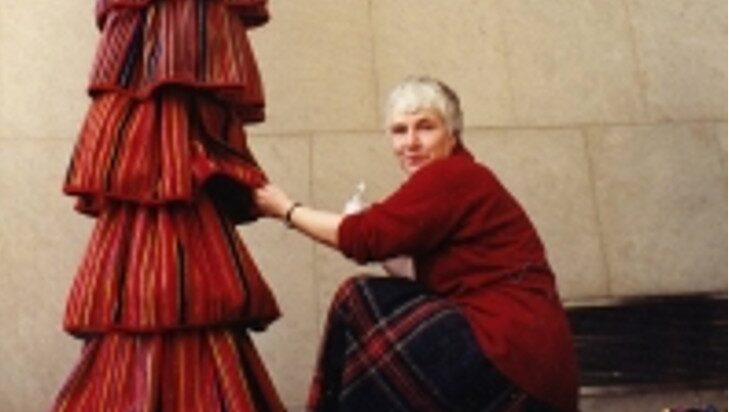

The artist that put it all together is Anu Raud, a master of textiles and Professor Emeritus of the Estonian Academy of Arts.

The artist's intention was to express the phenomenon of life being given by mothers down the generations. Each skirt overlaps the one below it, as the life of a mother overlaps and oversees the growth of her child before a subsequent life takes form. Akin to how a tree propagates and overlooks its saplings below it. This is actually a more suitable comparison than a tower, as the artwork is called Emapuu (“Mother Tree”).

Emapuu was gifted to the United Nations in 1995 by Raud and then President of Estonia Lennart Meri. As seen in Mark Soosaare's 2002 documentary Anu Raud – elumustrid (“Life Patterns”), the ceremony was an important celebration, as it marked a re-entry of Estonia into independent international discussions. The film is uplifting, showing the dichotomy of life on her farm in Estonia, framed side by side against her watching with pride as a crowd and photographers admire Emapuu.

Of course, it isn't the only art around in the Headquarters of the UN. Even the grey walls of the General Assembly Hall are the canvas for two murals by French cubist Fernand Léger. Art is everywhere.

Nigerian sculptor Ben Enwonwu's grand sculpture Anyanwu (“Sun”) shows a woman in the finest garments and jewellery of the Kingdom of Benin, which ruled in southern Nigeria from the 12th to the 19th century. She is six feet and ten inches tall, gazing below at passersby with a regal stance. This artwork was given in 1966.

Tunisia donated a mosaic from the 3rd century, which shows the rotating of seasons. The mosaic is from a time when Tunisia was a central point in the Roman Empire's flourishing Mediterranean trade network. Pheasants and four different crops can be seen around the square mosaic that would have been a floor originally. It summons the sensations of a sun-soaked, bountiful country and recalls the legacy of millions of gallons of olive oil making its way across the sea in ceramic amphorae centuries ago.

Then there's “Arrival” by John Behan. In the North Garden, the sculpture shows Irish immigrants stepping out from a crowded ship. Dense shadows bathe the planks of the ship and the quiet profiles of the passengers. The figures are walking towards a future in a new land, to whichever place circumstances brought them.

Each piece represents another realm of the human experience; and proposed donations, selected by the UN Cultural Activities Committee, exhibit many different ways of looking at all of these nations.

What warms my heart most about the collection is threefold. Firstly, its optimism. No matter what political changes sweep through nations, these pieces stand for a consistent right to be represented in the world. For a country to have a physical part of itself given space in the headquarters is to be at the democratic table of discussions.

Secondly, the art welcomes the individual identities of the international community. There are 195 member states represented in the United Nations, and yet, their individual cultural qualities are emphasized.

Thirdly, the presence of these creations in the UN Headquarters effuses a duty to act according to what will benefit the people represented by these works of art. Art represents humanity across borders.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.