About Brigitta Davidjants: Brigitta Davidjants is a researcher at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre who has primarily focused on Estonian pop culture. Her main research interest is how subcultural organization occurred during the transition from late socialism to a post-communist society. Earlier, she researched the construction of Armenian national ideologies. She has also published fiction and has been a long-time journalist.

About Stephen Perry: Stephen is a second-generation Estonian. Stephen works with a publishing team called UXP press and they have just released a book called He Hijacked My Brain: Gary Topp’s Toronto. Stephen also has forty years of experience in radio broadcasting.

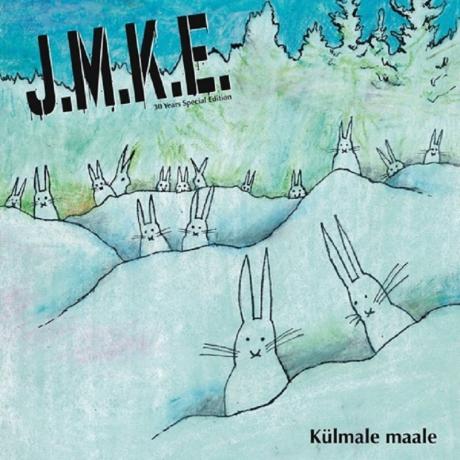

Stephen had the opportunity to speak with Brigitta on Saturday February 1st, 2025. Brigitta is the author of a new book on punk rock band J.M.K.E., titled J.M.K.E.’s To the Cold Land. The conversation below was recorded for CIUT (click here for the episode) and will air on Sunday February 16th, 2025 at 10:00 p.m. EST (tune into 89.5 FM or at www.ciut.fm — you can view all episodes of the show, Equalizing Distort, by clicking here).

Stephen Perry: Who is J.M.K.E. and why are they important?

Brigitta Davidjants: J.M.K.E. is an Estonian hardcore punk band who played their first concert in 1986. In the local punk scene, they are legendary and continue to be embraced by all generations. Go to one of their concerts today and you’ll see both sixty-year-olds and twelve-year-olds singing along, regardless of gender identity or social background.

Punk was perfect for this moment in history—not only musically, but also lyrically. The words were self-ironic, humorous, conversational, and intricately crafted, making them both powerful and timeless.

(Brigitta Davidjants)

There are many reasons for their enduring impact, but what really sets them apart is their ability to capture the prevailing mood of society. Their 1989 album To The Cold Land, in particular, reflects the emotions of Estonians during the collapse of the Soviet Union, as the country transitioned from perestroika to freedom. At the beginning of the decade, punks were persecuted by the militia, but during perestroika they were suddenly elevated. This album–especially the song “Hello Perestroika”—became the soundtrack of the era, with lyrics that people knew by heart.

The track list itself forms a poetic narrative, moving from Stalinism to perestroika. The songs deal with the themes of Stalinist crimes, stagnation, and skepticism about perestroika and change. At the same time, they serve as anarchist-pacifist protests. Punk was perfect for this moment in history—not only musically, but also lyrically. The words were self-ironic, humorous, conversational, and intricately crafted, making them both powerful and timeless.

SP: Why is this album still so important?

BD: That's a good question. When I started writing the book, I knew why the album was important to me. But I also knew it was important to a lot of other people. So when I was working on the final chapter, I decided to ask people why they loved it. I posted the question on Facebook. The post was widely shared and I ended up talking to boys and girls aged eleven to thirteen, men in their fifties, and people in their thirties and forties.

Three main narratives emerged from these conversations. First, for the older generation who experienced the release of the album in real time, it was a powerful statement against the Soviet occupation. It captured the emotions and resistance of the time. Secondly, for the youth of the 1990s, myself included, the album had an educational aspect. At a time when school and teachers were boring, or when history lessons were too national-romantic for a cynical post-Soviet generation, this record offered an alternative way of understanding Estonia’s recent communist past. And today’s kids see it as an anarchist-pacifist manifesto—an anti-war and anti-climate catastrophe statement. And of course, we all appreciate the incredible music. But what really amazed me was how the album brought together people from very different backgrounds—anti-fascist punks as well as those with right-wing leanings. Yet they all shared the same abstract feeling: that the music was confronting evil, even if what was understood as “evil” depended on the listener. For some it was communism and totalitarianism, for others it was the destruction of the planet or the sacrifice of human life for a so-called noble idea.

SP: Can you tell me about the song “Minister ei tea mu nime”?

BD: This song has a really interesting history. At the time it was written, all men in the Soviet Union, including Estonians, were afraid of being sent to war in Afghanistan. There was also a huge fear of the atomic bomb, because both sides were reinforcing the idea that a nuclear war could start at any minute. Here in Soviet Estonia, this aggressive struggle for peace was at the heart of the propaganda. Basically it was that we needed the atomic bomb to have peace. But for the people, all this talk about peace sounded completely hollow, because we had suffered at the hands of these powers, for example when our families were deported to Siberia during the Stalinist regime.

… it reflects the contradiction between official rhetoric and reality in the Soviet Union, bringing together the forced militarism, the nuclear threat, and the anarchist-pacifist rejection of official policy. It is also lyrically very complex, with singer Villu Tamme singing from very different positions…

(Brigitta Davidjants)

This song takes a clear anarchist-pacifist stand. [The title] means “They don’t know my name” and it reflects the contradiction between official rhetoric and reality in the Soviet Union, bringing together the forced militarism, the nuclear threat, and the anarchist-pacifist rejection of official policy. It is also lyrically very complex, with singer Villu Tamme singing from very different positions—he parodies forced militarism while musically using melodies reminiscent of the [Young Pioneers] songs of the time. But then he changes the melody in such a way that it sounds somehow terrifying—only to suddenly become a poetic spectator. For example, when he sings “Don’t call me, I’m not in today. I locked up, went to see the battle,” he distances himself from participating in the conflict.

And when a [Pioneer-style] jumpy melody is replaced by a [military] marching beat, he subtly introduces the fear of [a] nuclear threat, which combines all fears into one: “My initials are now flashing in the haze of nuclear winter / But the minister and the general won’t know what they are.” And at one point, the irony ends and the real feeling of pity begins: “That wind, that silence, those colours—what a miracle! So beautiful is death and so stunning is the raped country / Pity they ever know my name, Nobody will ever know my name.”

SP: Can you tell me about this book titled J.M.K.E. To the Cold Land?

BD: Well, basically, it’s a book in a series called 33 1/3 Europe, published by Bloomsbury, that tells the story of a particular album. This book is about an album by the Estonian punk band J.M.K.E., a band I've loved since I was twelve or thirteen. Their name is an acronym from Jaroslav Hašek's book The Good Soldier Švejk—Jeesus Maria karjatas eit—which translates to “Jesus Maria, the broad screamed”.

SP: Does the publishing company just focus on books about albums?

BD: In fact, Bloomsbury is a fairly large publishing house that publishes fiction, academic books, etc. There have been some very interesting books in the series… starting with Kate Bush and ending with Joy Division. I also know that they have books about Canadian musicians, starting with Céline Dion and k.d. lang and ending with Joni Mitchell. But probably the most famous book [series] published by Bloomsbury was Harry Potter!

SP: Can you tell me about the song “Käed üles, Virumaa”?

BD: Villu Tamme’s music has always been characterized by a strong green political ethos, even in the 1980s, and the song “Hands Up, Virumaa” reflects this. In the USSR, with a green mindset, everything appeared fine on paper. At the same time, many destructive projects were underway, such as the diversion of Siberian rivers. The 1980s saw the rise of non-state environmental movements in many parts of the Soviet Union, closely linked to political activism. National goals and the desire to protect the environment became symbiotic. This song also addresses the environmental threat in Estonia, known as the Phosphorite War—a wave of protest that began in the winter of 1987 and reached its peak the following spring, in response to the establishment of phosphorite mines by Moscow. Today, the Phosphorite War is often portrayed as the first stage in the regaining of independence. However, it was not only a fundamental struggle for freedom but also a clear response to a potential ecological threat. Estonians also had developed a strong sense of themselves as a people of nature—and we still go mushrooming in the autumn and berry-picking in the summer.

…he reflects on the fear of foreign powers by weaving it into the motif of the cuckoo, the most popular bird in Estonian folk religion. The cuckoo is also known as a bird of ill omen. If it sings near a person’s home, it signifies that someone will die, fall seriously ill, or suffer a fatal accident.

(Brigitta Davidjants)

All these developments were reflected in real time in this song. The song encapsulated Estonian identity politics, resonating with the self-image of Estonians as a Finno-Ugric people connected to nature. It also reflected the author’s concern about potential environmental catastrophes. The song combines several perspectives. From a lyrical standpoint, the author does not resort to clowning or irony but speaks openly about the issue that concerns him. The lyrics blend directness with poetic self-expression. In the first verse, for example, he reflects on the fear of foreign powers by weaving it into the motif of the cuckoo, the most popular bird in Estonian folk religion. The cuckoo is also known as a bird of ill omen. If it sings near a person’s home, it signifies that someone will die, fall seriously ill, or suffer a fatal accident. The song then shifts to the perspective of the resident, a position supported by the melody and arrangement, and then returns to the first person, speaking once again from the viewpoint of an Estonian striving to protect nature. I believe this is what makes the song so powerful.

SP: Can you situate this album for us by telling us a little bit about Estonia at the time?

BD: Well, that was the time of the revolution in Estonia—and this is the soundtrack to it, a pretty cool one in my opinion.

SP: Can you tell me about the significance of the title To the Cold Land

BD: The title To the Cold Land embodies the deep sense of skepticism and fear that Estonians felt during the period of Gorbachev’s reforms in the late 1980s. While the Soviet Union’s political landscape appeared to be shifting with increased freedom and openness, Estonians remained wary of the resurgence of Stalinist policies and the possibility of a return to harsh Soviet control. The song reflects this uncertainty, using the metaphor of a “cold land” to allude to the historical trauma of Soviet deportations of Estonians to Siberia.

The quickening pace of the song and its chilling refrain are a direct response to the haunting memory of the forced resettlements and the persistent threat of returning to such brutal conditions. Beyond the political and historical context, the song also connects to deeper layers of Estonian identity and memory. Drawing inspiration from Eduard Vilde’s novel To the Cold Land from the end of the 19th Century, the song references the long history of Estonians being sent to Siberia, already [taking place during the era of the] Russian Empire.

SP: What were some of the other themes on this record discussed in the songs?

BD: The album offers a poetic narrative of historical events in Estonian 20th Century history. Songs such as “My Grandfather Was a Deserter”, “Beria is Still Alive” and “To the Cold Land” reflect on the Stalinist era, focusing on the traumas of the 1940s and 1950s, including the war and Stalinist crimes. The period of stagnation leading up to the 1980s, marked by censorship, Russification, and economic decline, is explored in songs such as “Censor” and “Psychiatry is Helping Us”, which deal with the suppression of creativity and dissent and using psychiatry as an instrument to punish. Other tracks such as “Hello Perestroika”, “Hands Up, Virumaa” and “Internazis” deal with the changes and challenges of the perestroika era, from skepticism about Soviet reforms to resistance to environmental and cultural threats.

In addition to specific historical events, the album also delves into ideological and existential concerns, with songs criticising Soviet power and expressing anarchist-pacifist sentiments. Tracks such as “They Don't Know My Name” and “Summer of the White Butterfly” reflect the pervasive fear of nuclear war which haunted the Soviet people at the time, often laced with irony and sardonic humour.

SP: How can we get this book?

BD: The book can be ordered from the Bloomsbury website and from other major bookshops.

SP: There is a hit on this record. The song “Tere Perestroika”. Can you tell us about it? Why is it significant? Why did it become so important?

BD: “Hello Perestroika” captured the skepticism surrounding Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms, even amidst the excitement and hope. Initially, the song seems to offer enthusiastic support for perestroika and the promise of democracy, with its utterly optimistic tone. However, the deeper layers of the song subtly critique the reality of life in the Soviet Union—a reality marked by dictatorship, censorship, and violence for many decades. The irony is clear: while the public was urged to embrace a new beginning, the song’s underlying message questioned whether perestroika was genuine or merely a façade. This ambiguity resonated with Estonians, who were both hopeful and cautious about the future. “Tere Perestroika” became important not only because of its bold critique of the Soviet regime but also due to its widespread appeal. It became an unofficial anthem for people, who felt a deep connection to its message of skepticism.

By the way, there are actually two versions of the song: the first, softer, and the second, rockier. Initially, Villu Tamme performed the song alone as an interlude at some concerts, but as the song gained popularity, a version with a lighter arrangement was also recorded. Later, a full-volume punk version was created, but according to Tamme, such an approach didn’t fully justify itself: “It didn’t fit at all with the idea of a naive person aspiring to a happy future. In this song, I was a naive person, trying to sing a happy song with a happy face and a soft voice. I played a person who sincerely believes that a happy future has arrived. The song was also musically naive, playing single notes with the simplest rhythm in the world, as if it were the first tune the person was singing—as if, for the first time in his life, he felt the need to pick up a guitar because life in the Soviet Union had suddenly become so beautiful.”