indelible impression on me, one I won’t soon forget.

The second major film night featured “Come Back Free’, about how fighting continues in Chechnya. Russian director Ksenia Okhapkina shows the impact of the war on a village in the Chechnyan mountains and how everyday life somehow continues among the funerals and work of the gravediggers.

“Soviet Hippies” by director Terje Toomistu and produced by Liis Lepik is an eye-opening look at the hippie movement in Russia and how this original group of pacifists were persecuted and reviled. It follows the lives of several older survivors of the movement.

A group of these “elder hippies”, still sporting tie-dyes and beads and beards, travels to Moscow to the annual gathering on June 1 to commemorate the arrests of thousands of people by the KGB. The film pays tribute to people who were brave enough to buck against a system they felt was constrictive and violent. Many paid a high price for this freedom and independence of thought.

The Sunday afternoon of films at Tartu College is always a well-attended gathering and a full house turned out to see the films.

“Meite Kodo” is a film about the island of Kihnu, where 600 stalwart souls live. The population is decreasing and its inhabitants wonder how the population will survive as school enrolment drops and people move off the island. A visiting home care worker, who has returned to Kihnu from the mainland to care for the island’s elders, is kept busy looking after her patients, many of whom depend totally on her visits.

“Jaanipäev” is a lighthearted look at the many revellers who are waiting in the ferry lineup to Saaremaa for this annual summer celebration. A young man patiently traverses the rows of cars waiting for the ferry to sell dried fish he’s prepared so he can buy a new Playstation. His efforts pay off – many hours later his basket is empty.

“Raising of the Flag” is about a group of patriotic youth who raise an Estonian flag on the tower of Pikk Hermann in Tallinn on August 28, 1941 as the Russian army retreats and the German army advances.

“Holodomor: Voices of Survivors” introduces a tragic piece of Ukrainian history from 1932-33 to EstDocs, in which millions of people died of starvation in a famine engineered by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin.

Just when it seems as though my EstDocs experience is pretty much complete, and I am thinking that an evening of some bland Netflix offerings is about all I can handle in the aftermath, along comes “Paradise Behind the Fence,” which was shown on the last night of the festival. EstDocs wasn’t ready to let go of me just yet. This film tells the story about how Sotchi, Russia’s biggest summer resort, was chosen as the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics.

What Olympics-goers never knew was how an ancient community of Estonian settlers had to leave the land, homes and animals they had cared for over generations in order to make way for ski jumps, chairlifts and highways. The Olympics came and went, and the beautiful, mystical landscape in this mountainous region has never been the same since.

Again, lives interrupted.

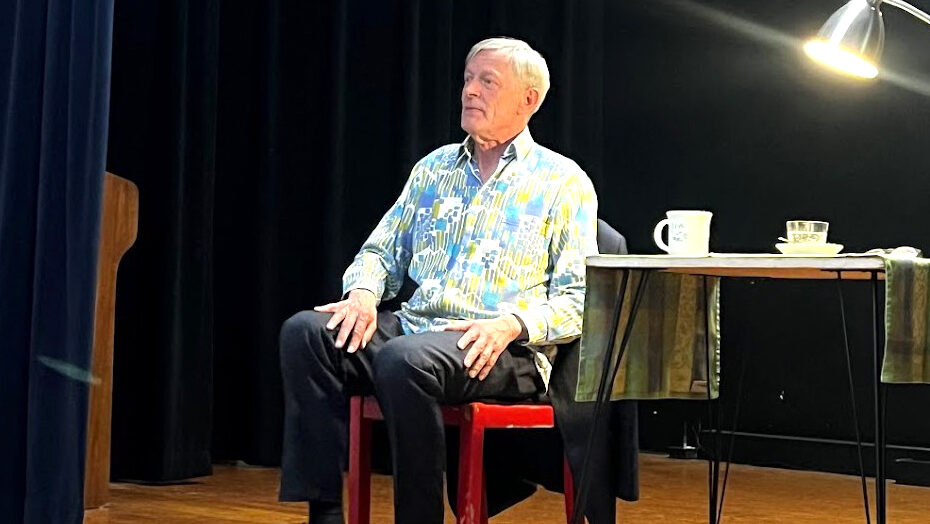

Estonian film critic Tristan Priimägi, who made his first visit to Canada to moderate EstDocs, did a masterful job introducing the films each day of the festival and leading thoughtful question-and-answer sessions. He also interviewed the filmmakers, many of whom attended the festival, so audience members could hear some of the back story around the making of the films.

Next year is EstDocs’ 15th anniversary. Every year, it is astonishing to me how this small country can produce such an explosive variety of art and film. I am humbled by the dedication and painstaking work on the part of the documentary filmmakers.

Festival Director Kristi Sau Doughty and her hard-working volunteers guarantee a festival worthy of this anniversary.

I have absolutely no doubt that this will indeed be the case, and that EstDocs 2018 will delight and amaze us once again.

Karin Ivand, Toronto