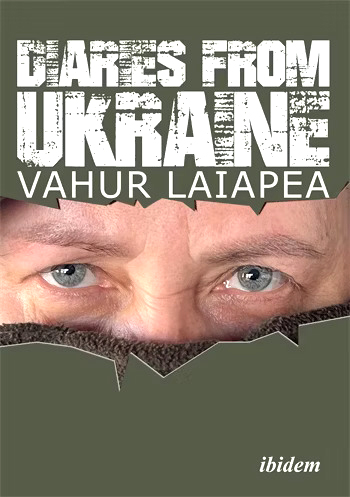

Diaries from Ukraine is a new book, published in February 2025 by ibidem Press. Written by Vahur Laiapea., it has been translated by Ott Palumäe and Tiiu Palumäe. The 152-page book is available on Amazon.

The legend of the Holy Grail speaks of a paraplegic king. Parzifal did not ask a single question about the procession that was passing him. Nor did he ask about the woman carrying a vessel at the front of the procession. He saw but didn’t ask. And because he failed to ask, women could not give birth, trees couldn’t bear fruit, cows didn’t give milk and the king became paralyzed. All because he had been taught to politely remain silent.

According to Russian writer Artur Solomonov, a priest from St. Petersburg has been arrested for claiming that Russian soldiers who die in Ukraine will not go straight to heaven. The paragraph under which he was charged deals with spreading false information about the army.

There can be various reasons for remaining silent. Comfort. Fear. Malice. Maybe it doesn’t affect me. Maybe it will pass. Maybe someone else will deal with it. It will affect us sooner or later. It won’t pass if we don’t intervene.

A people whose chosen leaders have thoroughly trained them to hate us, prepared them to destroy us. Among them there are undoubtedly people who do not wish for this. But most of them remain silent.

We live in the vicinity of Russia, which is attacking Ukraine. We could be next. Or the ones after the next ones. It makes no difference. Our neighbours are a people who have lost their moral compass. A people whose chosen leaders have thoroughly trained them to hate us, prepared them to destroy us. Among them there are undoubtedly people who do not wish for this. But most of them remain silent.

Maybe it will pass?

The texts in this book are written in Ukraine and Estonia between May 2022 and June 2023. In my written accounts I have tried to give a face to the people who continue to be ravaged by this hideous war.

Vahur Laiapea is an Estonian documentary filmmaker and writer. He has visited Ukraine on numerous occasions during the ongoing war.

Deaths of Volunteers in Soledar

Andrew Bagshaw and Chris Parry lost their lives in Soledar on January 6th, 2023. They had driven there to evacuate an elderly woman.

They were actually on their way to Bakhmut when they received a request from volunteers working in Kramatorsk to pick up the elderly lady. Bakhmut had to wait. The men changed course and headed towards Soledar.

Andrew was a talented and renowned geneticist (forty-seven-year-old) from New Zealand who had been living in England before coming to Ukraine. Twenty-eight-year-old Chris was a running coach from England.

He arrived in Ukraine on March 5th, 2022.

In Kramatorsk, I meet Olga. She’s a volunteer who has, along with these men, saved hundreds and hundreds of people from the war. Olga met Andrew in July of the previous year. They didn’t share a common language. Olga doesn’t speak English. Andrew could speak neither Russian nor Ukrainian. They communicated with the help of Google Translate. Upon speaking into your phone, the app generates a written translation that appears on the other person’s screen.

Their first joint trip to Bakhmut was to evacuate people from the war. Olga suspects that Andrew could be a Russian spy. He entered strange sequences of numbers and letters into his laptop. Olga believed it was coded text. Olga’s big question: WHY did this man come to Ukraine? How is this his war? “I couldn’t comprehend it. I couldn’t understand what brought this person here,” says Olga. “Would I go to a foreign country if there was a war there? No, probably not.”

And how strangely and reservedly Andrew behaves. He doesn’t express his emotions. When mines explode, Olga screams and drops to the ground, while Andrew barely nods his head.

For about a week, Olga suspects that Andrew could be a Russian spy. Then she found out that he is a geneticist. The marked sequences he manipulates with on his computer, are tools for his research.

I Google Andrew’s research topics. I realise that I don’t understand any of it. But I’ll paste here a couple of sentences with keywords from Wikipedia. It indeed resembles coded text: a sequence consisting of two nucleotides is called a dinucleotide microsatellite (e.g., ACACACACA). A repeated sequence consisting of three nucleotides is called a trinucleotide repeat sequence (e.g., AGCAGCAGCAGC).

Andrew treated people with the utmost respect. “He even showed respect for alcoholics,” marvels Olga. “And he stayed by the bedside of a sick elderly person, holding their hand until the medics arrived. In Bakhmut, he revisited the children he had previously helped. He loved them deeply.” Andrew seemed lonely. Aleksander, my reliable fixer, suggested to Olga in the autumn that she integrate foreign volunteers into one team so that they could communicate with one another.

Andrew was joined by Chris, a volunteer running coach.

Olga noticed that Andrew wasn’t eating properly. He often had nothing in his fridge. Olga started bringing food to Andrew. Brought it to him herself, sometimes asking her husband to deliver it. Her husband had to tell Andrew that Olga would be offended if he didn’t accept the food. Andrew accepted it.

Evenings were the time to make plans for the next day. Comprehensive work with information–discerning where it was safe to travel in a city under bombardment and where the risk was too high. This information was constantly updated.

On December 24th of the previous year, Olga had to leave Kramatorsk.

Her mother, who lived in Poltava, had suddenly fallen seriously ill. Olga drove to the hospital where her mother had been taken. Olga saw Andrew for the last time on December 24th. After some time had passed, Olga’s husband, who was serving in the military, was wounded.

“We taught Andrew how to hug,” says Olga. “We hug a lot here. He got used to us hugging him, but he never initiated it. But when I told him that my mother was seriously ill, he hugged me first!”

On January 6th, contact was lost with Andrew and Chris. Communication was lost, hope persisted. Maybe the men were still alive. Taken captive? Wagner mercenaries were fighting under Bakhmut.

They had a fixed price list that motivated them to keep captured foreigners alive. They were paid $7,000 for every living foreigner.

For a dead foreigner with identification, the payout was $500. For unidentified foreigners without documents, they received nothing.

Andrew continued to carry out evacuation trips to Bakhmut. Even to areas where it was strictly forbidden to go. Areas on the other side of the river, where the risk of death had grown extremely high.

The Russians offered the Ukrainian side a silent night for Orthodox Christmas, from January 6th – 7th. Olga hoped it would work. That it would make Andrew’s trips safer. On January 5th, Olga scolded Andrew on Viber. Andrew had once again evacuated people from that area.

Here are excerpts from Olga and Andrew’s last correspondence:

O: It’s a trap! You can’t go! Foreign troops are already there.

O: I’m sorry, Andrew. It’s a deception. There aren’t any people living there. That address is far beyond the river.

A: There are still many people living on the east side of the river. I’ve been there many times in the past two weeks. I will find the exact location. It could be safe there. If it’s further east, then infantry battles are taking place there. If so, it’s not wise to go there.

… a volunteer named Philip remotely manages information about people in need and tries to send rescuers to them. It’s a kind of dispatcher’s work in its own right.

O: I already saw where it is! There aren’t any living civilians there. The army’s there. It’s a bad address. I’ve already deleted it.

The conversation goes on for a long time. Olga tries to convince Andrew to give up reckless risks. The conversation also addresses cases where people who have asked for help often refused to leave their homes (read: basements). There were and are many such cases.

And we’ve made it back to January 6th, when communication with Andrew and Chris is lost. Andrew and Chris, who are already on their way to Bakhmut, receive information from Kyiv. There, a volunteer named Philip remotely manages information about people in need and tries to send rescuers to them. It’s a kind of dispatcher’s work in its own right. Philip asks Andrew and Chris to go to Soledar to evacuate an elderly lady. Communication with the men is lost.

On January 8th, Olga calls Andrew’s phone. It rings. Nobody answers. Olga speculates that it’s already in the hands of the Wagner Group.

Volunteers and the police begin to investigate to determine the fate of the men. A few days later, information is received from the Wagner militants that the men’s bodies have been found.

The bodies are handed over to the Ukrainian side. They are presumably exchanged for dead Russian soldiers. The Russians have taken care of the foreign volunteers’ bodies. They’ve been washed clean of blood, placed in black bags and in proper coffins, covered with red cloth.

On January 20th, Andrew and Chris’ bodies arrive at the morgue in Kyiv. Olga still has hope. Hoping that there’s been a mistake and that the bodies handed over aren’t Andrew and Chris. Daniel, a volunteer from Kyiv who took the bodies to the morgue, gets a chance to identify them. He calls Olga. Yes, they are indeed Andrew and Chris.