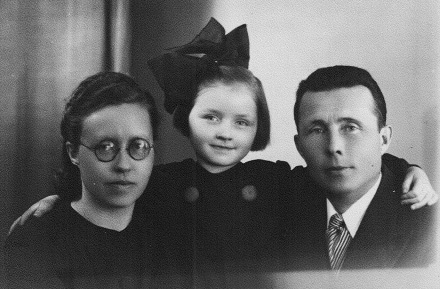

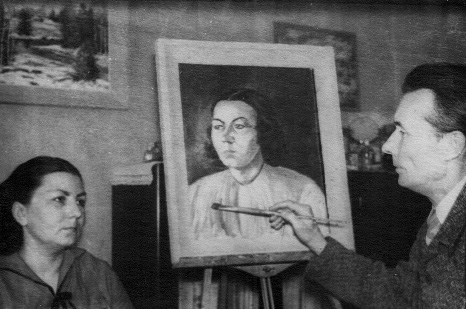

Hele was given her name by her adoring father Heido Laarne. He felt that Hele, “light”, generated a positive and lucky future for his daughter. Names were important to Heido. He was born Ervin Laarman but changed his name to Laarne during a period when there was a national interest in sounding “more Estonian”. Heido was a journalist who worked for a newspaper in Pärnu and also provided skills as a commercial artist, usually with calligraphy, sign painting and decorative design. Heido’s time at home included formal painting with oils to practice skills with portraiture and landscapes. His cousin Märt Laarman was a successful professional artist and cubist printmaker.

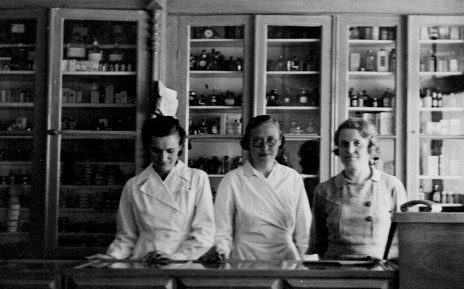

Heido spent his childhood growing up with many relatives and friends of the Laarman family. He married a childhood friend Hella Sillaots, the daughter of a widower, Sea Captain Jakob Sillaots and his wife Anu. Hella was a bright student at school and eventually studied and worked as a pharmacist at Adamsoni Apteek in Pärnu. Hella and Heido had a home in the old part of Pärnu with a large property and both welcomed a daughter Hele who became the centre of their family unit. Vanaema Anu lived with Hella and Heido and Hele’s bond with her grandmother was very special. Heido’s sister Alma was a professional nanny who cared for Hele while Heido and Hella worked in downtown Pärnu.

Hella was fond of maintaining a large garden and Heido spent many hours with Hele by their lilac trees saying “otsime õnne”, “let’s find good luck” while searching for a five-petalled lilac flower. My mother Hele has said many times during her life that that moment of being held in her father’s arms in the beautiful garden was a lasting memory of love and safety for her. His singing voice, together with Hella’s, was trained for years by singing with the Eliisabeti kiriku koor.

A photo of Hele’s loving relationship with her father is central to my art piece. I understand from my mother that Heido imbedded a core value of gentleness, positivity and humour in their family relationships. Hele’s appreciation for art developed in the presence of her father and other relatives like her Onu Märt Laarman.

Hele was seven years old when the decision was made to leave home because of the fear of invasion as the Soviet troops advanced with their artillery. The sense of panic was everywhere. Rumours and stories were rampant about a knock on the door in the middle of the night and families forced to leave their homes and sent on trains to Siberia by the Soviet invaders. Those who waited until the very last moments as the heavy artillery was approaching the city, rushed to the fishing boats in the port of Old Pärnu. A neighbour recognized Hella, Heido and Hele at the docks and said that only one more could fit onto their overcrowded boat. Hella came forward with Hele as Heido insisted he would hopefully meet his family somewhere across the rough Baltic Sea by travelling in another boat. He was told to meet with a few people in Seliste as their small boat was leaving early the next day. Unfortunately those individuals were anxious to leave earlier than planned and my Vanaisa Heido ended up staying in Pärnu for the duration of his life.

As Hele explained the escape to me, she said that the Estonians on the boat agreed that this was a temporary measure. The hope was that the war would end soon and they would return home. The harrowing boat ride included a moment when the boat’s engine stopped in the darkness of night. Feodor Homits, another close neighbour from Pärnu, was held by his ankles and lowered below the deck with a few tools and a small light to fix the problem. The boat was covered by tarpaulins to prevent being spotted by overhead enemy planes. Feodor was eventually able to repair the engine and the boat continued its movement until enough light at daybreak illuminated their location-right back to where they had started. The navigators had somehow directed it the wrong way. Panic set in again as they headed back out to sea.

As my mother explained, from her perspective as a child the rough sea voyage brought on a huge issue of sea sickness. Her next memory was of the boat arriving somewhere and coming to a stop. Someone had spotted land. Hele was then in the strong arms of a young adult male wearing water-waders. The seawater was still choppy but the Swedish man carried her to the rocky shores of an island and my mother stated that it was Gotland. I never asked much more about that experience. On occasion as I got older my mother would mention that same strong memory a few times and the image always stayed with me. I knew this had to somehow be included in my art work.

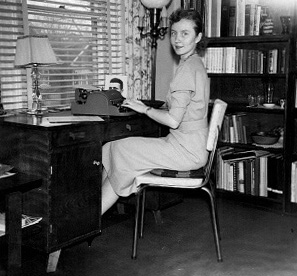

Later as an adult I heard about my grandmother Hella helping to assist Dr. Tammemägi with ill and recovering Estonian refugees in quarantine. Hella eventually went to Tidaholm with her daughter Hele, as there was a small pharmacy there where assistance was needed. She passed her Swedish exams to work at the pharmacy. They lived there with other Estonians and integrated into the small town community. At age 13, Hele and her mother Hella came to Halifax, Canada on another ship, the SS Stavangerfjord, as many Estonians were again fearful of being sent back from Sweden to Estonia, their country of origin, which was still under Soviet rule.

Close to eighty years later, the legacy of the refugee fishing boats on Gotland and Färö Islands was examined by a Swedish archeologist, Dr. Mirja Arnshav. By chance while visiting Gotland, Dr. Arnshav noticed a deteriorating boat made of oak with a construction different from that of Swedish fishing boats. Her curiosity led to a major research project about the escape boats and a film by Estonian journalist Maarja Merivoo-Parro. At the tip of Gotland, in Färö, Dr. Arnshav found more escape boats and stories about Estonians and Latvians, some 10,000 of whom had arrived there. Kerstin Blomberg, a current elderly resident of Färö, explained to Dr. Arnshav about her memory of a relative in the lighthouse who put on his water-waders to bring people from the boats to the shore.

All the symbolic images needed for my art work became clear to me. The grey oak planks became the background for my art piece. Like treasured artifacts, these remains of the boats held the story of hope.

Suddenly I felt connected to my mother’s story of her rescue because of Dr. Arnshav’s curiosity about the oak planks decaying in the tall grasses of Gotland and Färö. All the symbolic images needed for my art work became clear to me. The grey oak planks became the background for my art piece. Like treasured artifacts, these remains of the boats held the story of hope. Kerstin Blomberg’s memory of the lighthouse at Färö became the very real possibility of how 7-year-old Hele was carried to shore by the man wearing water-waders.

Central to my art is the metaphor of change… a ship’s spinner. It represents Hele’s past – of her mariner grandfather kapten Sillaots, of the escape boat that had stopped at sea and circled in the wrong direction but then miraculously continued on route to Sweden, and eventually in the new direction to Canada. Then the image of Hele, carried and cared for in Pärnu by Heido and looking in the garden for luck with acknowledgment of the lilac petals. Relatives such as Onu Märt Laarman with the imprint of his woodcut of a young girl daydreaming by oak trees represents my mother’s life-long thoughts of love and correspondence with her father. Juhan Viiding, a distant cousin and well-known poet, has the words of “Kus on kodu” in the song “Kodulaul”, questioning the yearning feelings of home for Hella and Hele. The ferns and oak leaves suggest the fields where the connections of Estonia, Gotland and Färö meet. The lighthouse symbolizes the light that brought the boat to safety and the optimism and love of Heido that brought Hele the luck she needed with her courageous mother Hella to cross the stormy sea “into the unknown”.