Directed by Evald Mägi and written by Eerik Heine, Legendi loojad might be considered part of the early Estonian diaspora film canon, along with films like Seitse vihta. Released in 1963, the film was a passion project, made by Estonians in Canada, telling the stories of the Forest Brothers in their resistance against Soviet occupation. For Vancouver resident Olev Jaaguste, who acted in the film as a boy and whose father Helmut Jaaguste played Väino, a Forest Brother, Legendi loojad goes beyond being a piece of Estonian cultural history. It’s a family treasure and a vital link to a nearly-lost legacy.

Olev’s father Helmut was committed to Estonian cultural preservation and the struggle for independence, which found its way into the film and many other community activities. Olev himself, at twelve-years-old, appeared in a small role dressed as a Soviet soldier holding a prop submachine gun. His memories of the production are limited, but he does recall snowy days filming, potentially at Seedrioru Estonian Children’s Summer Camp, where he “put on the Russian gear… and just stood around, being pointed to move over here and move over there.”

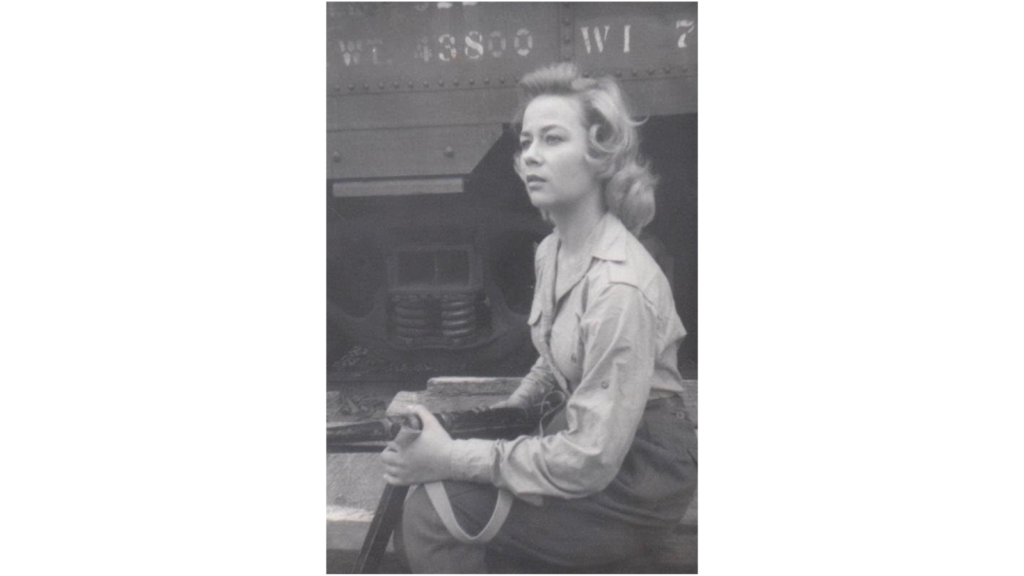

The film itself is a dramatization of the Forest Brothers’ lives, based on the personal experiences of writer Eerik Heine, a former Forest Brother. Set during the post-World War II years, the story follows Captain Lembit Mõtus (Arvo Vabamäe) and his group of partisans as they resist Soviet forces. Themes of sacrifice, resilience, and the yearning for freedom pervade the narrative. The Forest Brothers’ defiance against a powerful enemy resonated with the Estonian diaspora, who watched their homeland suffer under the Soviet occupation.

Upon its release, Legendi loojad was shown to a relatively small number of people, including approximately seventy viewers at the Estonian House on Broadview Avenue in Toronto. In January 2014, the film was screened by VEMU at Tartu College. But since its first release, the film has largely been forgotten. And for Olev Jaaguste, its historical and emotional significance has been overshadowed by personal tragedy.

Bringing Legendi loojad back to the attention of Estonians and improving its technical quality became a quest to reclaim part of his family’s heritage.

The Jaaguste family faced a series of misfortunes. Helmut passed away at age fifty-nine. The family home, along with Helmut’s artwork, scouting memorabilia, and Olev’s childhood skiing trophies, was destroyed in a fire. Later, a family photo album painstakingly crafted in leather by Helmut was stolen. These losses left Olev with few tangible connections to his past. Therefore, bringing Legendi loojad back to the attention of Estonians and improving its technical quality became a quest to reclaim part of his family’s heritage.

Over the years, the film’s story has been in danger of being lost to history. Determined to preserve it, Olev began searching for a copy. Through contacts in the Estonian community and institutions like the National Archives of Estonia, he obtained a version with English subtitles. However, the film’s audio and visual quality were poor, making it difficult to appreciate.

Undeterred, Olev sought modern solutions. Investing his own personal funds, he enlisted the help of John Romein, a family historian and film technology expert in Port Coquitlam, BC—who is familiar with editing and enhancing archival material—to use artificial intelligence software to restore the film. The software has worked in improving facial features and sharpening the overall resolution, transforming the grainy footage into something closer to its original form. Olev is optimistic that the enhanced film can be shared with his family and the broader Estonian community.

However, the journey to make the film more widely accessible faces legal hurdles. The rights to Legendi loojad were originally held by Richard Jurss, a key figure in the film’s production. Jurss has since passed away, and so Olev is in the process of obtaining permission from the current rights owner.

Furthermore, Olev hopes that community organizations might support his efforts. His ultimate goal is to transfer the rights to an organization that can distribute the film on his behalf. He envisions screenings that bring together members of the Estonian diaspora, educating future generations about Estonia’s fight for freedom and the resilience of its people, both in terms of the Forest Brothers themselves and the Estonian-Canadians who made the film.

As Olev awaits the final restored version of the film, he looks forward to sharing the final product, adding “to be able to see my dad again in the movie will be spectacular. It’s such an important record, personally, but also for the wider Estonian community.”

If you know anyone involved in the creation of the film or would simply like to purchase your own copy of the film once permission has been obtained, contact Olev at jguste@telus.net .