Some of us even set up the ability to switch keyboards depending on what languages we’re writing in most. Depending on who one is writing to, there’s something fun about hovering over the taskbar and switching the keyboard—a test of how much you’ve memorized a keyboard different than the one you can actually see in front of you—or (once upon a time) knowing the right hotkeys to produce the letters Õ, Ä, Ö, Ü, Ó, Ô, Ã, À, or È.

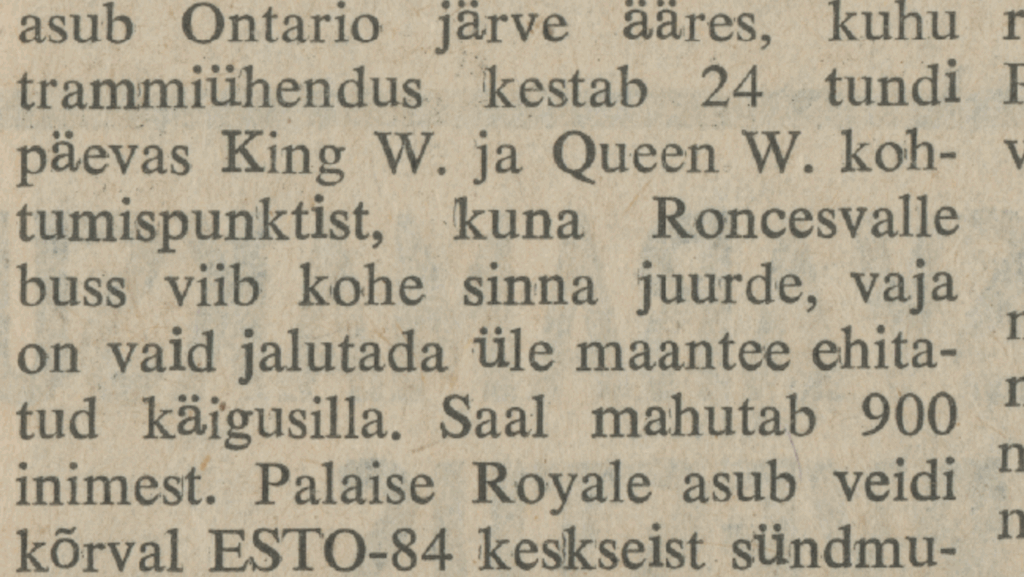

But this still pales in comparison to the physical challenge of what printing professionals have had to deal with throughout the history of printed newspapers, books, and so on. What prompted this thought? Looking closely at a scanned copy of Vaba Eestlane newspaper from Thursday June 14th, 1984. Every time the letter Ä, Ü, or Õ appears, the letter is slightly higher than the others around it in a word. It’s almost as if they were printed after the fact on newsprint that was missing those letters—where words would have looked like “k igusilla” (käigusilla), “j rve res” (järve ääres), and “k rval” (kõrval). It wouldn’t appear that the letters without the diacritics were printed and diacritics added after. It’s possible that that might have resulted in messy printing.

For the sake of a more thorough investigation, let’s look at a copy of Vaba Eestlane from March 1st, 1977 and from October 20th, 1965 (prior to ORTO Estonian Publishing House Ltd. closing in 1973). In the 1977 paper, letters with dots above show up without any inconsistencies, although sometimes the diacritics blend a bit with the tops of capital letters. On occasion, the letter Õ appears at slightly different levels from the rest of the words. However, in the 1965 paper, few irregular letters are found. This is looking primarily at serif typeface text as opposed to headlines and ads in sans serif typefaces.

Did Estonians of the diaspora… have a more difficult time acquiring or maintaining printing machinery and parts than publications that didn't use any (or not as many) letters that existed outside of the English alphabet?

Observations like these lead us to wonder what the technological realities and limitations were at the time. Did Estonians of the diaspora in English-speaking countries, with their own distinct language and alphabet, have a more difficult time acquiring or maintaining printing machinery and parts than publications that didn't use any (or not as many) letters that existed outside of the English alphabet?

Swedish, which has its fair share of diacritics such as Å, Ö, and Ä, was printed without any apparent difficulties way back in April 1890, looking at a copy of Arbetaren, a historic Swedish-American newspaper. Der Deutsche Canadier, a German newspaper published in Kitchener, Ontario in the mid 1800s, is kitted out with a Fraktur typeface (an interesting side note: while Fraktur is seen as a distinctly Germanic typeface, beloved by the likes of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, it’s said that Adolf Hitler disliked it and banned its use in 1941, which may have maximized the impact of propaganda in the countries that Germany occupied). The size and financial resources of diaspora communities would have impacted what was possible in terms of printing.

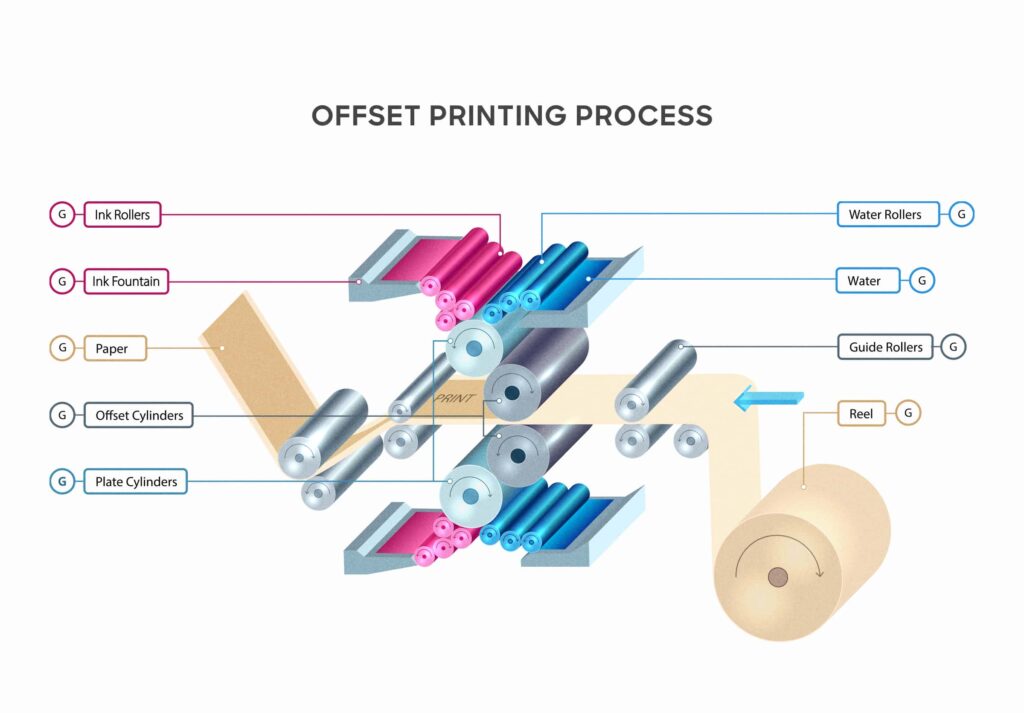

Regardless of the necessary extra considerations of those printing in the Estonian language, printing newspapers has been a challenge throughout history. The first printing press, of course, was created by Johann Gutenberg. This “movable type machine” meant that metal letter blocks could be arranged (in reverse), rolled with ink, and have paper pressed and rolled onto them. As the Utica Observer-Dispatch describes, 19th century inventions such as “A motorized, turning cylinder embossed with raised lettering” sped up the process substantially. By the 1960s, offset printing became the dominant form of printing newspapers, wherein “the images on metal plates are transferred (offset) to rubber blankets or rollers and then to the print media,” as TechTarget defines it. To this day, this method is popular when printing takes place on a large scale, while digital printing works best on a small scale because making plates for offset printing is expensive.

Even so, printing has become more and more expensive, connected to things like rising fuel costs, higher raw material prices, labour shortages, and the closure of paper mills during the Pandemic. All the more reason to financially support your local newspapers, authors, illustrators, photographers—anyone involved in the business of publishing media that we enjoy consuming. And frankly, even without print media, the creators of this material we consume need systemic support. This media may not always be tangible, like a meal or drink at a restaurant, but our lives are enriched by it.

All this is to say that each letter on a printed page, including this page if you’re reading in print, is a miracle. A miracle made possible by the sweat on someone’s brow, by inventors, and by people with ideas. It’s a wonderful thing.