Although born in Chicago in 1958 and having grown up in Canada, Ardo Hansson has been Governor of the Bank of Estonia (the central bank), a member of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB—the second most powerful central bank in the world), and economic advisor to six Estonian Prime Ministers. But few people know his story.

Hansson’s parents left Estonia in 1944 and made their way to North America, where his parents met and married. They settled down in Chicago, where Hansson and his sister Anne were born. He did all the usual “Esto” things as a child: going to the Chicago Eesti Maja, eesti kool on weekends, Estonian church, etc. The family moved to British Columbia (just outside of Vancouver) in 1972, when Hansson was fourteen. The family was active in the Estonian community in Vancouver, home to approximately 1,000 Estonians.

Hansson graduated in economics from the University of British Columbia (UBC), and did his M.A. and Ph.D. (1987) at Harvard University. He returned to British Columbia as an assistant professor at UBC.

Although Hansson’s grandparents and parents had belong to eesti korporatsioonid (fraternities and sororities), they were not Hanssons’s cup of tea, or in Ardo’s own words: “I did not get it.” Likewise, he didn’t join a Canadian fraternity.

Hansson visited Eesti (Estonia) in 1982 and 1985 and found the visits “formative.” He then knew Eesti was a real place and not just a theoretical language and thus attended the West Coast Estonian Days and Kotkajärve Metsaülikool (three times).

By 1988, times had started to change in Eesti, and political kodueestlasted (Estonians living in Estonia) had started to visit Canada. Hansson had met with Mart Laar (who would become Estonian Prime Minister four years later) and Triviimi Velliste of the Estonian Heritage Preservation Society (who would become the Estonian Foreign Minister four years later).

Hansson realized that this was a fork in the road: did he want to be an economics professor in Canada or move to Europe and follow transition economies. Hansson accepted the offer from the research institute in Finland in 1990 and never looked back.

When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, Hansson’s Ph.D. thesis advisor, Jeffrey Sachs, contacted Hansson and asked him if he was interested in working at the WIDER Institute in Finland, an economics research institute that was following transition economies in central and eastern Europe. Hansson realized that this was a fork in the road: did he want to be an economics professor in Canada or move to Europe and follow transition economies. Hansson accepted the offer from the research institute in Finland in 1990 and never looked back.

In 1990, Hansson was travelling with a Soviet visa (Eesti did not become re-independent until August 1991) to Estonia to follow the economic transition that was taking place there. He met with Foreign Minister Lennart Meri who asked Hansson to give economic advice (on a volunteer basis). Hansson also met professors from the Estonian Academy of Sciences and the predecessor university of Tallinn Technical University.

Hansson was making himself known in re-independent Estonia and in March 1992, then Prime Minister Tiit Vähi asked him to be an advisor on monetary reform (again on a volunteer basis), although monetary policy was being formulated at the new central bank, the Bank of Estonia. A Monetary Reform Committee had been set up for Estonia to leave the Soviet “ruble zone” and create a new currency (Estonia previously had the kroon as its currency from 1924 to 1941), with three members: then Prime Minister Tiit Vähi, Governor of the central bank, Siim Kallas, and an independent third member, Rudolf Jalakas. Hansson was the alternative member for the independent member Jalakas. As fate would have it, Jalakas became ill.

As Estonia scrambled to re-launch the Estonian kroon in June 1992, Hansson became a formal member of the Monetary Reform Committee. The kroon was successfully launched. This was the first time a former Soviet republic had left the ruble zone and one of the first times a central and eastern European country re-launched its own currency. When the author put to Hansson that this may be the crowning achievement of his life, Hansson did not disagree.

Hansson stayed on in Estonia, being an economic advisor to prime ministers. As of December 2024, Hansson has been Economic Advisor to six Estonian prime ministers from four different parties (Reform party, Isamaa/Pro Patria, Koonderakond and Mõõdukad/Moderates). He is currently the Economic Advisor to the present Estonian Prime Minister Kristen Michal. Hansson has never belonged to an Estonian political party.

In 1997, Hansson saw that if he stayed on much longer in Estonia, he might not have future opportunities to pursue an international career in economics. So that year, he joined the World Bank office in Warsaw, Poland, and in 2000 was promoted to a full staff position at the World Bank’s Washington, DC headquarters.

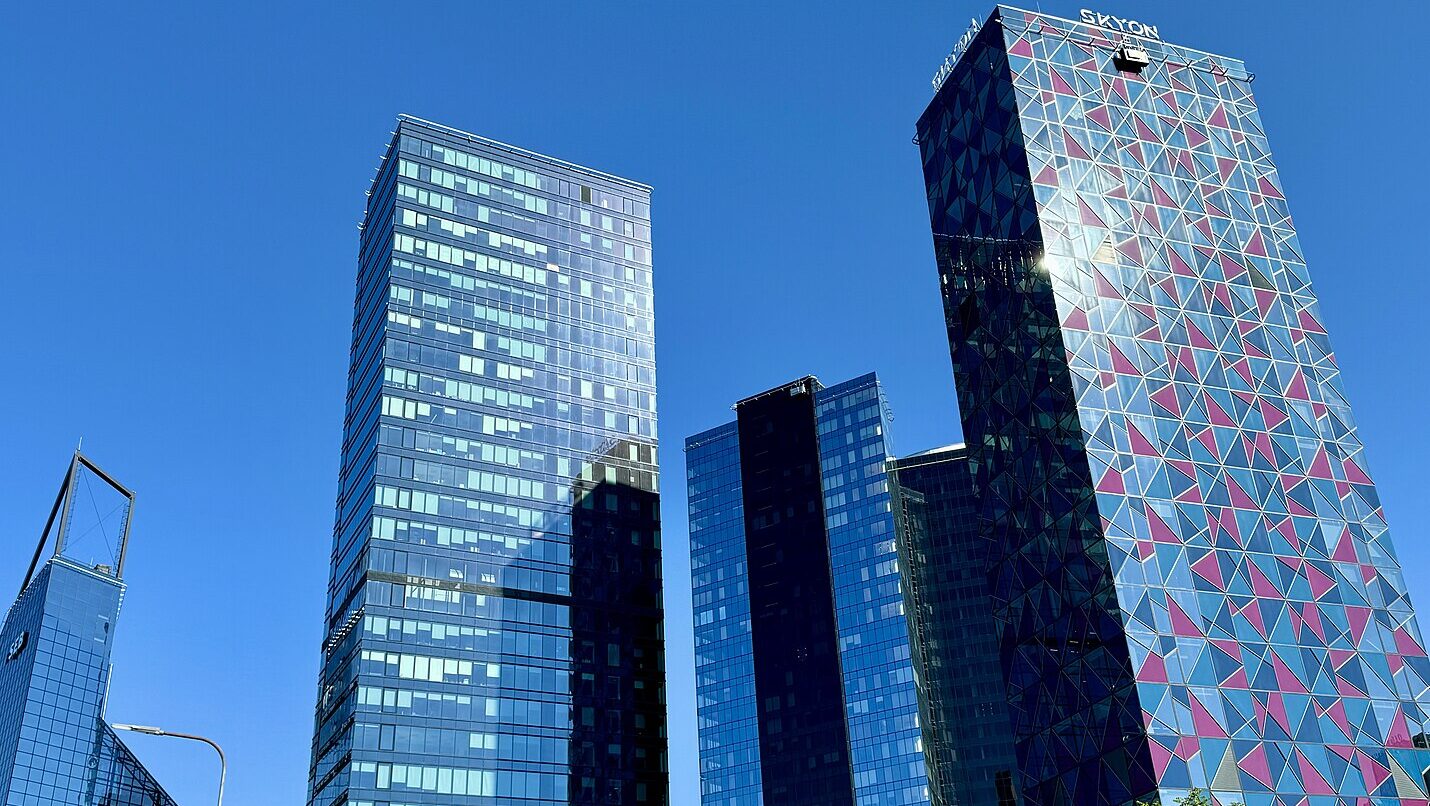

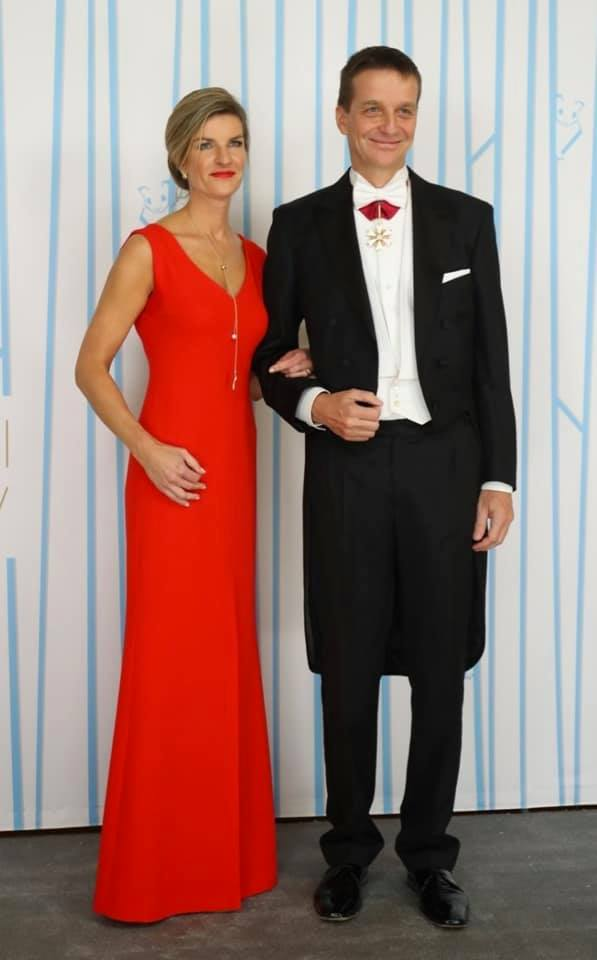

For the next eight years there, he worked as an economist on numerous Balkan countries’ economies. In 2009, he was posted to Beijing, China with his wife Triinu and twin one and a half year old sons, to head up the World Bank’s Economic Unit (number two after the ambassador rank Residential Representative). Living in the US and China, his and his sons’ home language was Estonian. By the time the family left China in 2012, Ardo and Triinu’s sons were beginning to speak accent-free Mandarin Chinese (they were taught Mandarin by their nanny).

In October, 2011, the board of directors of the Bank of Estonia elected Ardo Hansson as the next Governor (or President) of the Bank of Estonia. Hansson took up his new role in June 2012. According to Estonian law, any President of the central bank can only serve one seven year term. As Estonia is a member of the eurozone (i.e. with the euro as its official currency), Hansson, as the Governor of the Estonian Central Bank, held a rotating place on the Governing Council of the ECB, in Frankfurt, Germany, where he attended bi-weekly meetings. Hansson’s term as President finished in June 2019.

Hansson returned to the public sector in April 2021, becoming the Economic Advisor to then-Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas.

When asked by the author how easy it was to raise a family in Estonia (his twin sons are presently in grade eleven), Hansson replied that in general it was a very good environment in which to raise children. But one needed to get the timing right when entering the Estonian school system. Ardo and Triinu were fortunate that when they returned to Estonia, their sons were five years old. Estonian children begin attending school at the age of seven, so their sons could begin school in grade one. Hansson emphasized the importance of entering the Estonian school system right at the beginning (ideally kindergarten or grade one). As Estonian schools are rigorous and demanding from early on, Hansson doubted whether children could “catch up” if they entered the Estonian school system at a much later age. Hansson is very happy with the quality of the education his children are receiving at the Vanalinna Hariduskolleegium.

It might take some time to find an employer in Estonia looking for that skill set. One would need to be prepared to perhaps do something else for a while and to branch out before finding a job that’s suited to one’s skill set.

The author also asked Hansson what advice Hansson would give people who are thinking of moving to Estonia. Hansson made two comments. He said that it was important to get one’s expectations right. Living in Estonia is no longer a “hardship posting” as diplomats would have once called it. Also, younger generations all speak English. But it is a smaller, closed society where many people have grown up together and attended the same schools and universities. It’s harder to break into than large countries with significant amounts of immigration.

The second piece of advice was that, given Estonia’s smaller size, there are less opportunities for anybody with a very specific skill set. It might take some time to find an employer in Estonia looking for that skill set. One would need to be prepared to perhaps do something else for a while and to branch out before finding a job that’s suited to one’s skill set. One might need a bit of luck to get off on the right foot and not be disillusioned if things do not click into place during the first months after arriving in Estonia. But there’s a great deal of inspiration one can take from the adaptability of Hansson and his family.

Eesti Elu considers itself fortunate to obtain an interview with Hansson, as the Estonian media are always requesting interviews from him, asking him what advice he is giving the Prime Minister. Hansson noted that if he has something to say, he will tell the Prime Minister directly and not have them read about it in a newspaper.