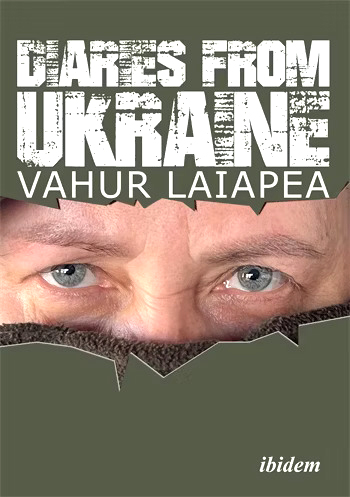

Diaries from Ukraine is a new book, published in February 2025 by ibidem Press. Written by Vahur Laiapea., it has been translated by Ott Palumäe and Tiiu Palumäe. The 152-page book is available on Amazon.

The Long Road to Becoming a Woman

This brave woman was born a boy. I don’t know how she was baptised after she was born. I talk to Oksana on the phone for an hour.

From her Facebook pictures, she looks like a nice young woman.

Very many transgender people have contemplated, attempted, or died by suicide. Oksana attempted suicide in 2012. She survived. She started preparing for a sex change. Underwent long-term hormone therapy. Oksana’s gender reassignment surgery at the hospital in Zaporizhzhia was planned right for the beginning of the war. It was cancelled. Postponed. Oksana went to war on the second day of that war.

Oksana was born and raised in Donbas, in the city of Makiivka which conurbated with Donetsk. In 2014, she fled her hometown. She was targeted, picked up at her home soon after she left. A close relative, a cousin, complained to the new authorities about Oksana.

A lumpen, an alcoholic, a separatist. This is how Oksana describes her cousin—a traitor who later died a traitor’s death.

Oksana joined the defenders of Ukraine as a volunteer in 2014, defending Donetsk airfield.

Do you remember the first person you killed? Oksana doesn’t like the word “kill.” “We “‘utilise’ enemies,” she says. “He was a separyonok, a little separatist. I took his automatic rifle. I fought for a month and a half with that weapon.”

In the early morning of February 24th, 2022, Oksana hears explosions from her apartment in Kyiv. On the fourth day of the war, she is given a gun.

Oksana doesn’t want to talk about combat. She talks about massive, chronic fatigue and emotional burnout. And knowing you can’t leave. Behind you, in the rear, are your own.

Oksana talks about an intercepted radio transmission where the Russians use the expression grazhdanskih obnulitj. That means eradicating civilians, murdering them. And eradicate they did.

Protecting Majorski, a town near Horlivka in Donbas, Russian forces encircle the settlement. The defenders manage to break the siege. Eighteen civilians in the settlement are murdered by the Russians. Oksana talks about an intercepted radio transmission where the Russians use the expression grazhdanskih obnulitj. That means eradicating civilians, murdering them. And eradicate they did.

The last few weeks have been very difficult. The army unit is fighting near Bakhmut. The company that Oksana began fighting under consisted of 120 fighters. Only a third of them are at the lines now. Twelve fighters were killed last week, two more this week.

Oksana tells of a recent Russian landing operation in which the six of them fought a battle against a unit several times larger than their size. “We took 300,” she says. Meaning, the wounded were not left behind, they were taken along.

I call Oksana at the agreed upon time, she’s busy. I’m training young boys, she says. I called back later. Who are they? Freshly mobilised, five boys. I taught them how to shoot from different positions.

How do soldiers behave after their first battle? So many fall into a stupor. Then a couple of slaps and 200 grams of vodka will help. Not everyone can kill. Some people start running when they should instead be lying down. Ten thousand shots need to be fired before you can consider yourself an experienced soldier.

War directly exposes the substance of an individual, says Oksana. Shows you who’s a real human being. In October, when we were defending Horlivka, we brought two wounded soldiers out of the line of fire. I met one of them when on vacation at the end of December. We hugged. We didn’t talk about the rescue. There were six of us rescuers—we couldn’t have done it alone.

On October 30th of last year, Oksana was wounded. A shrapnel wound to the leg. She was treated at Pavlohrad Hospital. She met an Estonian who was also being treated there—Toomas. Hemingway was once said to have met at least one Estonian at every port (or port tavern?). There are probably more Estonians helping Ukraine now than we can imagine.

She also says that she can tell from someone’s eyes whether they’ve already been on the front lines. The gaze of these people is different. Death has looked them straight in the eyes.

Have you taken anyone prisoner? No. We don’t take prisoners. But you yourself—would you surrender? No. I always have a grenade with me. Let’s call it a good luck grenade. I don’t want to get tortured. That’s what Oksana says.

She also says that she can tell from someone’s eyes whether they’ve already been on the front lines. The gaze of these people is different. Death has looked them straight in the eyes.

Alina, her partner, waits for Oksana at their Kyiv home. When the war is over, Oksana will start hormone therapy again. It can’t be continued right now—too much of a strain on the body. After the war is over, the brave Oksana can finally reach the end of her long road to becoming a woman.

Vahur Laiapea is an Estonian documentary filmmaker and writer. He has visited Ukraine on numerous occasions during the ongoing war.