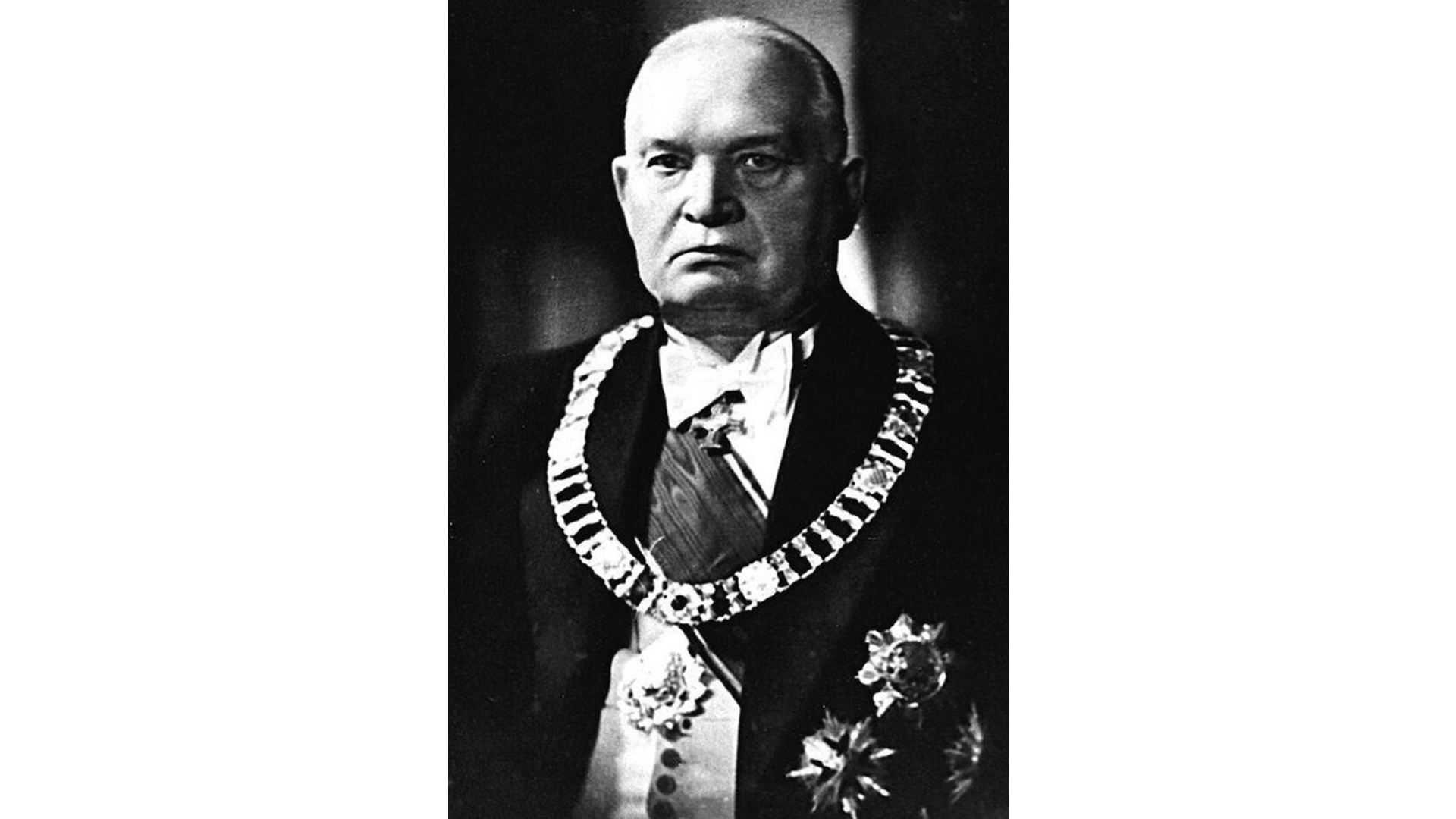

Growing up in Toronto, there was no figure in Estonian history that loomed larger than President Konstantin Päts. He was either President, Prime Minister, or Head of State of Estonia three times, and the sole President from 1938 to June 1940. A large painting of him hung front and centre in the main entrance of the Estonian House on Broadview Avenue, Toronto, and a large framed photograph of him hangs in a place of honour at Ehatare Retirement and Nursing Home in a suburb of Toronto. For our parents and grandparents, he represented the childhood memories of being surrounded by loving relatives and parents, living in an increasingly prosperous Estonia, and a world where everyone seemed honest and upright. And all of this came crashing down with the Soviet Union occupying the first Republic of Estonia. Päts' reputation was very clear.

While building Estonians houses (Eesti majad), Estonian schools, and churches around the world, diaspora Estonians felt that they were continuing in the spirit of Estonia, whose spiritual leader remained Konstantin Päts.

When I had been in re-independent Estonia for a few years and returned to visit my parents for Christmas, I remarked that there had been discussion in Estonia if Konstantin Päts had been a dictator during the period from 1934 to 1938. My mother took offense and yelled “How dare they say that. When I was a little girl, the President's car drove by and we showered him with flowers.” Emotions on this topic are still very strong.

And then the huge statue (seen in the photo above) of Konstantin Päts was unveiled in the very centre of Tallinn a few weeks ago. All should be well. But it is not.

Estonia obtained re-independence in August 1991… and then it took 30 years for a statue remembering Konstatin Päts to be put up in a public square in Tallinn. Why did it take so long? Why was not a single minister or Prime Minister present at the unveiling of the huge head („Riigipea“ in Estonian, Head of State—get it?).

If that was not bad enough, current President Alar Karis, in his remarks at the unveiling of the statue, stated “And of course the pitch black years of 1939 and 1940, with the occupation and annexation of Estonia, when Päts as President was under increasing pressure by the [Soviet] occupiers, he continually retreated.” My mother would have known what to call these last words: “HERESY!”

What was written about Päts by diaspora Estonians during the Soviet occupation is nicely summarized by Finnish historian Martti Turtola in his book President Konstantin Päts (p. 18):“ For foreign Estonian [publications between 1940-1970, there are] numerous works dealing with the life of Päts or memoirs of lives during the time Päts ruled. The large majority of them could be described as respectful, having admiration for Päts [or] perhaps even adoration. For foreign Estonians, Päts symbolized lost independent Estonia. He was the symbol of homesickness, a symbol of a lost fatherland. Analyzing or commenting on his choices or questioning his motives was tantamount to sacrilegious activity.”

It is conventional wisdom that there was no one more central and key in Estonia's fight for independence during the 1918-1920 period than Konstantin Päts. As Turtola states, “Konstantin Päts was the most important politician and statesman in Estonia.” Rein Taagepera, in his book 100 years of Estonian Politics states that (p. 148) “The central figure in Estonia's independence politics was Konstantin Päts.” More than any one individual, Päts was responsible for Estonia obtaining independence in the most trying of circumstances.

In 1934, Päts assumed dictatorial powers. The situation was no different in neighbouring Latvia and Lithuania. But it was during his authoritarian regime (the “Vaikiv ajastu” or the “Era of Silence”) that Estonia's economy prospered. Although the media was also censored, it is during this period that our parents and grandparents remember the “good old days” of Päts' Eesti. And the memory of the good old days is very powerful to this day.

For the first five years after re-independence, no Estonian historian dared to write about Päts and his role in the occupation of Estonia by the Soviet Union. And then appeared the Estonian historian Magnus Ilmjärv's book Silent Subjugation (Hääletu alistamine) which contained scandalous details that Päts apparently received regular payments from the Soviet Union's Embassy in Tallinn. Next came Martti Turtola's 2002 book President Konstantin Päts, which claimed, among other things, that moving to authoritarian rule in 1934 was at the very least illegal and led to many other questionable decisions later on. Turtola goes on to state that Päts always believed that it would be possible to work things out with the Soviet Union, like things were worked out in 1920. Many patriotic and nationalistic citizens found these claims to be offensive and many articles accused the authors of numerous ulterior motives.

Rein Taagepera's 2018 book 100 years of Estonian politics is very critical of Konstantin Päts, and states (page 51) that that the “Era of Silence” of authoritarian rule (1934-1938) gave rise to the subsequent silent subjugation of Estonia by the Soviet Union. Taagepera goes further and claims that of the choices faced by Päts in 1939, he made the worst possible choice for Estonia's future. Pages 56-64 of this book make for painful reading.

A more traditional view of Konstantin Päts and his era is found in the two-volume biography of Konstantin Päts by Estonian historians Toomas Karjahärm and Ago Pajur (published in 2018).

Signaling how complex the discussion surrounding the reputation of Konstantin Päts remains, Estonia's former President, Kersti Kaljulaid (2016-2021) has privately stated that the new Päts statue should never have come into existence.

Lauri Vahtre, an author of numerous historical books and an editor at the Estonian newspaper Postimees, wrote an opinion piece for the newspaper on October 20th, 2022 titled “Konstantin Päts is a major figure in Estonian history”, where he stated that we are reviewing the Estonian political decision of 1939-40 with 20-20 hindsight, and not based on the information that was known to Päts at the time. This view reflects the views of many people in Estonia today, who continue to view Päts with admiration and respect.

It is sometimes forgotten that the descendants of Konstantin Päts live and work in Estonia today. The grandson of Konstantin Päts, Matti Päts, was the Director-General of the Estonian Patent Office from 1992 to 2013. His son Madis Päts is an award-winning lawyer and Madis Päts' daughter Katariina is the President of the University of Tartu's Student Union. As the great-grandson of Konstantin Päts, Madis Päts was asked to share his views on how President Päts is viewed today:

“More generally, it is very difficult to analyze the activities of Konstantin Päts and his significance based on the books of Martti Turtola and Magnus Ilmjärv. The first has been widely regarded as a Russian ‘special operation', and the same doubts have been raised about the second. By the way, Ilmjärv's book, in reality, and for the most part, does not deal with the person of Konstantin Päts at all. The accusatory part of Konstantin Päts is in the introduction of the book, and its sources have been criticized a lot by Estonian historians. These authors are part of the trend, which was strongest during the first decade of this century, to claim to reveal the true nature of Konstantin Päts. These books claim to uncover the truth and to criticize Konstantin Päts (e.g. he bullied communists, patriots, freedom fighters from the War of Independence, etc., and finally sold off Estonia). In this short note, it is not possible to go into detail about their backgrounds, but among these critics are well-known Russian agents of influence as well as Estonian politicians who are trying to use certain historical facts for present-day political gain.

Should we not be asking ourselves, why did it take so long to erect this monument, and to which Konstantin Päts is it dedicated? In my opinion, K. Päts is attacked in modern times primarily in order to undermine Estonians' faith in our leaders today. The narrative that is often offered to us today is that K. Päts and his contemporaries were villains and betrayed you, and you cannot expect anything better from today's leaders either. A weak understanding of Estonian history has created a favorable background for all of this. The knowledge of the Estonian history of the 40-60-year-olds largely comes from Soviet-era journalism.

I have nothing against criticizing K. Päts. Most of this criticism, however, consists of malicious exaggeration or absurd claims. We cannot seriously discuss the fact that it is our own fault that we lost our statehood in 1940.”

It was well said by Martti Turtola in his 2002 book (p. 10) that “…it is up to an Estonian historian or academic to write a more thorough investigation of Konstantin Päts as a person and as a politician” (emphasis mine). Was this gauntlet picked up by historians Ago Pajur and Toomas Karjahärm in 2018? You, dear reader, can be the judge of that.

Reading so many contradictory views, it is difficult to come to a conclusion about the life and times of Konstantin Päts. But one thing is certain: discussing the legacy of Konstantin Päts will keep historians busy for many more years to come.