What makes poetry so universal is its ability to distill a person's essence and ideas. Proof of this is in the work of Estonian-Canadian poet and artist Jaak Viirland.

Viirland's personality is passionate and spirited. He has a wry sense of humour. And he is a curator of memories.

These qualities can be perceived at a country property of his, on which he owns a few sheds. One of these is painted blue, black, and white, and the others are decorated with artwork made from found objects, such as machine parts.

Relics of his past and his interests line the interior of the blue, black, and white shed, a 20 x 30 structure. There's a Triumph TR2, a silver convertible with a red rag top. Surrounding this elegant automobile is a big map of Estonia, more of Viirland's artwork, paint, tools, and varnish. Sitting in this space with a wood-burning stove crackling away, he tells me on the other side of the phone line, “It brings back memories of my father, because we built all of this.”

It's through this type of reflection and remembering that he has pursued poetry.

For Viirland, the impetus to write came in his teenage years, followed by the start of his job at Stelco, a steel company. He was going to coffeehouses in his off-time, thinking, observing, and building up to a wave of poems that would sweep through in the 60s. In these poems, we get a sense of a fiery, passionate young man who is questioning the world. Take, for example, “The Bridge”, from 1966. Here, Viirland turns a bridge into a symbol for an inevitable life struggle, something that “lies in your path”, that “has to be crossed”, but at the same time creates “a feeling of inadequacy.” He ends the poem by questioning the bridge's existence and calling on readers to tear it down.

In the 70s, his tone became more tranquil, which brought out the poem he is most proud of, “Stones in Water (For Markus).” Written in 1974 for his two-year-old son, it depicts a walk by a little creek near Viirland's home in Burlington, where they threw stones in the water for fun. He captures a father's rediscovery of simple pleasures in the lines:

“With evening here and sleep at hand/ An hour to spend on brookside land/ A stone to throw/ A splash to see/ How it thrills a two-year-old me… The air is cool/ The day was long/ My heart is happy/ My mouth full of song/ The daylight dims we move along”

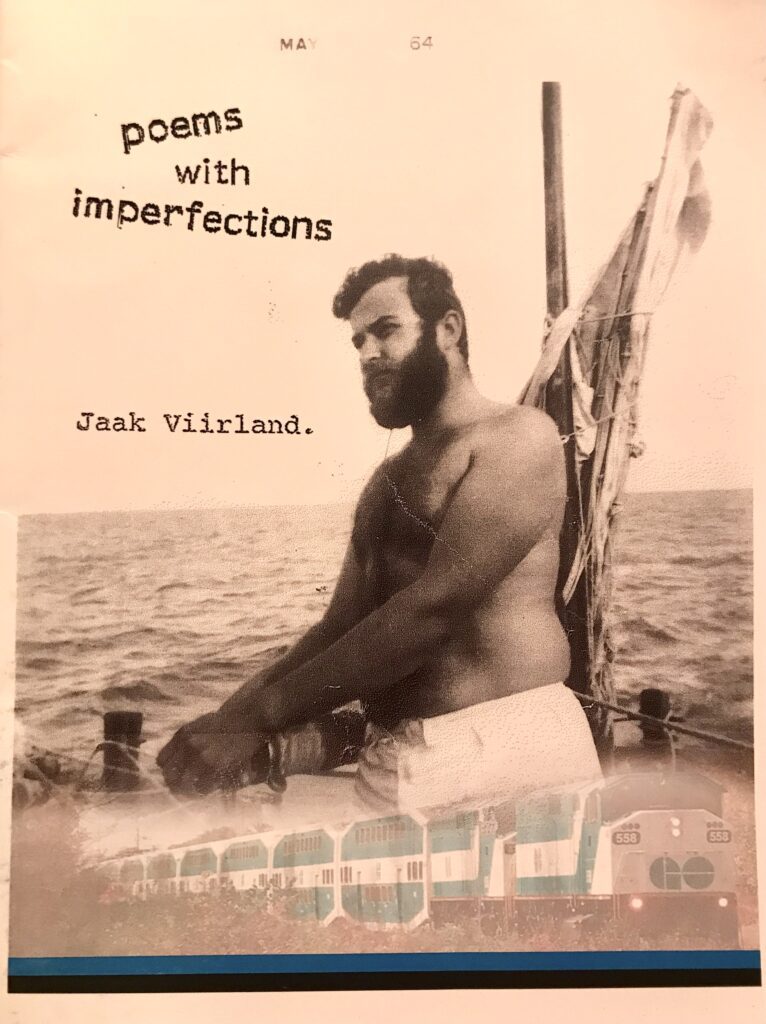

When the 80s came around, he mixed together that initial questioning with more humour and sarcasm. In the first and fifth stanzas of “Destination Toronto. GO Train Yourself.” from 1982, he laments the lack of human interaction on public transit that he took every day from Burlington to Toronto.

“I have direction from my master,/ I'll try to avoid the worst disaster/ Moving along with the greatest of care,/I soon will find that I'll be there./ I'll GO train myself to my destination… ‘Twould be so nice to see reaction,/Friendly ones with some distractions…./Smiles and laughter all abounding, each time it stops for boarding to their destination.”

The source of stylistic changes in each of these periods encompasses his passing through the education process, starting a family, and time abroad.

Back in 1964, at the encouragement of his sister, Viirland left his job at Stelco and travelled down to Florida, where he began sailing around Biscayne Bay in his friends' Chinese junk ship. The vessel, named Golden Dragon, was made in Hong Kong and then shipped by freighter to the US. On one hand, many parties were thrown on the ship, such that the Coast Guard called it “the floating snake pit.” But there was hard work for Viirland to do in between. He recalls, “I slept on board, moored at Coconut Grove Marina, for a few months while going to the University of Miami.” In between studying, he worked odd jobs in the geology department, painted offices, and did roofing to pay for his tuition. After three years, he graduated cum laude. And eventually, the nine and a half ton teak ship sank.

When it came down to writing, poetry was something that was fuelled by the right mood and the act of, as he puts it, “trying to find myself… In those little lines, I was going down many different avenues. I met people, I came back home, and I wrote about it all.” Among these influential people are Estonian poet Doris Kareva and Canadian painter Helen DeSilaghi.

These days, he has been contributing to the local community of Estonian artists. EKKT (the Society of Estonian Artists in Toronto) President and friend Elva Palo notes, “Jaak is officially a Supporting Member for EKKT and he specifically sought out our group [in 2019] because of his interest in art and artists from an Estonian heritage…”

Palo says that Viirland “has sent videos of Estonian musicians, writers and poets. In our newsletters I have shared his interests with the rest of our membership. EKKT truly values all of our Supporting Members as they share with us a sincere interest in seeing our Estonian community cultivate all sides of creative experiences.”

Palo also remarks on the “almost archeological” feeling of his artwork, where objects “relate to a history of purpose and are newly juxtaposed to evoke conversation.” In the end, both visual art and poetry tell the story of his life.

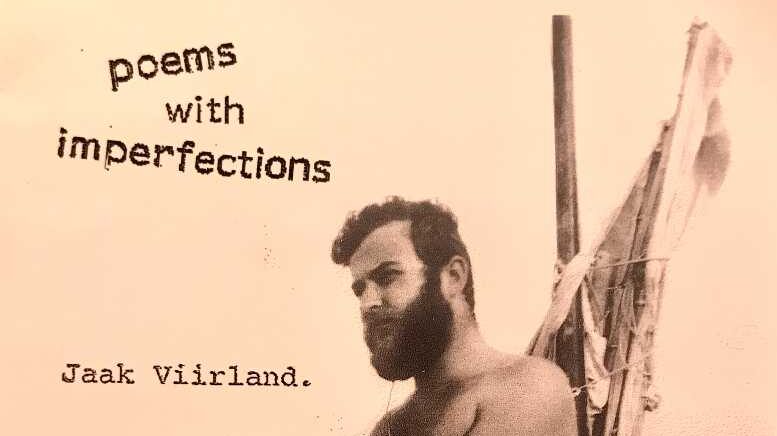

Viirland has not written poetry in many years, but has printed small runs of two collections of poetry with the Burlington-based company Eagle Press: Poems With Imperfections and Poems With More Imperfections. The latter booklet features scanned handwritten manuscripts of his poems, including ones that don't appear in the former booklet. Other poems haven't been put into book form.

The booklets are never sold, but are given out from time to time, including copies that have been sent to the VEMU archive.

With the titles of these booklets, I asked Viirland if he deliberately sought imperfection, or if he was merely being humble about his creations. He says, “I feel I'm imperfect. And I guess it was an outlet for me. You know, to just express myself… I just did it for a sense of satisfaction.”

We can add one more appealing reason to write poetry: it will always succeed in soothing one's soul.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.