In conversation with poet and artist (and Eesti Elu reader) Jaak Viirland, I was made aware of an artist whose creative impact we might be able to engage with as Estonians in Canada. His name is Ülo Kelmser.

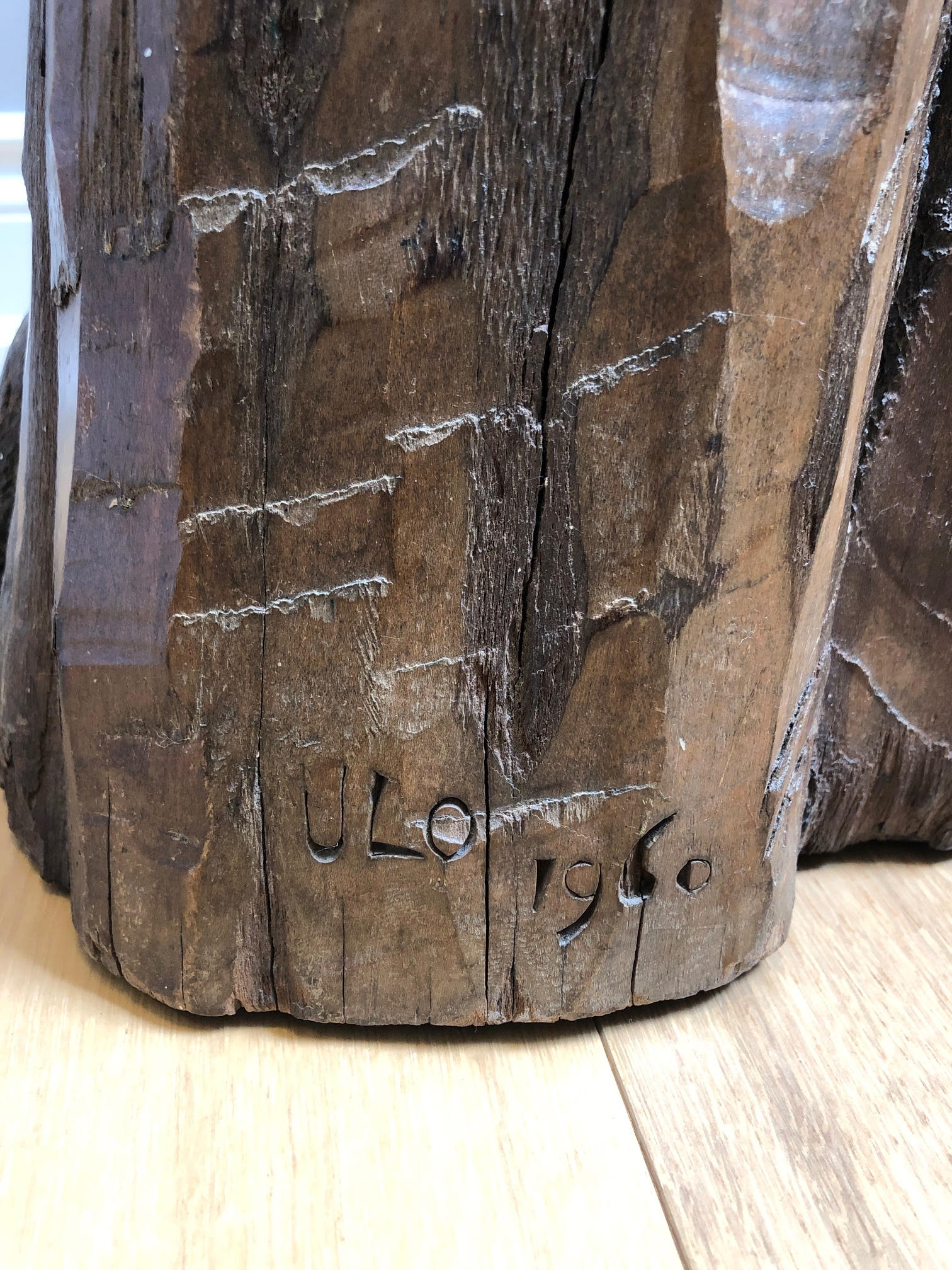

Kelmser was a wood carver (a “wood butcher” as he described himself), who made carvings that can be found around Ontario. Typically they were centred around religious themes, church decorations being the bread and butter of his craft. Although, according to Viirland, he created in other styles as well. This includes Polynesian-style carvings that were featured in a “Polynesian lounge” in Burlington and a Chinese restaurant in Hamilton. He also spent time in First Nations communities in Hagersville and Caledonia, which was where he made pieces that resembled monumental poles from the Pacific northwest.

What’s most enjoyable about his carvings, of what we can still find, is their complexity and expression. Speaking of one of Kelmser’s carved poles, Viirland states that the “detail of those faces on that totem pole is unbelievable.” Another piece, what Kelmser called “the ponytail,” is a carved head on top of a twisted root. Viirland points to the angle of the wood and compares it to “an angel looking down…” At other points, though, he was more loose in his technique. One carving is of a long, inquisitive face, looking up to the heavens with wide eyes and a big nose.

Photo gallery

One finds much praise for Kelmser’s art from the written records of his peers. For example, in Frontiers and Sanctuaries: A Woman's Life in Holland and Canada, the titular woman, Madzy Brender à Brandis-van Vollenhoven, is quoted, reacting to Ülo and his carvings: “Ulo was a strange person but also very friendly… tall, strong… a very good artist… I had seen several of his Christs on the cross and Mary figures and other religious statues and they filled me with awe as centuries-old sculptures do…”

“To [Madzy] this seemed like sacrilege but Ülo just laughed, took up one of his superbly sharp chisels and shaved a thin layer of wood from the sculpture thus destroying his diagram…”

(Gerard Brender à Brandis)

In 1963, Brender à Brandis-van Vollenhoven and her son—the Stratford, Ontario-based wood engraver Gerard Brender à Brandis—were drawing students of Norma Waters, an artist and Ülo Kelmser's partner. In their studio, Gerard recalls that Kelmser was “working on a life-sized wooden sculpture of the Virgin.” When asked about his work, Kelmser “illustrated his explanation by taking up a pencil and making a diagram on the unfinished sculpture. To [Madzy] this seemed like sacrilege but Ülo just laughed, took up one of his superbly sharp chisels and shaved a thin layer of wood from the sculpture thus destroying his diagram…”

Gerard emphasized, “I do not think it an exaggeration to suggest that this time shared with Ülo in his studio and seeing his veneration for wood and his superb work with the sharpest of cutting tools might have influenced my decision to become a wood engraver…” His impact is felt in at least one other artist. This is the greatest possible result of an artist’s work.

Gerard believes that the sculpture of the Virgin Mary was “commissioned for the Church of Our Lady on Plains Road in Burlington.” This would appear to be Holy Rosary Church, upon which you can still see such a sculpture below the gable. Mary’s left arm is raised to her heart and her right arm reaches down, framed by a long flowing cloak.

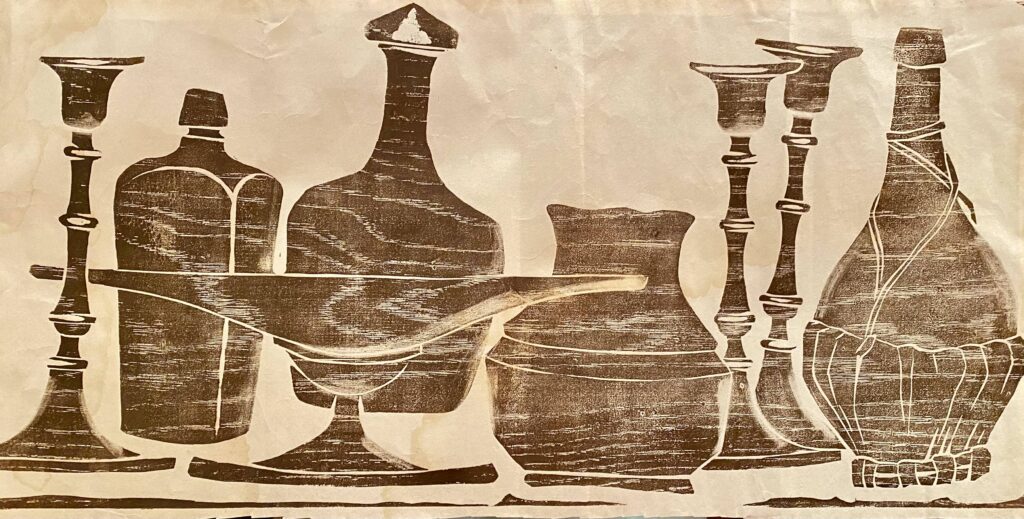

It also turns out that Kelmser made many woodcut prints. Being good friends with him from 1958 onward, Jaak Viirland would help Kelmser make prints on rice paper in the basement studio of Alan Gallery (then at 484 Main Street East, Hamilton, owned by Alan Oddy). These prints include images of the Burlington Skyway and subject matter like fish and liquor bottles.

Still, the whereabouts of much of Kelmser’s art is a mystery. Some pieces went missing, including four that Viirland brought to a gallery in Coconut Grove, Florida. But knowing more about Kelmser may pinpoint the whereabouts of other pieces.

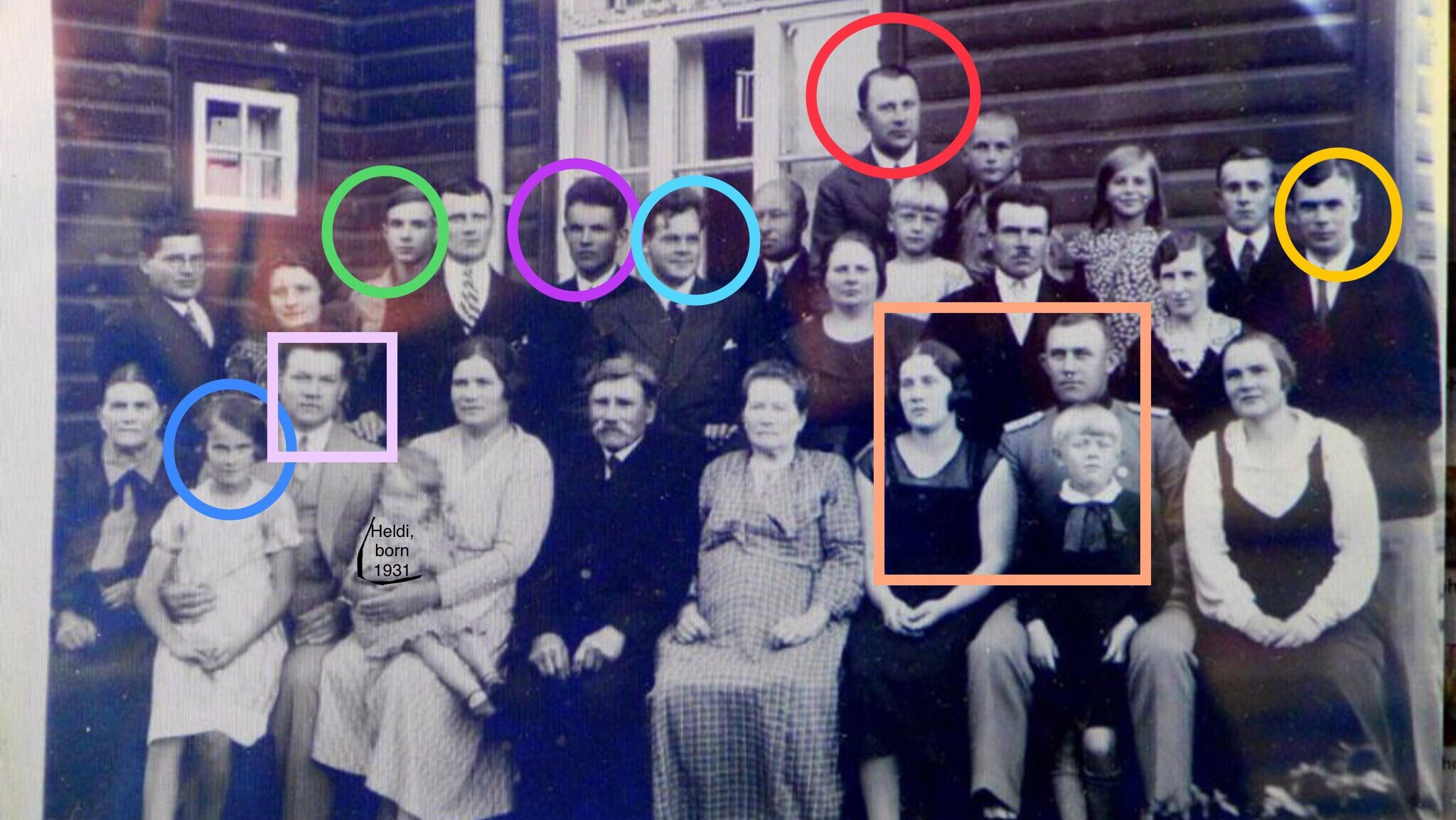

Kelmser was born on July 30th, 1925 in Rapla, Estonia. According to the biographical lexicon of soomepoisid published by Estonian World Review, Kelmser volunteered for the Finnish Navy in December 1943, at the age of 18. By August of 1944, he went to Sweden, and then to Canada in 1947.

He carved with chisels, but his hammer was some kind of bowling ball attached to a handle.

Based on a small notice in Stockholms-Tidningen Eestlastele from August 1953, Ülo was already working as a wood carver in a Dundas, Ontario craft centre. It would seem that he was self taught, especially considering his tools weren’t totally orthodox. He carved with chisels, but his hammer was some kind of bowling ball attached to a handle.

Outside of art, he was involved in Estonian community activities. In a June 1957 issue of Vaba Eestlane newspaper, he is listed among several others as a dancer in the Hamiltoni Eesti Selsti Rahvatantsurühm group. There’s even a photo from this era of Kelmser in his rahvariided.

However, his main circle of friends consisted of Viirland, Seppo Viljasoo, and the painter Helen DeSilaghi Bethlen Sirag (AKA “Bobbi”). There was an artistic connection here. Just as Kelmser would say “the wood talks to me”, Bobbi had caused quite a stir in the area for her painted depictions of astral projections and “cosmic walks” that she would sometimes experience.

What brought an early end to Kelmser’s wood carving were his mental health troubles. One winter, Kelmser attempted to kill himself. There are inconsistencies in sources that tell us when this happened. But we know that in the aftermath of this suicide attempt, he suffered from a stroke and became paralyzed on one side of his body.

“He did the entire interior carvings for a church out west and one in Bracebridge. He carved a beautiful picture of the Last Supper amongst other works.”

(The Georgetown Herald, October 26th 1972)

After this, he was moved into Halton Centennial Manor, a long-term care facility, where he worked on watercolours and rug hooking. An article from The Georgetown Herald on October 1972 describes Kelmser’s time there, saying it was “very sad to look upon such a gifted person knowing that the talent he had is no longer available to enjoy.”

Still, the article mentions his past, that “He did the entire interior carvings for a church out west and one in Bracebridge. He carved a beautiful picture of the Last Supper amongst other works.”

This is an open call to the Estonian community of Canada. If anyone knew Ülo Kelmser, or knows the location of a sculpture of his, maybe something can be done to hold onto that art and those memories for future generations.