Her use of digital technologies as mediums for these works places her within the realm of cyberfeminism, making her one of the first Estonian artists to do so.

Although its roots extend further back, cyberfeminism emerged mainly in response to the advent and proliferation of the internet and digital technologies. Early cyberfeminists sought refuge from traditional norms, values, and identities within these new virtual spaces, perceiving them as powerful catalysts for female liberation and expression — an idea first articulated by Donna Haraway's seminal 1985 essay A Cyborg Manifesto.

…artists [painted] early “network culture” as an inundation of macho-manhood: many video games presented overtly sexualized characters, “hacking” was a man's game, and chat rooms were home to harassment — this time with the added feature of anonymity and perceived impunity.

However, these thinkers soon realized that, far from being harbingers of liberation, the technological architecture of the online realm replicated the very oppressions they meant to escape. Izabella Scott's “Brief History of Cyberfeminism” in Artsy draws on various artists who paint early “network culture” as an inundation of macho-manhood: many video games presented overtly sexualized characters, “hacking” was a man's game, and chat rooms were home to harassment — this time with the added feature of anonymity and perceived impunity. In response, artists, scholars, and various theorists sought to reclaim digital technologies as vehicles of feminist self-expression, resistance, and social change.

It was around this time that Estonia was undergoing a number of societal transformations. Shortly after regaining its independence from the Soviet Union, Estonia embarked on a national project to embrace digitization. Known as Tiger Leap, the project marked the beginning of the country's investment in information computer technologies and network infrastructure, to distinguish itself from its occupied past.

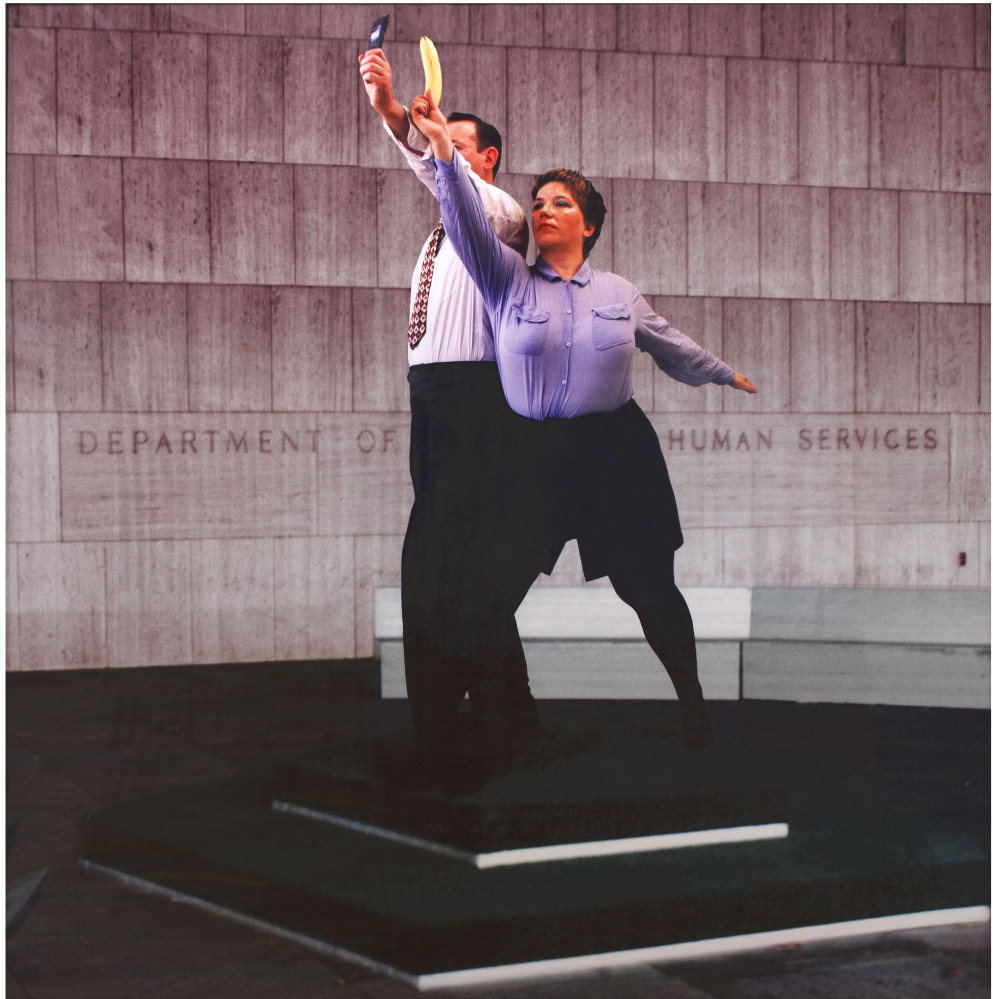

Tralla's work reflected these changes and their impact on Estonian women. Through humour, irony, and visual grotesque, Tralla uses digital technologies to critique gender norms, particularly in the context of a newly independent Estonia. In fact, she was one of the first in the country to do so with the opening of her exhibition Est.Fem in 1995, which featured her video installation So We Gave Birth to Estonian Feminism alongside the work of her co-curators and other artists — a performance which earned her the nickname “disgusting woman” by the Estonian press for her vulgar critiques of the feminist movement in Estonia at the time. “For part of my life, I tried to be quite someone else, act in accordance to what society regards as normal, but nothing came of it,” she said in an interview with Estonian Art. “My inner self revolted against the prison, thirsting for freedom. To a certain extent, I have liberated myself since I no longer am afraid to say what I think and feel.”

Tralla's use of irony as a tool of liberation makes her videos highly personable. Her 2004 autobiographical video “The Heroine of Post-Socialist Labour,” for example, traces the evolution of beauty standards and norms for women from pre- to post-independence. Clips of Tralla struggling to follow makeup tutorials and Jane Fonda-esque workout videos are juxtaposed with footage of Soviet women performing manual labour, conveying the idea that, despite structural changes in Estonia (and Eastern Europe more broadly), which opened up an entirely new realm of possibilities economically, socially, and politically, the expectation that women should mould themselves to society's norms, traditions, and values remains the same.

Her description of the performance on Vimeo says, “During the Soviet time, women were celebrated as working heroines: milkmaids, tractor drivers, factory workers, etc. Feminine aspects of womanhood and everyday life were overlooked, and some even tabooed. Therefore, it is not surprising that women in the new independent and capitalist societies of Eastern Europe are obsessed with the notion of femininity and ‘feminine beauty'. The women who achieve super-model-like bodies and looks are the new post-socialist working heroines. To achieve that, they have to work hard and be dedicated. In my video, I take an ironic look at this new work, juxtaposing it with the soviet period working women's work.”

Now, more than twenty years later, cyberfeminism remains as crucial as ever. Emerging technologies have the potential to encroach on human rights in ways that are unique to the age of artificial intelligence and digital surveillance. But this can be avoided. In harnessing these technologies for advocacy and awareness, we can ensure a digital future that safeguards human rights.

Currently, Tralla is based in Edinburgh, where she works as an artist and human rights activist.