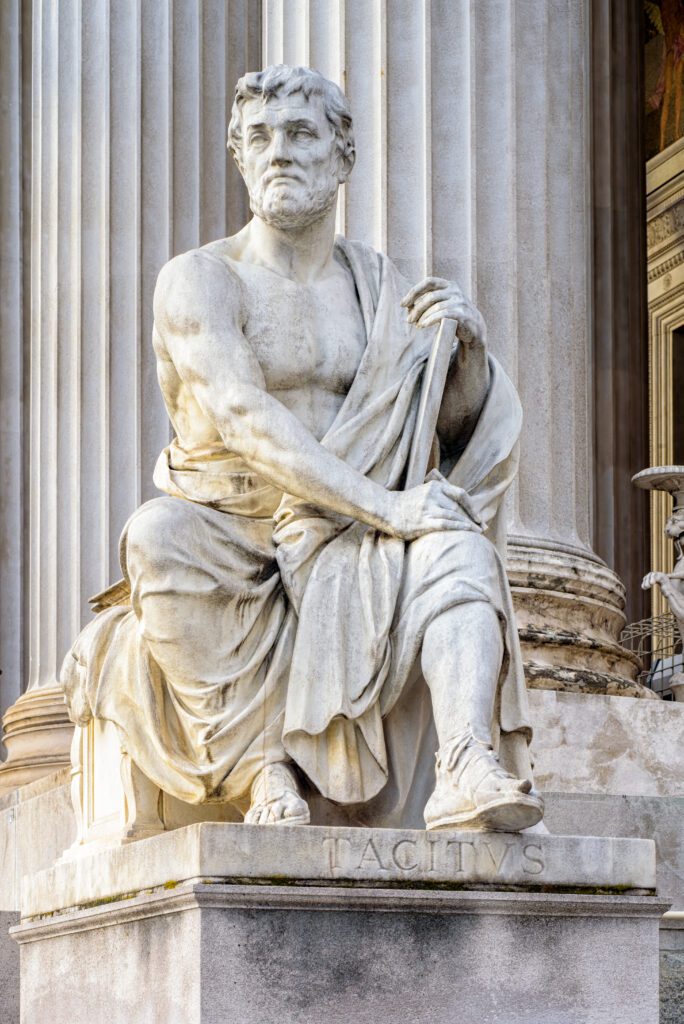

While some scholars argue that Tacitus was actually referring to the descendants of modern-day Latvians and Lithuanians, there are geographic indications that he was at least talking about an area that could include what is now Estonia.

He describes how, “Beyond the Suiones [the tribe living in present-day central Sweden] is another sea, sluggish and almost stagnant…the last light of the setting sun continues so vivid till its rising, as to obscure the stars…”

Tacitus may be referring here to the northern reaches of the Baltic Sea, which has been known to freeze over in particularly cold winters (the last instance being 1987, when 96% of the Baltic Sea froze). He is also most certainly commenting on the long days around the time of the summer solstice.

From there, Tacitus continues, “On the right shore of the Suevic sea dwell the tribes of the Aestii, whose dress and customs are the same with those of the Suevi, but their language more resembles the British. They worship the mother of the gods; and as the symbol of their superstition, they carry about them the figures of wild boars.”

While Tacitus' linguistic comparison to the language of the Britons doesn't hold up in the present day, the name Aestii was again mentioned by Jordanes, a government official from the Eastern Roman Empire, when he briefly wrote of “the Aesti, who dwell on the farthest shore of the German Ocean…” This was in his 6th century CE text The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, 221 years after the Roman Empire was split into east and west by Constantine I. To be clear, Aestii was a name given from outside to the inhabitants of this region.

Tacitus' description of geography, local beliefs, and customs aligns to a degree with what is now known about the Baltic region and its history. Speaking about how the Aestii survived, Tacitus wrote, “Their weapons are chiefly clubs, iron being little used among them. They cultivate corn and other fruits of the earth with more industry than German indolence commonly exerts.” This particular translation of “corn” doesn't add up of course, as Europeans weren't aware of corn until Christopher Columbus brought it back from the Caribbean in 1493.

However, as Professor of Archaeology Valter Lang writes in his 2007 book The Bronze and Early Iron Ages in Estonia, “The earliest evidence of cereal cultivation in the eastern Estonian pollen diagrams dates to 4000 BC…” In addition, Professor Lang notes “The first landnam [a transition from foraging to agriculture] also came to an end in central and southern Estonia by the beginning of the Roman Iron Age.” Indeed, Estonians would have been engaging in agriculture in the time of the Roman Empire.

Just after this, Tacitus writes about the act of collecting amber. He writes, “They even explore the sea; and are the only people who gather amber, which by them is called Glese, and is collected among the shallows and upon the shore.” As discussed by The J. Paul Getty Museum, Baltic amber from approximately 38 to 28 million years ago has been primarily excavated“from today’s Lithuania, Latvia, Russia (Kaliningrad), Poland, southern Sweden, northern Germany, and Denmark.” This, in turn, indicates that he was at least partially writing about Latvia and Lithuania.

Tacitus is very condescending in his descriptions of this region, adding “With the usual indifference of barbarians, they have not inquired or ascertained from what natural object or by what means [amber] is produced. It long lay disregarded amidst other things thrown up by the sea, till our luxury gave it a name.”

Examining these descriptions, can we truly look at Germania as a historical record of Estonia in ancient times? The closest that the Roman Empire reached towards Estonia, even at its greatest extent in 117 CE, was Dacia, or present-day Romania. And from a historiographical perspective, for decades it has been debated among academics whether Tacitus ever spent time in the regions north of the Roman Empire. It's more likely that Tacitus' book was based on interviews with military personnel, traders, or other extraordinarily adventurous people. Likewise, texts written by historians from before could have supplied information.

In a contemporary sense, the book has raised concerns, by Stanford University Associate Professor Chrisopher Krebs among others, for how his writing influenced the Nazis' racist agenda and plans. Early on in Germania, Tacitus states his belief that Germanic peoples are “a race, pure, unmixed, and stamped with a distinct character… eyes stern and blue; ruddy hair; large bodies, powerful in sudden exertions, but impatient of toil and labor, least of all capable of sustaining thirst and heat. Cold and hunger they are accustomed by their climate and soil to endure.”

When one steps back from excerpts of Germania and examines the text as a whole, a few things are noticeable about his writing. Namely, Tacitus writes in a very generalized way. Readers are given relatively small pieces of detail before the next point is presented. There is also an underlying contempt and sense of Roman superiority in his tone.

So what can we take away from all of this historical description? While it is intriguing to consider how Romans might have viewed Estonia and the Baltic region on the whole, we must assemble a larger collection of sources to more deeply understand this time and place.