As you walk back to your dwelling one evening, the sky turns blindingly bright, as if night reversed back into day. An object in the sky, consumed by flames, breaks into nine separate pieces and crashes to the surface in an explosion.

The estimated age of this meteorite impact varies significantly, with the most common estimates falling between 3,400 and 4,000 years old. For Bronze Age Estonians living on Saaremaa, the entrance of this extra-terrestrial matter into their domain would have been the brightest, loudest, most unexpected event of their living memories. Atlas Obscura has positioned the impact as “the last giant meteorite impact to occur in a densely populated region.” The force of the meteorite is frequently compared to the force of “a small atomic bomb”, which would have resulted in many casualties.

The impact crater lake that formed within Kaali kraater is 110 metres wide and up to 22 metres deep. While Kaali kraater, the biggest impact point, or the eight accompanying craters that form the crater field, are in reality nowhere near to being the biggest meteorite impacts in the world, they are nonetheless a strong example of the symbolic allure of meteorites.

After that big day, Kaali järv, the impact crater lake of Kaali kraater, became a place of significance. People have lived on Saaremaa for at least 7,000 years, and the main crater of this crater field became a meeting place for locals not long after the meteorite struck. Archaeological excavations in 1978 revealed a stone wall that protected a settlement at the crater, revealing a human presence at the crater between 2,200 and 2,700 years ago. Meanwhile, research conducted in 2004 between Tallinn University of Technology, the University of Tartu, and Uppsala University indicated that the site was “primarily ceremonial.” The study also suggests that three separate legends may have been inspired by the event: the flight of the god Taara from northeast Estonia to Saaremaa, a song in the Finnish epic Kalevala that tells a story of the sun falling into a lake, and northern Estonian folk songs that “describe the burning of the island of Saaremaa.”

Obstructions in the water of Kaali järv have prevented further discovery of artifacts, but previously discovered remains of animal sacrifices, some dated to as late as the 1600s, suggest an enduring, fervent belief in the spiritual significance of the crater. Among scientists, conclusive proof of the crater being caused by a meteorite was found in 1937 with the discovery of meteorite-specific iron debris, after extensive field work at the site.

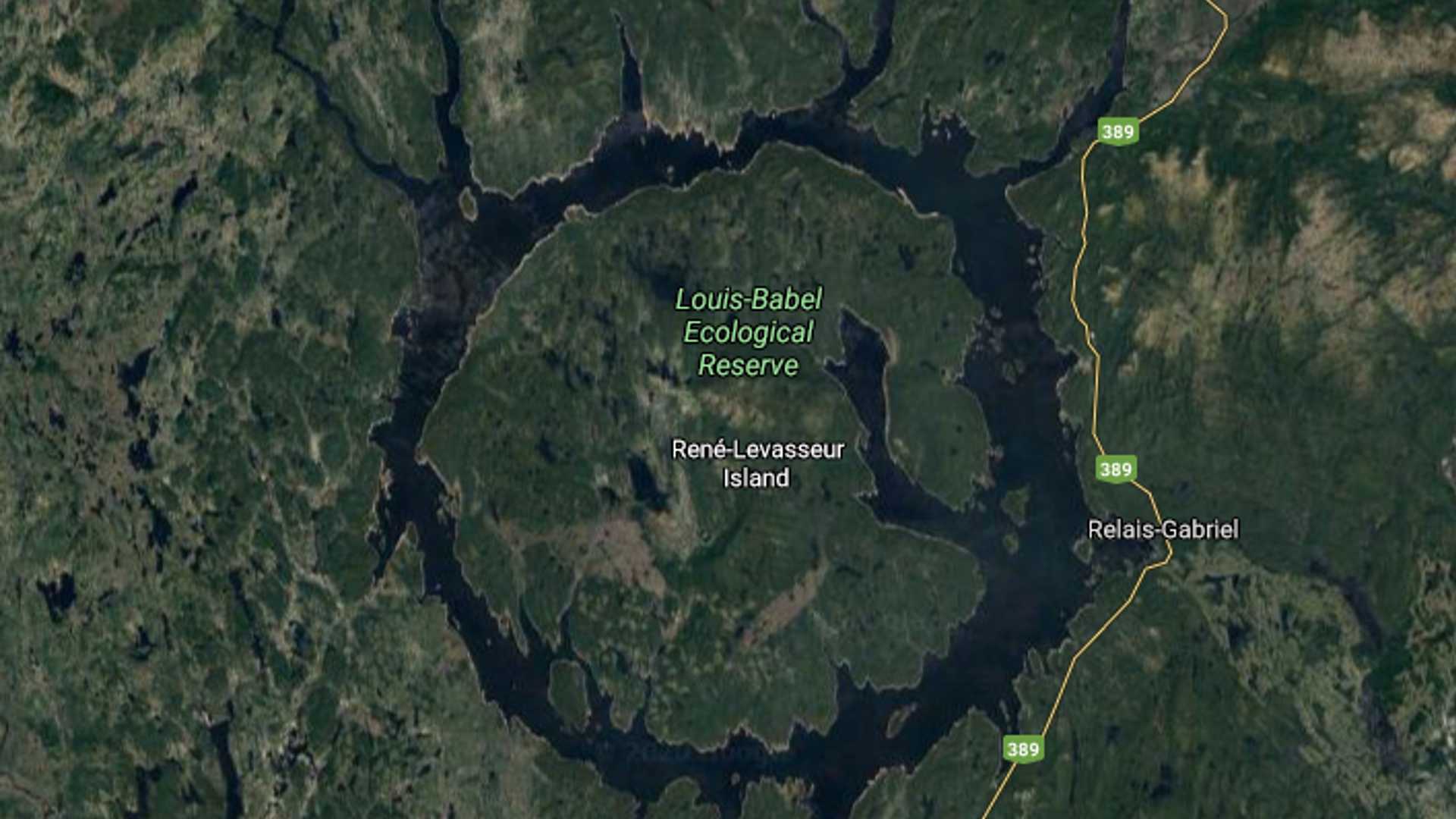

Befitting the vast natural landscape of sparse, rolling hills and coniferous trees, Manicouagan crater in the province of Québec is among the top 10 largest meteorite impacts in the world. The crater is 350 metres deep (as a comparison, the Fairmont Royal York hotel in Toronto is 134 metres tall). 214 million years ago, the crater was formed by a meteorite, creating a dent in the earth that is currently 72 kilometres wide. The crater is much older, deeper, and wider than Kaali kraater.

This curiosity was enough to fuel bizarre myths about canoers getting badly disoriented by their location and coming to believe that the earth was changing its rotation relative to the sun.

Big or small, though, these natural features continue to inspire daring and sometimes physically taxing pursuits. For example, in the summer of 2019, 14 young Canadians who had recently fought cancer joined together for a restorative canoe trip around the crater's lake, Lac Manicouagan (Lake Manicouagan).

Just as the Kaali meteorite found its way into folk legends, the Manicouagan crater and the water surrounding it have created stories, trepidation, and curiosity among the adventure sport community and wilderness travel enthusiasts. This curiosity was enough to fuel bizarre myths about canoers getting badly disoriented by their location and coming to believe that the earth was changing its rotation relative to the sun.

Then, the crater and its adjacent features have also been harnessed for engineering purposes. Within the crater is Manicouagan Reservoir, created by the construction of the Daniel-Johnson Dam, started in 1959 by Hydro Quebéc. Previously, two separate lakes strafed the edge of the crater. The reservoir contains one of the highest ratios of island to lake with René-Levasseur Island, that sits in the middle of the impact lake. This reservoir, together with the Manicouagan River, is what powers several electricity-generating stations.

Despite being reminded of our minute scale compared to these massive impressions in the earth and the astronomical events that cause them, we wander close, investigating the scene. We might even build a structure of our own beside it, to harness the elements as much as we can. It's the best we can do to address our awe concerning these colossal phenomena.

This article was written by Vincent Teetsov as part of the Local Journalism Initiative.