There won't always be a manifesto to give us clear hints. For example, the Painters Eleven, Toronto's first group of abstract expressionist artists, said at their founding, “There is no manifesto here for the times, there is no jury but time. By now there is little harmony in the noticeable disagreement, but there is profound regard for the consequences of our complete freedom.” If there's no philosophy to work with, the meaning is another layer deeper.

How cultures perceive the principles of design and colour are one clue: a painting with pastel colours is content and unburdened, reds call for attention, and an abundance of blue is dreamy and free. Erratic, scratchy lines indicate agitation, straight lines indicate focus. Watch, then, for the deliberate use or neglect of design principles like symmetry, repetition, blank space, and contrast. It will show us what we are supposed to notice.

Alternatively, there's nothing stopping viewers from ignoring the non-representational intent of an abstract artwork and looking for recognizable beings, places, and objects. To do this is like using art as a Rorschach test that explains the innerworkings of our minds.

Consider Estonian-American painter Toomas Vink-Lainas' paintings and drawings, several of which are part of the Toronto Estonian Virtual Art Gallery (TEVAG) collection operated by Jaak Järve and Mai Vomm Järve.

Looking at what's listed as Vink 7 (painted in acrylic in a wide rectangular orientation) our eyes are guided from right to left. White outlined details and swift black lines all blow away from a warm orange glow on the right side of the painting. Blotches of red appear along the way to the washed out left side of the painting. To speculate about its meaning, think about what phenomena a loss of colour might stand for. The loss of heat and vegetation from autumn to winter ; exchanging safety for vulnerability. Think representationally, and you'll notice the structure of Earth from the inner core, where the paint is blended tenderly on the canvas, to the crust, or the diminishing number of lights of a city from downtown to the outskirts.

All of this is sensed from a shift in colour. As pioneering abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky (who, in 1896, almost became professor of jurisprudence at the University of Dorpat in Estonia) said “Colour is a power which directly influences the soul. Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”

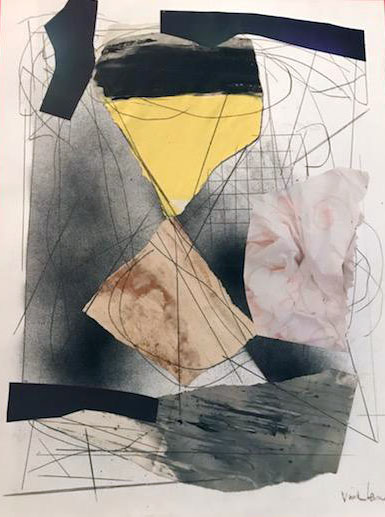

More shape and perspective-oriented is Vink-Lainas' mixed media drawing Vink 20 (24 x 18 inches). The most noticeable details here are the downward and upward pyramidal shapes at the centre of the drawing and the grid in between, drawn with thin strokes. All of the thin lines in this piece chaotically float around the prominent shapes in the centre. However, Vink-Lainas, having worked his whole career as a graphic artist, deftly placed the thin grid at just the right angle, so that all of the chaotic lines appear to originate from this grid. It's as though we're looking at objects falling into an abyss down a metal storm drain.

The next time you go to a gallery and appraise an abstract artwork, step back, then stand closer, consider the techniques used, how it interacts with your eyes and thoughts, and ponder what the artist is telling you. Whether we love or loathe a work of art, it's worth being able to understand its purpose.

Written by Vincent Teetsov, Toronto