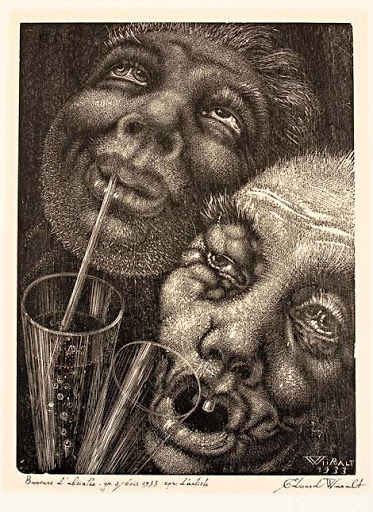

It's occluded by his most cited creation, from 1930, called “Põrgu” (“Hell”). But by 1933, when he made “Absinthe Drinkers”, Wiiralt was eight years into his first era of Parisian life, and this is the best way to see a city that meant a lot to him. A city he would try ambitiously to return to from Estonia, before the Second World War was fully over. The city where he would eventually pass away.

It's his most Parisian painting. It positions his work within the myths of the City of Lights and the energy of what was happening underground. “Absinthe Drinkers” was made 15 years after absinthe was the subject of protests and made illegal in France, only to become legal again in 1988. Already, “the green fairy” was infamous for its affects on the health of drinkers, either for its high alcohol content or the volatile combination of fennel, green anise, grand wormwood (artemisia absinthium), and other herbs.

Wiiralt's wood engraving is unlike any other characterization of absinthe that came before or would follow after it. It's unclear if the individuals in the engraving are based on people he knew or simply people he observed after arriving to the excitement of Paris at age 27. The image is counter to the melancholy and soft solitude that we see in the depictions of absinthe from Manet (1859), Degas (1876), or Picasso (1901). It abstains from illustrating an actual fairy or muse, as done by Albert Maignan (1895) and Viktor Oliva (1901). If paintings about this concoction were already once the cause of offense and indignation in the art world, then the way Wiiralt represented absinthe in fuzzy and ecstatic tones was even more potent. Although, art salons, critics, and collectors had several years to find other subjects controversial instead.

Each figure in the engraving has an additional iris forming on one eyeball. The drinker on the left drinks gleefully through a straw, head tipped back to the sky. The drinker on the right is almost dentally bankrupt and tilts his eyes in no particular direction. While other Wiiralt engravings have subjects more or less stuck somewhere in a static moment, this image focuses on two characters passing through a process of demolition and disorientation. With the aforementioned painters, we see absinthe drinking before it precipitates into something wilder and maybe even gratifying, as in Wiiralt's work. As Oscar Wilde purportedly said, “After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

Tiina Abel of Kumu Art Museum has said “The most fantastic drawings and prints belong to the period between 1925 and 1933, when the artist followed the bohemian way of life and was possessed by his work…It was a turning point.” Even later, in terms of art that Wiiralt created after leaving Paris in 1938, his work takes a mostly softer tone, inspired by the people and animals he encountered in his travels, including a period in Morocco. It's not always fitting to try to identify constant themes in an artist's work, but his portrait work keenly observes less “glamorous” emotions.

Eduard Wiiralt is reported by Eesti Ekspress to be the most counterfeited Estonian artist. His perception of the gloomy facets of places he lived, and the ability to share that visually without self-censorship is part of the celebration of his art.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.