So all that remains for me is to look back and think how I got here. There is enough to be satisfied with: my peasant ancestors became merchants, which led to me having the education that allowed me to work on the team that developed the International Space Station. How cool is that?

Who helped me set my goals and who set me on the path? Of course, my parents deserve most of the credit. But besides them who? It had to be teachers, but teachers in the broader sense of anyone who imparted knowledge to me whether or not she or he had a teaching certificate.

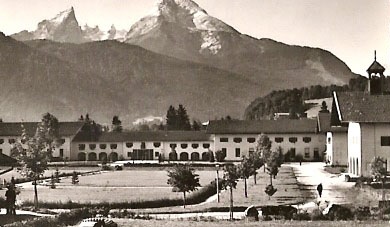

With most teachers the relationship lasted but a short season or a year, and in most cases was very one sided. I doubt if they ever remembered my name after the class and I barely remember theirs. But there are exceptions. Foremost in my mind is the teacher I had in a Displace Persons' (DP) camp: Mrs. Heleena Koppermann. In 1945 refugees from East Europe in Germany could not return home, but the German economy was in shambles and Germany no longer needed us. The American Military gave us an opportunity to find accommodations in camps in which we were fed. My parents and I moved to a camp named Insula, situated in former army barracks complex near Berchtesgaden, Bavaria. There, among the Poles and Latvians who made up the majority of the camp, were about 60 Estonians, including three grade-school-aged children. I was one of them, a fourth grader.

The Estonians were concentrated on one floor of a barrack. The rooms had double-decker beds, and two families were assigned to a room. In time Mr. Andre fashioned dividers between the families out of Masonite (pressed wood) salvaged from crates. So the Estonian community of the camp became a very close “family” with little privacy and thus few secretes from each other. Of course there were irritations that come with such closeness, but also friendships. We were fed meals from a communal kitchen supplied by the American Army but administrated by the camp inhabitants. Given that the Poles and Latvians did not trust each other, many of the camp administrative posts were given to the smallest minority, the Estonians. But of course each nationality had its own school.

Upon urging from a larger Estonian center three volunteers were found to take on the chore of educating us: Mrs. Heleena Koppermann, Miss Hilda Laas, and Mr. Fritz Andre. They had no children themselves and had no teaching experience. They received mimeographed materials from larger Estonian centers, found an empty room in the barracks' basement and commenced teaching. The problem with being in such a small school was that there was no chance of getting away with not doing homework assignments. Mrs. Koppermann took on Estonian literature and related topics, Miss Laas Geography and similar, while Mr. Andre taught me woodworking for just half a year, using tools in the camp workshop. In the other half of the year Miss Laas taught us how to knit. An old sweater was unraveled and knitting needles borrowed and so together with the two girls I learned knitting. No problem, I was secure enough in my manhood to endure that. Though I have never used my knitting skill since then, it taught me that I can learn even unexpected tasks!

Mrs. Koppermann was the soul of our school; she was a fiery, energetic young lady with piercing brown eyes. I was drawn to her. As a 12-year old I most likely was in love with her. What I remember most of what I learned from her was what happened on one occasion outside the class room. I had loved to brag of how I hated Russians who were the cause for us having to flee Estonia. I used to repeat, “Give me a Russian and I will wring his or her neck unless it is a very young girl.” Mrs. Koppermann heard me during one such tirade. She pulled me aside and asked me, “Arved, did you know that both my parents came from czarist Russia during the First World War, and thus I am an ethnic Russian?” I was devastated. And lesson was learned. I never bragged like that again.

In an earlier incident when we were still in Tallinn, a teacher saved me and my parents from getting into serious trouble. In 1940 I was in my first year of school. The Soviet Union had just claimed Estonia for itself, and the country was in a rapid transition. The flying of the Estonian blue-black-white flag was forbidden. On the front wall of the classroom hung a picture of Stalin in place of our deposed president Päts. My grade school was part of the seminary that allowed teachers in training to practice their skills. One day a student teacher handed out a mandarin to each student. Next the teacher told us that Stalin loved children and understood us because he himself was trained to be a teacher and thus sent us these mandarins. We were now told to write an essay thanking Stalin. I do not remember what I wrote but I remember that I drew Estonian flags around it. After I handed in my richly illustrated essay, the teacher came to my desk, and whispered in her squeaky voice that the illustrations were not allowed and I should take the essay to my parents. All I remember of her is her weird voice. At home my father subsequently kept his blue-black-white table flag mounted on “Pikk Herman” in a locked desk drawer. Who knows what trouble this teacher kept my parents from by not informing the authorities, as she was required to do?

Some learning experiences were negative. Perhaps the earliest that I remember was when I was six years old and our maid was tasked with making me practice reading in preparation for an entrance exam for grade school. To enter we had to be able to read. It was the word “but” which challenged me. In Estonian it is “aga.” The maid told me “read it!” And I would read “a-ge-a.” This went on until I was in tears, but I held my ground. Subsequently I mastered reading and passed the exam.

(to be continued)

Arved Plaks, January 2013