We have an incredible amount of faith in our ability, as a collective, to keep our country safe and free and to keep up with or even surpass many other countries. As individuals, we also believe in our own ability to succeed in life. We are very resilient and not afraid of hard work.

Religious faith, however, plays a very small role in Estonian society. I grew up in the 1990s, in the aftermath of the Soviet occupation, where all religious practice was heavily restricted. I didn’t learn or hear much about religion in my family or at school. When I was around five years old, I became best friends with a girl whose family was highly religious, and it made me curious to know what it was all about. So, I joined my friend at Sunday school once or twice just to see for myself. But for some reason, it wasn’t for me.

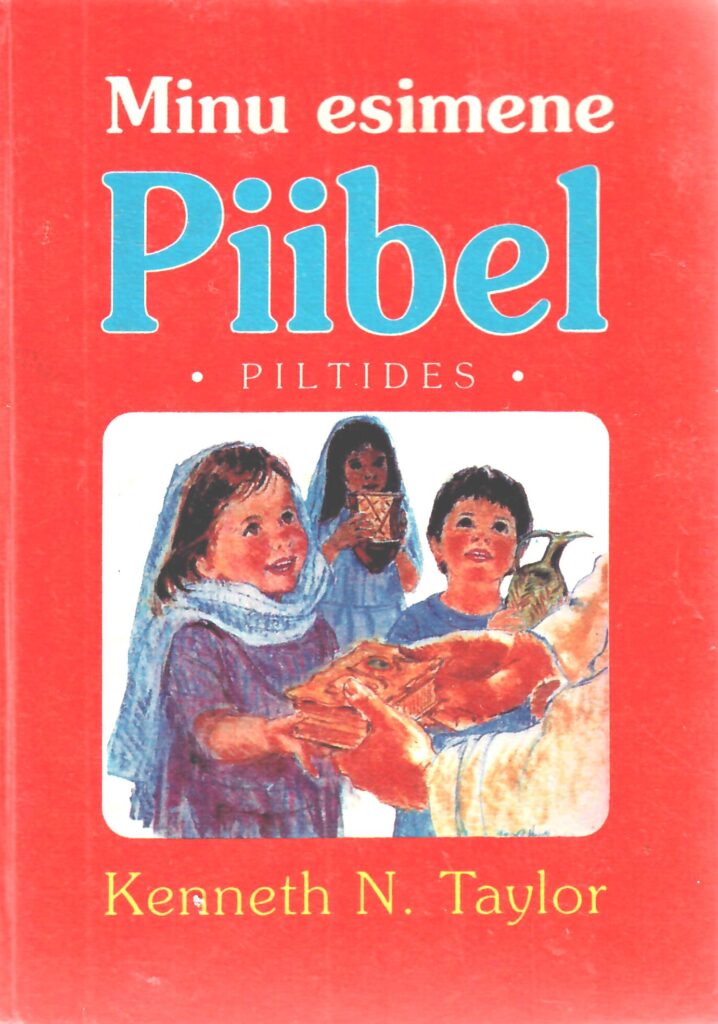

My mother, noticing my curiosity, bought me a small, colourful Bible full of illustrations for children. I’m pretty sure I read through the entire book, and I remember keeping it for a long time. It was a beautiful little book, and at the very least, it gave me a vague idea of what the Bible was about.

At school, we learned that the Crusaders forced the Estonian people to convert to Christianity in the thirteenth century and that the historically pagan Estonians resisted as much as they could.

Non-Estonians often ask me if our lack of religious belief is solely because we were under the communist regime for so long, where religion was not accepted. But the truth is that the Estonian people have always been a rather questioning nation. We tend to be suspicious of things, which makes it hard to convince us to believe in something.

What she did talk about a lot was nature. She would always tell me to speak to the plants, to ask for permission before picking a flower, and to apologize if I accidentally harmed a plant.

That said, some Estonians have been convinced. For example, the family I mentioned earlier, as well as my grandmother, have religious connections. My grandmother once told me that her grandmother was religious and that they used to attend church in secrecy during the Soviet occupation. My grandmother is even baptized (conversely, I’m not). However, I don’t recall her ever talking about religion, God, or church when I was growing up. What she did talk about a lot was nature. She would always tell me to speak to the plants, to ask for permission before picking a flower, and to apologize if I accidentally harmed a plant.

The belief that everything in nature is sacred and inhabited by spirits is much older than Christianity. This connection to nature-based spirituality has accompanied Estonians throughout history and continues to play a central role in our belief system today.

Aside from that, Estonians are also quite superstitious and always have been. Some superstitions I can remember include: if you serve a piece of cake to someone and it falls on its side, you won’t get married; opening an umbrella indoors brings bad luck; if you drop a fork on the floor, expect a surprise visit from a woman; if you drop a knife, expect a man.

We have many of these superstitions, and some of them exist in other countries as well. I don’t think most people take them very seriously, but some follow them “just in case.” For example, I try to avoid opening an umbrella indoors, but my day won’t be ruined if I accidentally do it.

Most Estonians I know are either atheist, agnostic, or spiritual. By “spiritual,” I mean they reject organized religion but believe in some form of higher power or simply in Mother Nature. It’s hard to define because Estonian beliefs are very individual and deeply private, varying greatly from person to person.

Perhaps religion is more accepted in community-oriented countries, like Brazil, where people love gatherings and being part of a group. Estonians, on the other hand, enjoy solitude a little too much.

When saying goodbye, they often say things like “Fique com Deus” (“Stay with God”), and at first, I had no idea how to respond to that.

I moved to Brazil over ten years ago, and it was quite a culture shock for me as religion plays a central role here. In everyday conversations, Brazilians frequently reference the Bible. When saying goodbye, they often say things like “Fique com Deus” (“Stay with God”), and at first, I had no idea how to respond to that.

There are also so many different religions in Brazil—Catholicism, Evangelical Christianity, Spiritism, Afro-Brazilian religions, and more—each with their own beliefs. Sometimes, politics and religion get mixed together, and it can even be difficult to find a school that is not influenced by a religion.

My Brazilian husband is somewhere between agnostic and atheist, but like almost all Brazilians, he was baptized. He once told me that one of the best things about belonging to a religion is the sense of community—the ability to come together and have a support system around you—and for that reason alone he would consider going to church.

Estonian society, however, is too individualistic to embrace a collective way of living, so I believe Estonia will remain a non-religious country for the foreseeable future. That said, we do come together when it matters most, whether it’s to protect our country or to sing together at Laulupidu (the Estonian Song Festival), held every five years.

If you’d like to learn more about religion in Estonia, I invite you to watch my video titled “Religião na Europa vs no Brasil” (“Religion in Europe vs. Brazil”) on my YouTube channel. You can turn on YouTube’s translated captions in English to follow along.