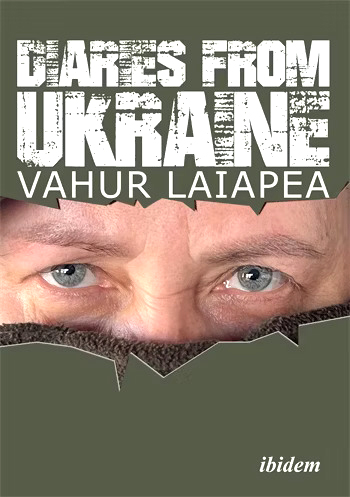

Diaries from Ukraine is a new book, published in February 2025 by ibidem Press. Written by Vahur Laiapea, it has been translated by Ott Palumäe and Tiiu Palumäe. The 152-page book is available on Amazon.

Auntie Lehte from Popilnia Village

I was four or five years old when I got to feed calves with milk. I believed I was doing it as a job. I was paid three roubles for it. Those were my first earnings and feeding calves was my first job. I watched a pig being castrated. I was scared of an angry rooster outside who jumped on top of my head a couple of times. I gave a piece of sugar to a horse from the palm of my hand. I tugged on a cow’s udder, hoping that milk would start to trickle. It didn’t. I buried the base of an old copper-coloured petroleum lamp in the sand. It’s my hidden treasure, waiting to be dug out after fifty years.

The mean rooster ended up in a soup pot. I stuck one of his feathers in my hair and I became a Native American. The “last Mohican,” of course. I had a bow. During those summers I felt fully alive, as children do.

All of this happened at aunt Lehte’s place in Nõva, Estonia. Aunt Lehte had a husband but didn’t have any children. I probably filled a gap in her longing for a child. For the sake of simplicity, I call her Aunt Lehte. Lehte is technically my cousin.

Aunt Lehte grew up as an orphan. On June 25th, 1941, the forest brothers in Võru County shot her father, who had gone along with the Soviet occupation. It had been less than two weeks since the brutal day of the June deportation when tens of thousands of people from Estonia were deported to Siberia and sent to the Gulags.

Lehte had just turned four a couple of days before her father’s death. In 1946, her mother died after being hit by a car.

I don’t know exactly how or where it ignited, but Lehte’s love for Aleksander took her to Ukraine. My childhood summers in Nõva came to an end.

The August storm of 1967 brought down trees and bent the fate of people. A significant number of Ukrainians came to Estonia to work in the storm-damaged forests. Among them was a young, hot-blooded man named Aleksander. I don’t know exactly how or where it ignited, but Lehte’s love for Aleksander took her to Ukraine. My childhood summers in Nõva came to an end.

Years became decades. I knew that somewhere far away in Ukraine, in the Zhytomyr Oblast, Aunt Lehte was living her life. How she was living it, I did not know.

This time I drove to Ukraine with my own car. I reached the Zhytomyr Oblast two days ago. I called someone in Estonia who I thought might know more about the fate of aunt Lehte. I got the name of the village—Popilnia. I also learned that Lehte had passed away in 2019. I already knew that Lehte had an adopted daughter named Ilona.

I was dodging potholes for two hours to reach the village. It’s a large village. I started at the village council. Maybe somebody there would know someone who might have known Lehte.

I meet with the secretary of the village council. I’m so and so, inquiring about Lehte.

Lehte—the midwife?

Yes, she also worked as a medic in Estonia. But she’s dead…

Dead? No, Lehte is alive. If you go past the church, take the second street across the road. The first two-story house. That’s where she lives with her daughter and her daughter’s husband. Yes, Lehte’s husband Aleksander died already back in 2003.

Mykhailo, Lehte’s son-in-law, arrives. I follow him in my car.

We enter the house. Mykhailo opens the door to one of the rooms. In bed lies a petite elderly woman. It’s 85-year-old Lehte, who I remember as a very young woman. I sit down beside her.

Hello, Lehte! I am Vahur.

There’s a glimmer of recognition in Lehte’s eyes. She replies in fluent Estonian, without an accent.

We talk. Lehte sometimes switches to speaking in Russian. She speaks softly and intermittently.

I don’t understand all of it. But she is cognisant, she understands and remembers.

“My homeland is Estonia”, says Lehte. Her eyes fill with tears.

“Do you want to be buried in Estonia?” I ask.

Yes. Lehte wants to be buried in the Pindi cemetery—in the family burial plot where her father, mother, and grandmother rest. My mother as well.

Lehte started taking care of the abandoned baby. The newborn remained in the maternity hospital for seven months before Lehte could bring her home.

Ilona arrives, Lehte’s forty-three-year-old daughter. We talk to her about the fact that Lehte is not her biological mother. Ilona’s biological mother, being a young, eighteen-year-old woman, abandoned her in the maternity hospital right after her birth. Lehte started taking care of the abandoned baby. The newborn remained in the maternity hospital for seven months before Lehte could bring her home.

I go to Lehte once more. I tell her that she is a very dear and important person to me. Those summers spent at her home in Nõva are still with me. I ask Ilona to take a photo of us. I leave. I feel I have finally closed a chapter that had been unresolved for over fifty years. I got to thank Lehte and say goodbye.

Vahur Laiapea is an Estonian documentary filmmaker and writer. He has visited Ukraine on numerous occasions during the ongoing war.