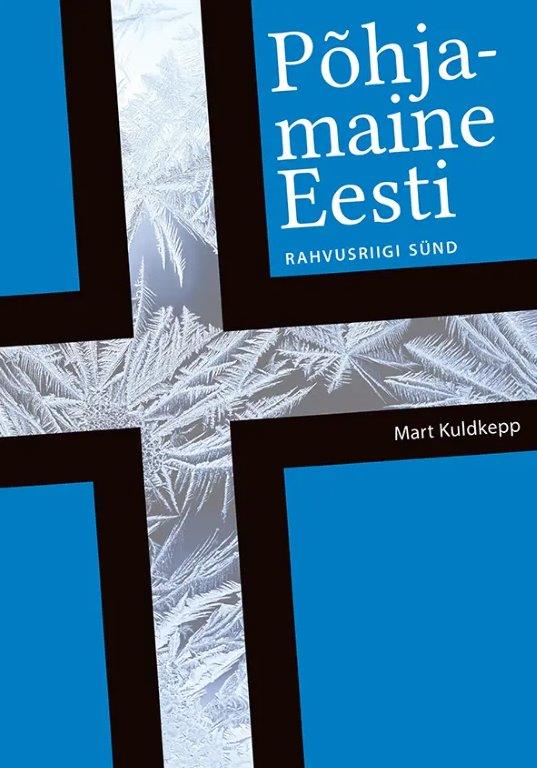

A week and a half before our flag-raisings, concerts, speeches and medal presentations a timely interview with Mart Kuldkepp was posted online on February 15th at the Novaator (ERR) website. Kuldkepp is Professor of Estonian and Nordic history at University College London. He defended his doctoral thesis, “Estonia Gravitates Towards Sweden: Nordic Identity and Activist Regionalism in World War I” at the University of Tartu in 2014. On January 31st publishing house Varrak released his book on the topic Põhjamaine Eesti. Rahvusriigi sünd (Nordic Estonia. The Birth of a Nation). Kuldkepp was interviewed by Andres Reimann.

Kuldkepp’s research over 15 years originally began with the 1920’s and 1930’s for his Bachelor’s thesis. But over time he found himself searching earlier influences, returning to the beginning of the 20th century and the book’s theme of a Nordic consciousness, the expression of it and how this was politically expressed was formed.

In a nutshell Kuldkepp argues that over the 700 year-long period of serfdom, servitude, pärisorjus (perhaps best translated as indentured slavery) before the founding of Estonia our nationalists considered the Swedes to have been the best, most suited rulers of our land and people. Certainly better than the Baltic Germans or Tsarist Russia. Hence the expression still known and used today found in the title of this article.

The historian argues that before 1918 an independent Estonia was not seen as a realistic goal. There existed a preference for a larger, more secure confederation.

A hope arose during WW I that with the collapse of two empires, Imperial Russia and Germany, that maybe a return to Swedish rule would be the best option for Estonians. This idea was most fervently expressed by Aleksander Kesküla, a revolutionary in 1905 and then an émigré agitator. He pushed for not only a Swedish ruler but for a co-operative confederation framework, seeing Estonia allied with Germany and quite curiously France. None other than Eduard Laaman, without a doubt our most respected historian of Estonia’s War of Independence, wrote in 1918 that Kesküla’s influence in Estonia was about as great as his sway in the Sandwich Islands. True, but Kesküla, while an oddity merits more than a footnote of the history of those turbulent days. Kuldkepp notes that Estonian nationalism of the time was quite colourful and varied (kirju).

The historian argues that before 1918 an independent Estonia was not seen as a realistic goal. There existed a preference for a larger, more secure confederation. Perhaps not surprisingly, considering the tenor of the 19th century, it can be claimed that earlier Estonian nationalism had elements of colonialism. Of establishing footholds on the other side of Lake Peipsi and Narva well into Ingria, Ingerimaa, the historical region in what is now northwestern European Russia.

The question then remains: are Estonians Nordic, Scandinavian? Northern European, sure. But this is a question of personal rather than political definition.

Kuldkepp asserts that the Declaration of Independence on February 24th was, while certainly not coercion or a dictate somewhat forced (sundolukorras), without preparation on an intellectual, practical level. For him the teleological narrative, which presents independence as the only possible result of nationalist expression does not hold water.

The question then remains: are Estonians Nordic, Scandinavian? Northern European, sure. But this is a question of personal rather than political definition. And according to the 20th century historical experience Nordic countries followed a different path from Estonia. There was certainly a need to present as unique, a people born nor from historical error but as a stand-alone region with both a distinct separate history from surrounding areas but such a future as well as a named, defined country.

As a curious aside, Laul Põhjamaast, (Song of a Nordic land) is considered to be a patriotic song, a staple of our Song Festivals. In fact, conductor Tiia-Ester Loitme, conducting the massed choirs in 2019, exhorted the singers to remember before giving voice – this is a holy song, a hymn, a prayer. Because, as the lyrics by Enn Vetemaa emphasize, this Nordic land is our birth-land, a rough land and a tough land. A land of waves and shores, battlefields and carnage but also of beauty, so dear to us on our far away trails, ever in our soul. It ends – never shall I leave the homeland.

This song, composed by Ülo Vinter (the centenary of his birth was marked on January 3rd) was written for the 1969 musical based on Pippi Longstocking (Pikksukk), Astrid Lindgren’s famous superhumanly strong Swedish tomboy, able to lift her horse one-handed. It was so popular that there was a faction encouraging the adoption of this gentle, lyrical but perhaps too tender song as the national anthem after the regaining of independence. Fortunately this idea was not taken seriously. Still. There is a faction of those longing for Swedish times.

The arguments whether we belong to the Baltics or to the Northern lands are age-old. We have much more in common culturally and linguistically with the Finns, separated from us by 80 kilometres of the cold briny Baltic Sea than we do with our southern land-border neighbours, the Latvians.

Kuldkepp’s book is awaited on these shores for in-depth study. For those with a command of Estonian the Novaator interview is highly recommended as intriguing and educating reading.