As the years have gone by, I have started appreciating Estonian-ness more and more: Not babbling about anything and everything, not being so direct, but caring more about the interlocutor. Never mind that we are in an era where talking about your nationality or pride in it hardly endears you to a lot of people.

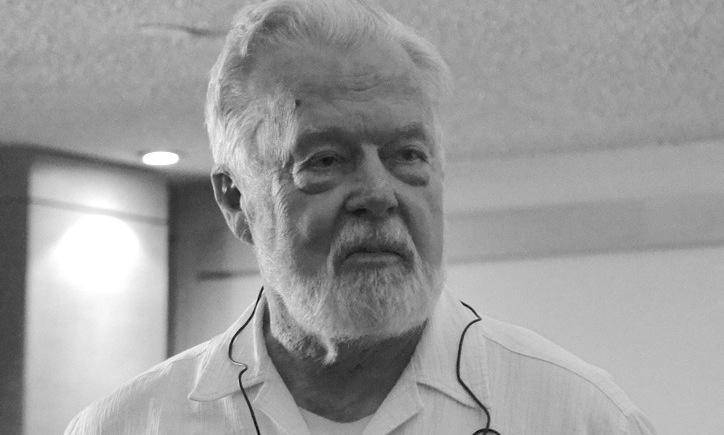

With Vello Salo, I got two strong senses at the same time: A Spiritual sense on the one hand, but also a sense of being connected to a spiritual Estonian-ness, which hopefully I will carry with me till the day I die. This is because Father Vello's spirituality came from serving, and his Estonian-ness was very deep-rooted, running a lot deeper than mere nationality of a particular state.

Father Vello himself repeatedly stated that it is difficult for an Estonian to be a servant. From early on in its history, the ”under-people” tag has not lent itself to helpfulness or openness, and has also made Estonian history sensitive to class distinctions. In this way, Father Vello was something of an expositor and excavator of atavistic and ancestral behaviours.

One of his most endearing traits was reflected in many of his honrouable actions. Having a broad experience of different, and not so different, cultures and civilisations, without doubt exceeding even those of (exiled Estonian writer) Karl Ristikivi, Father Vello had a much greater opportunity to spread his story worldwide and to serve his own people, still shackled at that time. Serving as a Roman Catholic priest during the cold War gave a broad canvas which he could express himself on.

Naturally, his fame preceded him. I first came across him on the Voice of America broadcasts, with Ilmar Mikiver, then towards the end of the last century, at the Pater Noster church on Jerusalem's Mount of Olives, where he signed off his ”Our Father” prayer with an ”Estonians in a Free World”.

Finally I got to meet him for the first time, thanks to another Estonian Catholic priest, now serving in Germany, Father Rein Õunapuu.

I was able to talk to Vello Salo about those things which had a backdrop we both understood – things which I could not talk to anyone else about. I also had the opportunity to travel and experience other cultures, and could freely share much of those stories with Father Vello. However, we always have to apply a spiritual approach, in our case, and naturally cultural and societal themes follow on.

Sometimes we had a laugh together that priests have so much to converse to the world about, but in practice they tend to keep this in-house, as it were. The world does want a different narrative, after all.

Father Vello was well versed in Orthodox traditions. Goodness, he'd even sing in the choir at our Orthodox church. I too don't take the trading off with Western Christian traditions lightly, and sometimes sing in the choir at the Catholic Church. And so we also conversed on the emergence of an Estonian spirituality, its bearing, contemporary perception and future developments. And the beautiful Estonian language! This was always on our lips…

Father Vello's humour was graceful, timeless, but at the same time an intriguing faculty. No (character from The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek) Otto Katz-esque clichés for him. He would have made a great politician. He had this talent to humorously deflect an uncomfortable, unnecessary or impolite aspect to a conversation. At the same time, how many were there who could read Father Vello's inner tears, when during some painful story, he had to still remain supportive, while at the same time he was screaming and crying towards the heavens…

For Father Vello, in my estimation, the number one thing in his life was Christ. And then people. And then Estonia – in that order. Sleep well, Father!

—