There are places named after the nation itself. The humble Lac Estonie is surrounded by forested land in Matawinie Regional County Municipality. Ice climbers can ascend a route named “Tallin” [sic] in Saint-Donat, Québec. There are even roads with names that look like they could have been chosen by a mischievous Estonian city councillor: for example, Nina Street and Keele Street in Toronto. But this is just a tongue-in-cheek observation.

You have to dig a lot deeper to find a place in Canada that's named after an Estonian person. Here are a few you might not have considered:

Andy Olvet Lane, Toronto:

It's a rather unassuming corner of Toronto, lined with leafy green vines, brick and wood homes, back yards, and small garages. For Andres “Andy” Olvet, though, it was a part of his home neighbourhood, The Beaches. Here, a Toronto street sign, in the newer style with a rounded top, bears his name for all to see.

In May 2018, Signal Toronto reported that this laneway was to be named after Olvet, with former City Councillor Mary-Margaret McMahon speaking highly of his impact on the community. Professionally, Olvet was a managing partner at the law firm Bigelow Hendy LLP.

Olvet had a passion for hockey, folk dancing, tennis, and football, the latter of which he won numerous trophies for. As a swimmer, he was known to swim across the shore of Lake Ontario from his home to reach, of all places, the local swimming pool.

Having lived in the neighbourhood since he immigrated to Canada in the early 50s, he was an active presence in local recreational spaces such as Kew Gardens Tennis Club. McMahon added that “He was very much loved in the community.”

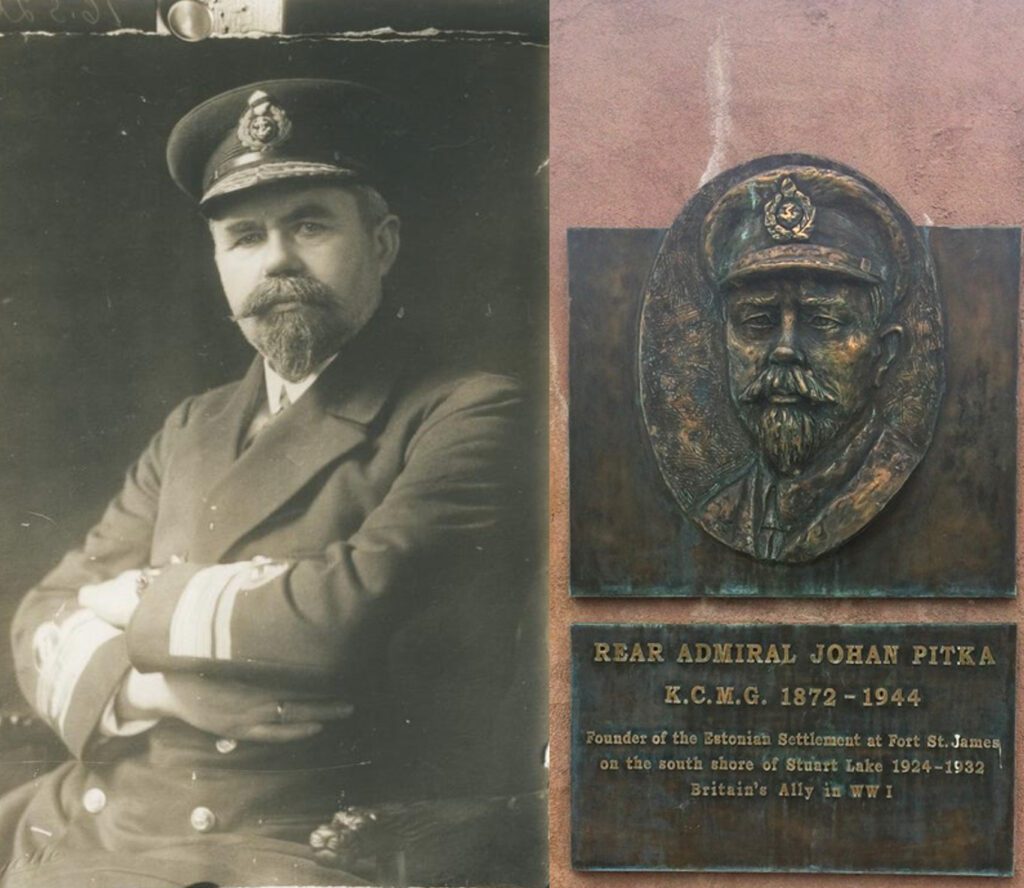

Johan Pitka Memorial, Fort St. James, British Columbia:

Seven years after a monument was unveiled in his honour in Tallinn, Johan Pitka—one of the founders of the Estonian Defence League and a Rear Admiral of the Estonian Navy during the Estonian War of Independence—was the subject of a second monument in interior British Columbia. At Spirit Square, the main park of Fort St. James, the Society for the Advancement of Estonian Studies in Canada installed a bronze bas-relief sculpture, created by sculptor Aivar Simson and architect Emil Urbel. It depicts Pitka from his shoulders up, wearing his peaked cap. The front of the memorial reads “Founder of the Estonian Settlement at Fort St. James on the south shore of Stuart Lake 1924-1932… Britain's Ally in WWI.” Below this text is a small ship's propeller. In a 1991 issue of the Canadian Ethnic Studies journal, Juta Kõvamees Kitching writes of how Pitka, subsequent to being knighted in Britain in 1920, heard about the prospect of available land in BC for homesteading and attempted settle with his family on the southern shore of Stuart Lake. They went along with three other Estonian families, three couples, and seven men. Kitching describes how they “struggled against the wilderness for eight years; they tried cattle-raising, farming and lumbering. However, markets were lacking and transportation was difficult without a road.” He eventually decided to return to Estonia, along with his family, where he disappeared in 1944. Johan's wife Mari-Helene Pitka and their daughters Linda and Saima permanently returned to BC in 1948. From the park, you can see Stuart Lake stretch 66 kilometres westward. On the south side of the lake is Pitka Bay, the home of a fishing resort. Flowing into the bay is Pitka Creek. In the vicinity is “Lind[a] Lake” (named after Johan's daughter) and “Paarens Beach Provincial Park” (named after Johan's son-in-law). Just 45 klicks south of here is Pitka Mountain, with an elevation of 1,386 metres.

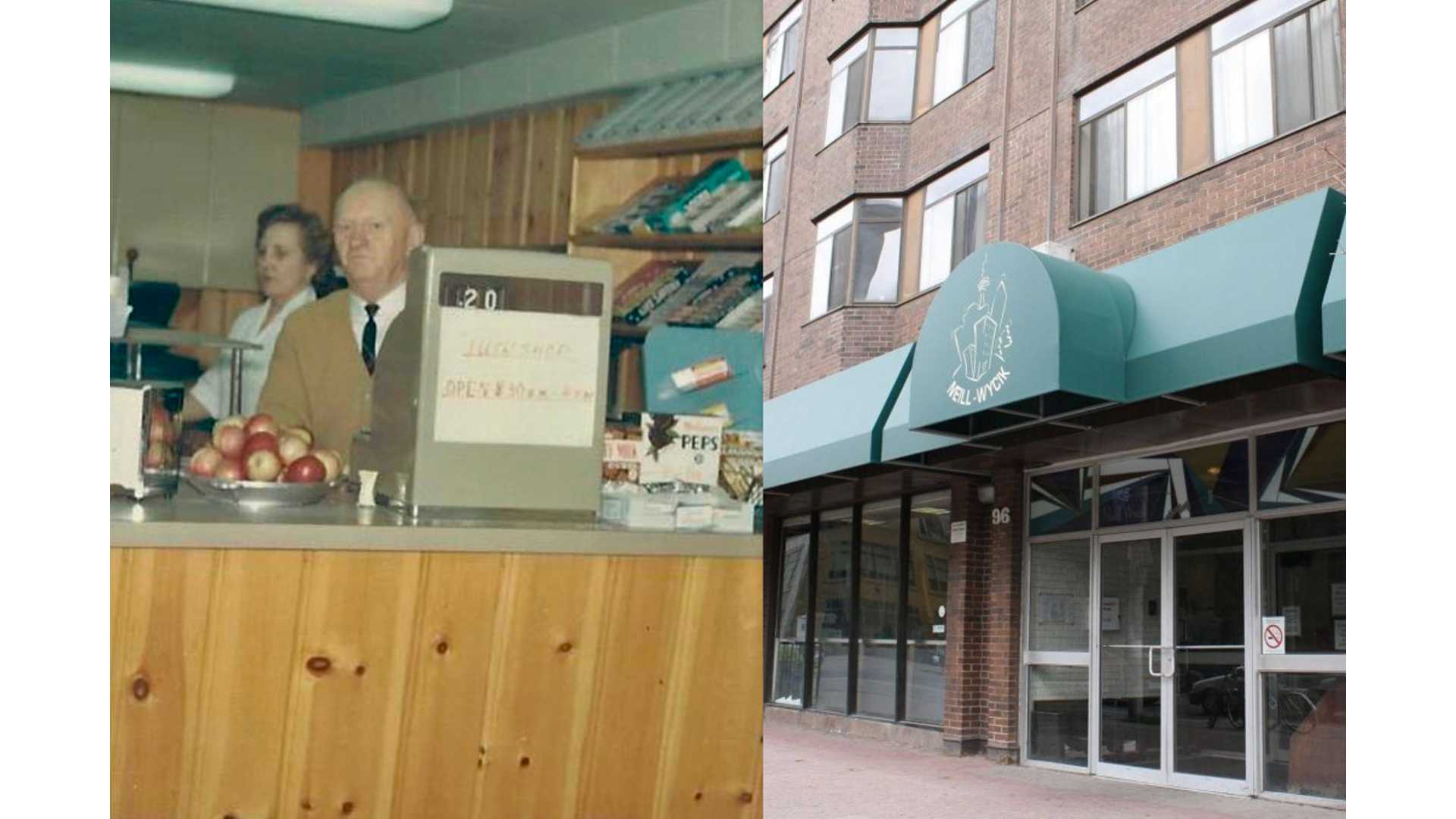

Neill-Wycik Co-operative College, Toronto:

At 96 Gerrard Street East, a tribute to a couple with a connection to Toronto's Estonian legacy goes under the radar for most passersby. But for everyone who was aquainted with Aurelie and Raymond Wycik, at what was then the Ryerson Institute of Technology, the Wycik name has warm connotations.

The couple, known affectionately as “Mama and Papa Wycik”, ran a tuck shop called the Ram's Corral for students, starting in 1950 and operating for more than 25 years. The Ram's Corral's first location was the old student's union building; but in 1960, it was relocated to the basement of Oakham House, a 19th century brick building at the intersection of Church and Gould. The Wyciks also operated a cafeteria and a men's residence hall in the same building.

Reet Oolup, Secretary of the Tartu College Executive Committee, remembers “I knew both Mama and Papa Wycik quite well as my mother worked for them for a number of years… Eggy the Ram (the schools' mascot) was [housed] in a corral behind the building where [Raymond and Aurelie] last worked. They also looked after the ram.”

Aurelie (née Grossberg) was from Tartu and Raymond Wycik was Polish. Raymond was Aurelie's second husband, whom she met in England after having fled Estonia in 1944. According to Surbhi Bir of Toronto Met University Magazine (formerly Ryerson University Magazine) when the Wyciks emigrated to Canada, “Mama came to Ryerson hoping to take English language courses, but instead took up a job at the tuck shop…”

This contact was fateful, as the Wyciks became very popular with the many students who frequented the place, and, as Toronto Business Daily notes “Aurelie also helped fellow Estonian refugees secure custodial jobs on campus,” expanding their kindness beyond the students.

A four minute walk away from Oakham House, Tampõld Wells Architects' design for a student co-op residence was built, opened for residents in 1970. Aurelie passed away in 1978 and Raymond passed away in 1989, but in recognition of their hospitality, a group of students had decided to partially name the residence after them.

*** Perhaps the rarity of places named after Estonians is a commentary on the character of Estonians: that they generally don't wish to draw too much attention to themselves, or that they'd rather let their actions speak for themselves. If an Estonian person's name is on something, it was likely applied by someone else who was fond of them. The challenge is yours now, dear reader. Let us know of other places you know of in North America that are named after Estonians.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.