Standing outside at the intersection of Hollis Street and George Street, both of these buildings stand firmly in stone, the former with a more plain appearance and the latter bearing ornate column capitals. It's not a purpose-built facility, and unfortunately, it doesn't go unnoticed. With questions surrounding making the most of existing buildings, financing, and the possibilities of new construction, there are similarities between the development of the International Estonian Centre and the new Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

AGNS was in need of more office space and storage for its growing collection of art when the Provincial Building became part of the gallery's expansion project in 1998. When the gallery's 100th anniversary came around in 2008, that need was still there, and the director then, Ray Cronin, put forward his commitment to remake the gallery entirely. Current director Nancy Noble, appointed in 2016, is continuing this commitment. In November 2020, after a half-year international design competition and the Design Competition Exhibition that started in September 2020, one of three designs was chosen for the new Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. With public conversation encouraged and designs considered by a jury of professionals, the choice became KPMB Architects, together with Omar Gandhi, Jordan Bennett Studio, Elder Lorraine Whitman (Native Women's Association of Canada), Public Work, and Transsolar.

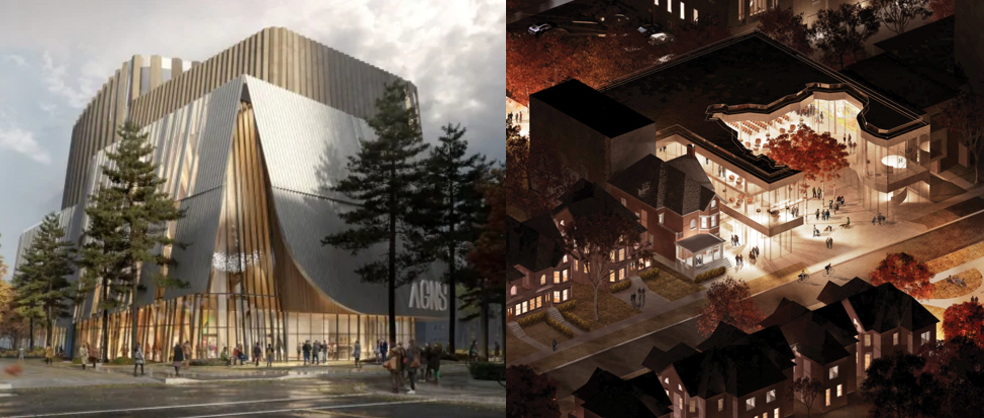

Among the most noticeable differences in this design from the existing AGNS facility are the gallery's location and the shapes that illustrate the knowledge of the Mi'kmaq people in Nova Scotia. Renderings of the new gallery show the building moved down to the corner of Salter Street and Lower Water Street. It extends out all the way out to Halifax Harbour, where there is currently a large parking lot.

Wherever walls meet, curves are used instead of right angles, which are believed to trap energy. This curvature emulates the organic shapes of nature.

Where the front of the gallery faces the street, the defined shape of a peaked cap like those traditionally worn by Mi'kmaq women is visible. Passing under this shape, visitors enter into the Mawiomi Odeum. Mawiomi means “a gathering.” The space rises up high with light let in between the sloped timber columns. Wherever walls meet, curves are used instead of right angles, which are believed to trap energy. This curvature emulates the organic shapes of nature.

The exterior's metal, terra cotta, and timber will ideally be sourced locally, built with a vertical orientation that's meant to resemble Mi'kmaq basket weaving. The overall building is lower in height than surrounding buildings and ripples out to the water like the body of katew (“eel”), an animal that has been a vital part of traditional Mi'kmaq meals and ceremonies, and reflects a relationship of respect for all living organisms. Around this shape, spaces outdoors are designed to be inviting for gatherings and events.

The total cost of the new gallery is 130 million Canadian dollars, with 70 million coming from the Nova Scotia provincial government, 30 million from the federal government, and 30 million from AGNS fundraising. As voiced by Jennifer Angel, CEO of Develop Nova Scotia, once the gallery is completed in 2025, it can bring the local community closer together. Considering Halifax's substantial tourism industry from visiting cruise ships, it will give these cruises another solid reason to stop in the city.

The cast foam aluminum panels surrounding the tops of floors point to the practice of õnnevalamine (literally “luck pouring”), where drips of cast metal are used to predict the future.

Symbols are also used in the design for the International Estonian Centre. For instance, the shape of the centre's courtyard follows the contours of mainland Estonia's borders. Birch trees in the courtyard remind visitors of the glowing white forests of Estonia, while local vegetation on the roof terrace also ties the outdoor spaces to Canada. The cast foam aluminum panels surrounding the tops of floors point to the practice of õnnevalamine (literally “luck pouring”), where drips of cast metal are used to predict the future.

Wood floors elicit the aesthetic of modern Nordic design, where neutral surfaces become a canvas for splashes of colour, as would come through in events and exhibits. There is room for music to resonate and fill the community areas. Space and minimalism are understated symbols of heritage that reflect the wide open Estonian landscape.

Looking ahead years from now, in either of these completed buildings, there will be time and space to examine subtle details that remind us of where we came from.