The amorphous, overwhelmingly loud guitar effects (including reverb, echoes, and heavy distortion) create a wash of sound that buries atmospheric vocals. Meant to be accompanying melodies to the intimate fabric of noise, lyrics are often unintelligible, putting listeners in a hypnotic dream-like trance.

Shoegaze’s sound originated in the UK during the late 1980s and is inspired by a melting pot of earlier musical movements, including the psychedelia of the 1960s, 1970s post-punk, and 1980s American noise rock. Bands like The Jesus and Mary Chain and the Cocteau Twins extracted different elements of these movements to create a unique soundscape that influenced later shoegaze artists. The Cocteau Twins’ fourth-studio record Victorialand (1984), for instance, envelopes the listener in drowned out, angelic vocals and hazy guitar digressions. Meanwhile, The Jesus and Mary Chain used feedback in their 1985 record Psychocandy to create a resounding barrage of noise, perfectly balanced between chaos and harmony.

Just under a decade later, My Bloody Valentine released their critically-acclaimed 1991 record Loveless. The album is often cited as the pinnacle of the shoegaze genre, representing the true essence of its sound. Washed out swirls of stratospheric sound bid the listener to drown out the happenings around them. Shoegaze is not for socializing, it's for drifting away. It’s a sound for dreamers.

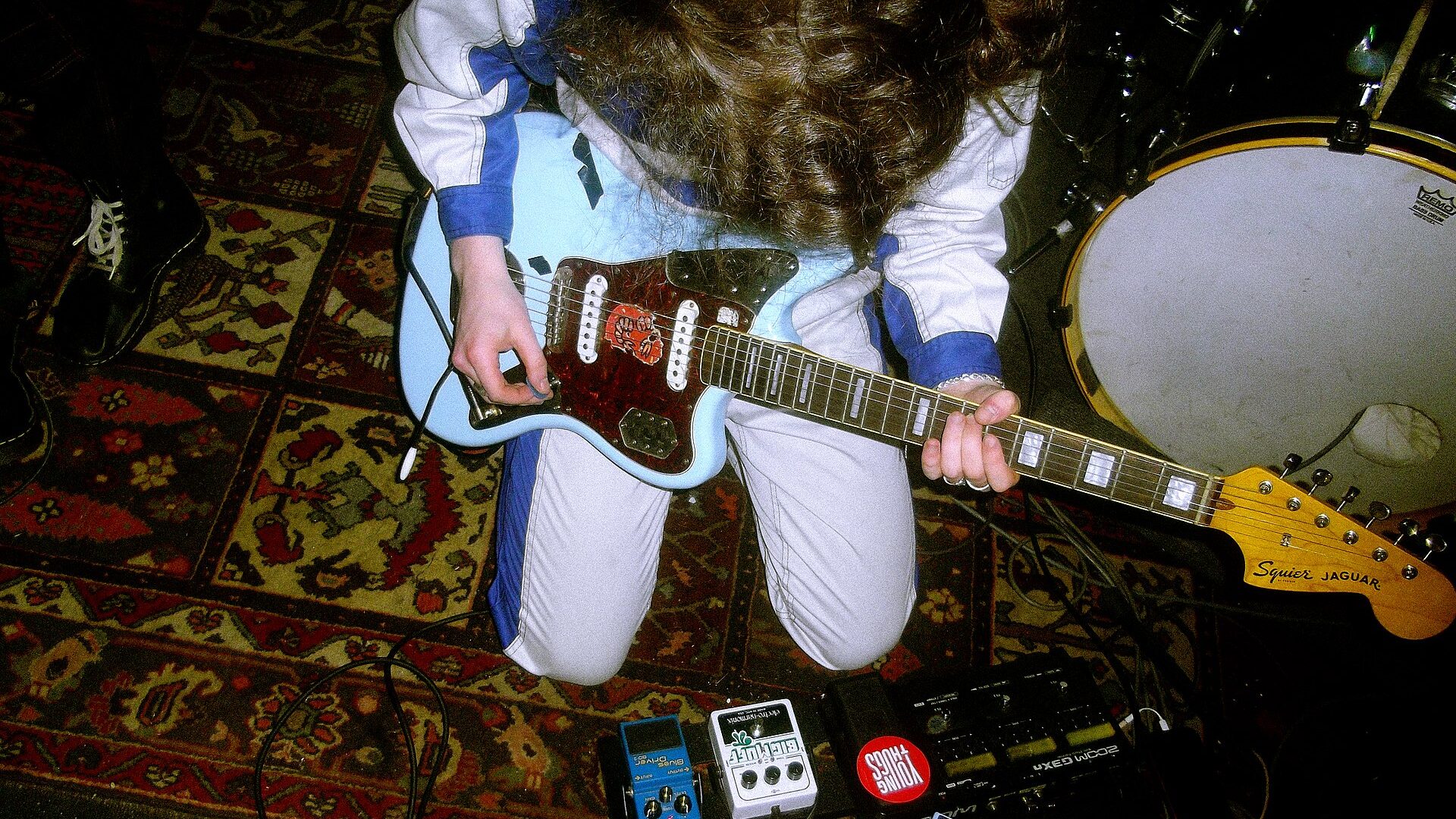

Maybe this detached form of listening is why British music critics originally gave shoegaze a bad rap. The term itself was used to describe how artists performed at shows. Rather than engaging with the crowd, performers glued their attention to the floor where their foot-activated guitar pedals lay. These were necessary for producing the guitar effects quintessential to shoegaze’s sound. But the British media coined “shoegazing” as something negative.

While most shoegaze bands were antagonized by the press, Slowdive was disproportionately so. In a review of Slowdive’s album Souvlaki (1993), Melody Maker’s Dave Sampson wrote that “This record is a soulless void. I would rather drown choking in a bath full of porridge than ever listen to it again.”

Perhaps critics like Sampson negatively perceived shoegazers’ aloofness because they thought these artists undermined the fundamental experience of live music: to witness an engaging stage presence. But shoegaze is not like ordinary live music. Nor is it meant to be.

Head-banging, crowd surfing, and smelling the sweaty stench of the stranger next to you are some of the joys that traditional rock concerts offer. But shoegaze concerts strayed far from this. Artists in this genre rejected commerciality and performance. Concerts, rather than being a display of grandiose theatrics, were meant to encase audiences under a serene wall of sound (a term developed by producer Phil Spector in the 1960s) that would drown out the chaos of everyday life.

“Likes attract likes,” wrote British magazine Underground. “The pre-occupied shoegazers on stage are playing for those who are just as coy as them. The mere desire of experiencing heavy distortion and feedback are all that matters. There is no need to be performative, as agreed by both the performers and the gig goers.”

Shoegaze, though widespread, was short-lived. The sudden emergence and growing popularity of Britpop and grunge squashed shoegaze’s relevance.

Since the late 2010s, however, there has been a resurgence of shoegaze’s popularity. According to Spotify, there were twice as many shoegaze recordings released (or released) in 2018 as there were in 1996. The same article reports that “while shoegaze started in the UK, today the music is streamed the most in Portugal, Greece, Israel, and Lithuania—and most modern shoegaze bands aren’t British, they’re American.”

Estonia also has a significant shoegaze scene.

Formed in 1998, Pia Fraus has released seven studio albums. Their 2002 record In Solarium offers the classic shoegaze sound with washed out (English language) vocals and fuzzy guitar riffs. But the record goes even further by incorporating elements of electronica similar to those of the Boards of Canada.

Although lesser known, She Bit Her Lip is just as deserving of praise. Their debut album <I>Viiv<I> (2015) features lyrics entirely in Estonian. Far from being heavy on the guitar feedback like The Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy, Viiv offers a soothing and weightless listening experience.

Lastly, Bizarre’s 1994 album Beautica is certainly an unpolished gem in the shoegaze scene. Out of the three mentioned, Beautica is the most atmospheric. Dreamy, drowned out vocals sound as if they are trapped in a bottle effortlessly floating through the ocean waves.

So what can explain the world’s sudden renewed obsession with the shoegaze scene? Trends come and go around. That has been made clear by the fashion industry. The same is true with music. It was only a matter of time before something popular in the 90s would return to its former glory. But perhaps this explanation is too simplistic.

In an age where many are chronically online, we find ourselves trapped in a world defined by sameness. At best, hyper consumerism has limited trend cycles to last a few months. Social media fuels constant competition to buy the latest craze. People who blindly follow these micro trends are deemed “basic” or unoriginal. (This is not to say that enjoying mainstream things is bad – just that the term is often used condescendingly.) Others feel a strong need to differentiate themselves from this alleged insult. This has manifested in the form of reviving trends once enjoyed by the oddballs and nonconformists of the past, including shoegaze enjoyers and performers.

Shoegaze has stood the test of time. Whether its sudden revival amongst young people can be attributed to trend cycles or something deeper, shoegaze remains good in its own right.

This article was written by Natalie Jenkins as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.